Art isn’t just a noun, as in an “art object.” Art is also a verb—as in it can do something or change something. Art shifts perspectives, builds resistance movements, facilitates community development, and shifts cultural and political norms and expectations.

Art In Today’s Climate

It’s no secret that we are in troubling times. As populism spreads, it is increasingly rearing its ugly head—flagrant white supremacy, anti-women and LGBTQ policies, climate change denial, and a turn against access to education and culture—art by and for the people is needed more than ever. Populism uses the idea of “the people” to support the interests of a small part of the population while discrediting the needs of the rest; art is one way that diverse perspectives can cut through and be heard. But how we think about art and art institutions has to change too, so that more people can actually see the work and have the chance to be moved and changed by it—all signs suggest that this is beginning to happen.

The over-saturation of messaging and content makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly how art is contributing to social change today. In order to even begin to figure this out, we’d need to start by distinguishing what “art” is in the onslaught of advertisements, political propaganda, memes, videos, GIFs, and clothing slapped with branded slogans. But we’re not here to answer impossible questions about visual culture. Instead, let’s take a look at a few examples of artists and art that are successfully affecting social and political change today.

Art Changes Everything

One of the most well known anti-establishment artists working today is Banksy. Banksy is an anonymous activist artist whose work focuses on social commentary and is generally anti-war and anti-capitalist. The “accessible street art” stencil style has shown up on buildings and sidewalks across the world, and has been emulated by hundreds of other artists. While Banksy no longer sells work in a traditional sense, and generally doesn’t display them in typical art institutions, Banksy has made artworks as a commentary on the commodification and commercialization of art and the absurdity of the current art market. The self-shredding Girl With Balloon featured at Sotheby’s in 2018 is an example of this commentary in action, and an interesting example of how art can be an active, surprising, and ever-changing force.

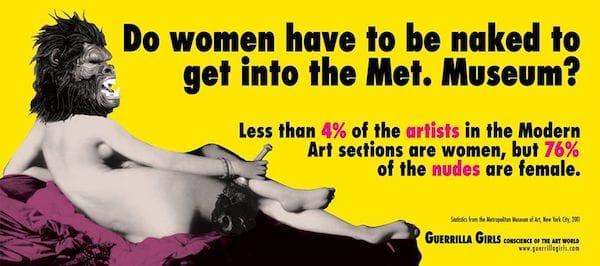

But before Banksy, there was—and still is today—the Guerilla Girls. This anonymous activist art collective has spent the last thirty years vocally fighting racism and sexism in the art world. They do this by plastering facts across public billboards and murals and showing up in full gorilla costumes to protest art-world hypocrisies and injustices. This poster has become a symbol of furthering female representation in art institutions:

In China, the artist Ai Weiwei has highlighted numerous social issues through his installations and sculptures. He has used his work to comment on cultural change in China, and even to document his own persecution and imprisonment. Photographer Nan Goldin has used her art and recognition to protest against the opioid crisis and companies profiting off of addiction to OxyContin, and was arrested within the last few months for rallying in protests calling attention to the Sackler family’s direct involvement. Architects Ron Rael and Virginia San Fratello installed their now famous Teetertotter Wall—which brought together Mexican and American residents from either side of the wall on the Southern border—to challenge the politics of fear, hostility and exclusion that often dominate discussions of the border. Kara Walker’s black silhouetted cut-outs depict the sexualized interactions of white slave owners and black slaves in commentaries on the degradation of the “peculiar institution” that is a foundation of American systems and power. Artist Nina Chanel Abney has taken a rightful seat at the table with her paintings that explore race, gender, pop culture, and homophobia. Bright and full of color and symbols, she calls her work “easy to swallow, hard to digest.”

In China, the artist Ai Weiwei has highlighted numerous social issues through his installations and sculptures. He has used his work to comment on cultural change in China, and even to document his own persecution and imprisonment. Photographer Nan Goldin has used her art and recognition to protest against the opioid crisis and companies profiting off of addiction to OxyContin, and was arrested within the last few months for rallying in protests calling attention to the Sackler family’s direct involvement. Architects Ron Rael and Virginia San Fratello installed their now famous Teetertotter Wall—which brought together Mexican and American residents from either side of the wall on the Southern border—to challenge the politics of fear, hostility and exclusion that often dominate discussions of the border. Kara Walker’s black silhouetted cut-outs depict the sexualized interactions of white slave owners and black slaves in commentaries on the degradation of the “peculiar institution” that is a foundation of American systems and power. Artist Nina Chanel Abney has taken a rightful seat at the table with her paintings that explore race, gender, pop culture, and homophobia. Bright and full of color and symbols, she calls her work “easy to swallow, hard to digest.”

