CHF’s Director of Communications, Penelope Thomas, sat down with UK art historian, critic, and author Ruth Millington to discuss her new book: MUSE: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces. In this engaging work, Millington destabilizes some of the romantic, gendered notions of the portrait-sitter as the passive inspiration for great artists. In doing so, Millington sets the stage for a dialogue about artists’ real working lives and relationships, and reveals the hidden-in-plain-sight stories behind iconic works of art.

Penelope Thomas: What brought you to this subject matter?

Ruth Millington: I studied Liberal Arts—including English, Classics, and Art History—at university, so have always been interested in storytelling, as well as visual narratives. At its heart, Muse is a book of stories, and stories that all prove that fact really is stranger than fiction!

Just before I wrote the book proposal, I had been working on various features about the real-life figures in famous portraits. We all know the face of the Mona Lisa, but who was she, or he (as I was to discover), really? Who were the men in Hockney’s sunlit swimming pools? Was there a real “Weeping Woman” in Picasso’s life? These were questions I was asking and attempting to answer.

When it came to writing up the first of these features, the editor removed the word “muse,” replacing it with “art world legend” instead. A few months later, I worked on another piece, and this time was asked not to use the word “muse.” Of course, this all got me thinking about the term.

Of course, I recognised the problem with the label. Today, our perception of the muse is that of a passive, powerless female model, at the mercy of an influential and older male artist. Just think of Tracy Chevalier’s book, turned into a film, Girl with a Pearl Earring, in which the submissive maid-turned-muse serves Vermeer.

But, my research was showing me a different story entirely.

To start off with, I knew from studying Classics that originally the muses (there were nine of them) were divine goddesses. In Ancient Greece, poets, artists, and musicians would not only revere but invoke them, in order to be given inspiration for their songs, poems, and artworks. The muses had a position of power over mere mortals.

Likewise, throughout history, muses have inspired artists, and in more ways than you might first imagine. For a start, not all muses have been models. In fact, far from posing silently, muses have brought more to the role than external beauty. Some have sought the status of muse, others have inspired entire movements. Many muses have been artists, bringing creativity to the position and directly influencing an artist’s style—Klimt’s paintings of women in decorative dresses prove the lasting influence of designer Emilie Flöge.

And so, I realised that this trope of the muse as a passive romantic partner was, in fact, a myth, constructed for the sake of the great male artist.

The feminist in me knew I had to write Muse and reclaim the term for a truer account of art history to exist.

PT: How did you decide which artists you would feature? We don’t often have the chance to see Grace Jones and Marina Abramović discussed in the same book!

RM: I started with a long list, and I mean long! The more research I undertook, the more incredible muses I found.

Through my research, I realised that I could group the muses into specific sections in the book, from artists as muses, to performing muses and those whose presence carried political messages. Defining seven key themes helped me to identify who would be featured in the book.

I also wanted to shake up traditional narratives about the muse: everyone knows Cindy Sherman has taken herself as a muse, but what about Sunil Gupta? It was important to show that men, too, can be muses, as can trans people and non-binary figures.

But I didn’t make the final decision on who to include on my own: my brilliant editor Mireille Harper worked with me to curate a diverse list of muses, past and present, across cultures, genders, and races, whose stories were varied enough while all sharing the same thread: that they had been active agents in the making of masterpieces.

PT: The introductory blurb for the book on Amazon includes the sentence: “Muses have brought emotional support, intellectual energy, career-changing creativity, and practical help to artists.” Because The Clark Hulings Foundation is focused on business skills for working artists, this caught my eye! Could you give us a preview of some of the artist-muse relationships in your book that qualify as “practical help,” where the muse functioned as a business manager, an art dealer, a marketing assistant, etc.?

RM: Many, many muses have offered practical help to artists—artworks are material objects, which in the digital age I think we can often overlook or even forget at times. Canvases need priming and stretching, sculptures casting, and brushes cleaning.

Dora Maar is a great example of a muse who provided support beyond simply posing for her portrait, and you can clearly see this in Picasso’s paintings.

An artist herself—she was a successful Surrealist photographer—Maar left an indelible mark on Picasso’s practice. In her darkroom, she taught him to develop black-and-white photographs, while outside it she indoctrinated him in her ultra-Left-wing politics; both infused not only Picasso’s portraits of her, but the epic anti-war mural, Guernica (1937).

Maar was the one who found Picasso a studio large enough for his huge protest painting—the site was the former headquarters of her radical political group, Contre Attaque. Inside the space, Maar photographed Picasso making the mural and helped him with sections of painting it. Leaving his bright palette behind, he created Guernica in black and white, influenced by Maar’s photography. There is even a darkroom spotlight in the picture, beneath which appears, for the first time, Picasso’s famous Weeping Woman.

Maar’s practical support and creative influence were career-changing for Picasso.

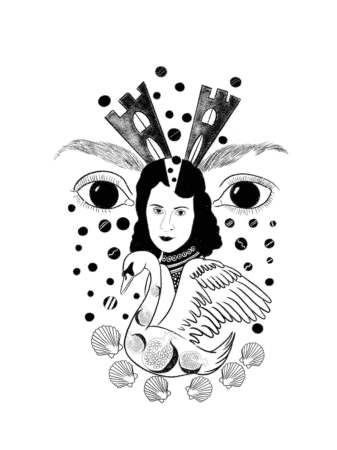

PT: It’s great to see that you’ve worked with illustrator Dina Razin—and that the UK version of your cover is her re-imagining of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. Could you tell us more about that collaboration?

RM: I’m glad you’ve used that word, collaboration, as that is exactly what this project has been from the start. It was an honour and privilege to work closely with Dina on the cover and 32 illustrations for the book.

Dina has such a beautiful style, inspired by her rich Middle Eastern heritage. She also focuses on bringing to life incredible women, past and present, in a contemporary style. So I was over the moon when she agreed to illustrate the book!

For each chapter and muse featured, I briefed Dina on the most important aspects of their story, and provided her with images of the artworks I discussed in the text. Dina would then draft an image, sometimes more, and ask if this represented the muse appropriately.

Dina was incredibly skilled at weaving layers of the muses’ narratives and different aspects of their identity into one symbolic image. For example, her image of Luisa Casati shows the Italian heiress in a gondola with one of her pet leopards, her hair a bed of snakes—many artists portrayed Casati as a wild Medusa figure because of the extravagant parties she threw, the outlandish costumes she wore (including live snakes around her neck), and her overwhelming desire to become “a living work of art.”

In the process, these muses became our world. When Dina sent over the final illustration for inclusion, I cried, as this journey was over. But, I do hope (and plan!) that we will work together again…

PT: What would you imagine a professional artist might especially enjoy about reading Muse?

RM: I think it will strike a chord with portrait artists who work closely with their own muses.

I do hope that women artists will enjoy the chapters focused on the likes of Sylvia Sleigh and Kim Leutwyler, who have turned their female gaze on male, female, and non-binary muses. Many of the narratives also emphasise the notion of mutual muses, which perhaps some artists will identify with. Great art is never created in a vacuum.

Contemporary culture also invites us to consider ourselves our own muses—with selfies on social media—so I hope the section on “Self as Muse” would be of interest to artists and anyone who has ever published their own self-portrait online and thought about issues of consent, control, and ownership.

I think there is a story for everyone in Muse.

PT: How can people buy a copy of the book?

RM: Muse will be sold by various retailers in the US—you can find out who and where here: simonandschuster.com/books/Muse/Ruth-Millington/9781639361557

PT: Thank you so much for sharing your work with us, Ruth!