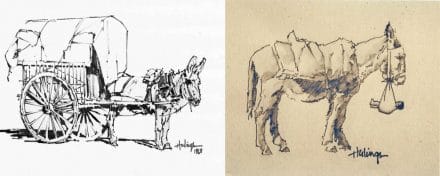

As fans of Clark Hulings’ artwork know, donkeys are a recurring subject in my father’s paintings. He loved everything about them. He named the publication arm of his art business White Burro Publishing (burro is the Spanish word for donkey). His logo was a donkey and cart, and it appeared on my birth announcement. My son’s birth announcement included a drawing he did of a donkey holding a baby in a sling in its mouth–no storks for the Hulings!

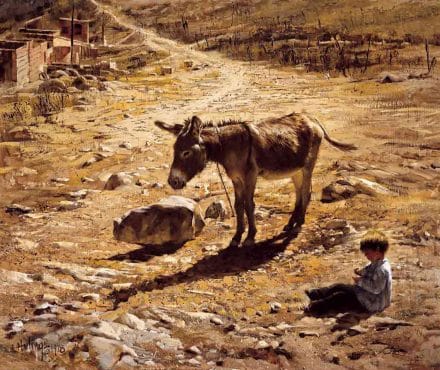

As a self-described “backdoor painter,” his affinity for donkeys makes perfect sense. They are the working man’s beast of burden. Horses are elegant and sleek; donkeys are scruffy and stubborn. My father identified with the latter. He understood that their determination, loyalty, courage, intelligence, pragmatism, and resilience are the same qualities that enabled him to succeed as an independent artist.

Donkeys do a lot of lowbrow work. They slog through mud, carry enormously heavy loads, stand in the sun, rain, and snow, and wait. Ranchers leave them loose among the herd at night because they will attack coyotes and stomp on snakes. Donkeys don’t stand on ceremony or second-guess their decisions. If they can’t see where they are going, they WILL NOT back up! You can walk a horse off a cliff. Not a donkey.

Not Just Tough—Burro Tough

My father built his career by being similarly fierce and determined. He slogged through the mud after the farmer, stood in the sun at the market, and let snow fall on him until he got double pneumonia–all to get the material he needed to create his art. He worked a minimum of 42 hours per week in his studio (six seven-hour days or seven six-hour days), even if that meant painting at 3:00 AM because he had spent the afternoon crating and shipping a finished piece.

While he would have been happy to spend all of his time painting, he understood that other aspects of his business demanded attention, too. That’s why he painstakingly built a sales pipeline for his work that included multiple channels. He took a smaller percentage from galleries that agreed to split advertising costs with him–because otherwise they might not advertise at all. He went to all the openings, wrote personal notes, and took art directors to lunch, even when the meal cost more than the last job they’d given him.

Clark Hulings was an entrepreneur whose business was easel painting. He never let anything out of his studio that he deemed “unacceptable,” and I watched him put a razor blade through pieces that I thought were more than acceptable. He painted what interested him, what helped him express himself, and he steadfastly refused commissions or invitations to shows that demanded he depart from that. However, he also understood the market and was willing to put his creativity into service, finding angles to sell “acceptable” pieces that might not have been his favorites, and to find ways to meet outside requirements without compromising his vision. Intransigence? Maybe. Pragmatism? Definitely. Successful business owners exercise both.

Like Burro, Like Artist

Art is a tough business. My father’s advice to people who were considering a fine-art career was, “If you can imagine yourself being happy doing something else, then just do that now, and make art on the weekends. If not, then you are truly lucky because you have no acceptable alternative, and therefore, will succeed in the end. It might take a long time, but you’ll feed yourself if you keep at it.”

If you work without a net, you can’t fail–unless you don’t do ALL the work. That includes paying sufficient attention to the distribution of your creations. You can’t stand on ceremony. The greatest thing you ever make will be for your eyes only if you don’t work like a donkey to get it to market. Clark Hulings was a very successful artist–but not until he was 55 years old. Up until that point, he was a striving artist and a determined businessman. And the qualities he admired in donkeys were ones that helped him feed himself (and me!).

[Burros] are very strong…but they do not misuse their strength…. If left to their own devices and their own pace, they will serve well …. They can be trusted.” —Clark Hulings, A Gallery of Paintings

I so love this new series… It’s so interesting to learn the back story.

This is a wonderful and inspirational article. Thank you for sharing your father’s story!

Such a good lesson and fascinating story. Thank you Elizabeth.