CHF Art-Business Accelerator Fellow Robin Holder’s “global village” bridges the gap in the polarization of race, class, religion, and politics by connecting a diverse society. With her self-described “social justice imagery” inspired by her own experiences, she encourages community dialogue about identity conflicts, and fosters awareness and appreciation for our diverse society. Mauelita Brown, another CHF Fellow, creates figurative sculptures that transform our view of “the other” from suspicion and fear, to connection and empathy. Both of these artists use their work to connect communities and break down stereotypes and misconceptions about identity and cultures.

After Michael Brown was shot and killed by police in St. Louis in 2014, artist Dread Scott released an image of a piece called Sign of the Times which he had originally made after a 23 year old immigrant named Amadou Diallo was shot by police 41 times in NYC in 1999. The screenprint is reminiscent of yellow and black traffic signs with the text “Danger: Police in Area” and is a still timely commentary on racial profiling and excessive police force used against black and brown boys and men. This November, Scott and 500 Louisians reenacted America’s largest plantation slave uprising over the course of a two-day performance art piece called Slave Rebellion Reenactment. He describes his work as “revolutionary art to propel history forward.”

Withdrawal Works

The removal of an art object from an exhibit, or an artist opting out of participating in an event or show because of an institution’s connection to a social injustice, can also help further social progress. One recent example of this is from this year’s Whitney Biennial. Eight of the highly prestigious biennial artists withdrew from this show citing the museum’s inaction to remove museum board member Warren B. Kanders because of ties to the sale of military supplies—including tear gas that has been found to be used in law enforcement and at the detention camps at the US Mexican border—as the reason. This included design group Forensic Architecture who, in collaboration with Laura Poitras and Praxis Films, has one of the most talked-about pieces in the biennial titled Triple-Chaser. The piece focuses on Kanders’s philanthropy and connects him and his companies Safariland—which manufacturers tear gas—and Sierra Bullets— which manufacturers bullets used by the Israeli Defense Forces—to many international wars and criminal atrocities. Pressure from the artists resulted in Kanders resigning as vice-chair in August. And while the artists were ultimately successful in ousting Kanders, they are now working to hold the museum accountable by demanding that they resist “toxic philanthropy.”

Similarly, when Hudson Yards board member, Stephen Ross, recently held a fundraiser for Donald Trump, many artists who were scheduled to perform at The Shed (a performance art space on the property) withdrew in protest and to help bring attention to Ross’s support of Trump and ultimately of the derailment of equal rights, as well as to the hypocrisy of the art world leveraging big money against the lives of its artists. It is in these moments that the art world remembers who their viability is dependent on: the artists themselves.

History Speaks

But art doesn’t just comment on moments in history or influence public discourse…

Art Heals

Holy relics in churches are meant to comfort, cure, and restore. Dadaism was founded to advocate for silliness and nonsensical behavior in daily lives for those faced with the horror of WWI. Navajo ceremonial sand paintings are used to compel Gods to guide in times of struggle. The creation of the WPA Federal Art Project during the Great Depression brought both economic stability and a sense of purpose to artists and craft workers working nationwide. And in the 1980s, Keith Haring not only used art to expose the AIDS crisis, which generated activism and awareness, but by talking about his own illness, he helped destigmatize AIDS and bring others together to build a supportive community.

These examples—among many others—represent how art is critical to both upending oppressive social orders and then re-affirming community and getting us through trauma.

Building Bridges

In a time plagued by campaigns like “fake news” where both factual information and a free press are threatened, artists play a crucial role in salvaging truth and transparency—critical elements of a democracy. By exposing corruption, corporate greed, effects of climate change, deep-rooted systemic racism, gender and LGBTQ inequalities, and successfully galvanizing people to rise against oppression and insist on something better, art is doing what it should: it is speaking truth to power. It is taking down walls and building bridges. It is bringing people together to enshrine on our collective ethos, a fundamental commitment to equal rights and access for all. It is shining a light on not only what’s wrong in the world, but what’s right. Art is creating a culture positioned to propel history and progress forward.

Action & Advocacy

Art moves. It shakes. It heals. It connects. It illuminates. Art breaks down barriers and builds communities. When we let it, art extends beyond a tangible object and becomes a verb that shifts history. It is up to us to champion artists and art, and unleash their inherent power to better ourselves and our world.

Fantastic article Alex. The Arts can help us get through this difficult time. Your words are inspiring and provide a rich overview of the possibilities when art and social justice combine.