It’s axiomatic that when an investor puts money into a business, they want to get that money back out along with some factor of growth. Warren Buffett defines investment as “laying out money now to receive more in the future.” Stocks, bonds, funds, ETFs, and REITs are the typical investment vehicles, though direct investment through venture capital perhaps better underscores the point–when you put money into a business (or any enterprise), you expect to recover it with profit. Investment is not a gift–except when it is.

There’s a False Divide Between Investment and Philanthropy

The contrast between investment and philanthropy is often characterized as getting a return or not getting one. You give to a non-profit and, in a rather obvious turn, you don’t profit. Ayn Rand, the 20th century’s philosophical champion of fair trade capitalism, would call the inequality of such an exchange a monstrous form of sacrifice or enslavement of one party for the benefit of the other.

A whole generation of heirs to the Austrian School of Economics simply does not respond to the notion that you must give without any hope of return, because otherwise you’re not a good person.

That’s seen, rightly I would suggest, as a kind of moral shakedown. For those who have read Atlas Shrugged, the character of Hank Rearden (Rearden Metal) calls this out as a backhanded slam against those who have invested their lives and made their livelihoods by prioritizing a return on investment (ROI), whether of their energy and labors or their capital.

But twin new movements are afoot in investment and philanthropy.

Social Investment Gets Us Only Part of the Way

On the investment side, a philanthropic (or ‘social impact’) focus is not really that new anymore. Social investment or socially responsible investing (SRI) began to pick up steam in the 1990s, and is perhaps best exemplified now in the new generation of captains of industry like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos, and the emergence into the marketplace of the silicon valley philanthropist (as a thing).

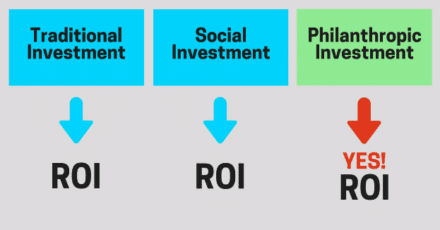

Social investment, for anyone new to it, is investment strategy aimed at financial return with resultant social good. Investment in renewable forms of energy is a frequent example. The objective of social investment is to select opportunities to profit that have significant social impact. If non-profits are wondering where their money is going, it’s not just to stingier use of public funds or tighter purse strings all around (though economic uncertainty plays a role). Social investment provides those with philanthropic interest the thing a capitalist needs most–a return on investment (ROI).

Fortunately, itemized tax deductions for charitable giving still interest us (though who knows with the new tax bill?), and the general demeanor of many capitalists toward society is positive. They’re not just buying apocalypse land in New Zealand–that’s an investment hedge–they’re also trying to hold the culture together.

But this distinction between a benefit for the philanthropist and no benefit at all is emerging as what separates philanthropy from charity. By way of illustrating the attitude, we say artists are not looking for a hand-out, but for a hand up to self-reliance and entrepreneurship. So how does that help the philanthropist? A corresponding movement (to social investment) is required in philanthropy–namely charitable opportunities that produce an overall economic result.

Philanthropic Investors Demand Philanthropic ROI

Obviously, philanthropy does not amount to writing a check to a non-profit, and later getting The Foundations back with interest. That’s a loan. But giving and getting nothing turns off a lot of business-minded philanthropists, especially with so many social investment opportunities.

The opportunity for philanthropic ROI lies in producing demonstrable impact on the economic environment–not just of a non-profit’s constituents, but of its donor-investors. That’s the pivot wherein a donor actually becomes an investor, without abandoning the self-interest that defines investment as an exchange.

Philanthropic ROI applies the principles of social investment to philanthropy–with three principles:

- a tangible economic benefit to the investor

- a visceral benefit to an identified group of constituents

- a positive social outcome for society as a whole

This is alien language to many non-profits, even as they feel the pinch of funds going to social investment and simultaneously cuts to government grants and subsidies.

Philanthropic Investors and Visual Artists are Natural Bedfellows

The idea that philanthropy benefits the philanthropist is widely regarded as heresy in the philanthropic world. It’s the fear of moral dirt, or the corresponding commitment to a (false) purity. Saying a philanthropist should factor his/her own benefit in giving is like saying an artist should strive to make a profit.

Yet, the parlance and demeanor of investment requires it. Investing isn’t throwing money away, or throwing it at the wall and hoping what sticks is some social good. It’s producing a tangible result that impacts the investor as well as the recipient of investment.

How We Produce Philanthropic Return for Investors

We think we’re on solid ground, therefore, by saying philanthropic investors and visual artists are natural bedfellows.

We argue that giving to a Fund that transforms visual artists into artist-entrepreneurs:

- Strengthens the general economy, by ensuring an entire sector of wealth and capital creators thrive, while simultaneously reducing the burden of sustaining a previously under-performing work sector.

- That stronger economy, with more wealth/capital-creators and job-creators (starting with full self-employment for visual artists) is the very platform on which investors rely. In effect, the ROI is in a more stable, robust, opportune investment platform (the economy itself) and (were the investor inclined) in a particular market sector that has related investment opportunities.

- The social good produced isn’t just one-to-one, making a particular vocation self-sustaining but, as the economic prosperity of artists ensures a place for art in a profit driven era, it’s an investment in the aesthetic and cultural environment of humanity as well. An economy of self-reliant artists produces a society of aesthetic delight.

The Economic Benefit of Aesthetic Renaissance

That last part isn’t fluff; the Medici in Italy created a renaissance that filled the world with art by enabling already working artists to become independent ‘merchants’ who ran businesses filling orders in a commerce of art we would later recognize in one word ejaculations as being a Michelangelo, da Vinci, Donatello, or Botticelli.

Investment in an art-business economy, that allowed working visual artists to become self-reliant, was the lever that tipped the globe. It triggered an economic revival that spread outward from Italy, putting solid ground under the feet of commercial interests and starting an engine of incredible innovation that swept the known world.

The other result was that everywhere the eye landed in the world that grew out of that Florentine economy, there was art. That enabled not only Florence, but the entire Mediterranean world, to live in an exciting (and more deeply shared) culture that stimulated thoughtful and creative dialogue and fueled the dynamo of ideas. We have a legacy not just of portraits of minor patricians, but of masterpieces from that time, precisely because of the philanthropic investor. Philanthropic investment is not so much a new invention as a rediscovery of what gave us so many new inventions.

Ensure Philanthropic Options are Investment-Grade

Sustainable philanthropic investment is going to require even more demonstrable economic impact than just arguing the case in principle. I would propose these tests to gauge investment-grade opportunities with philanthropic organizations:

- How the Engine Works: Demonstrate in principle that investment will enable the target group of constituents to become economically self-reliant. The investor sees self-reliant individuals as the ‘motor’ that drives the world. If we can’t explain how the motor operates, we don’t deserve the investment.

- Performance Metrics: Provide performance metrics on the operation of that motor. What demonstrable change is investment producing that ensures the motor is self-sustaining, and won’t run out of gas the moment The Foundations are spent, requiring an endless refuel for each constituent?

- Overall Economic Relationships: Demonstrate in principle the overall economic relationship of individual activities by the constituents to society. It’s not enough to say they do good or produce good; what good do they do that has an economic/financial impact on the world?

- Overall Economic Impact: Document specific, measurable outcomes for society. If one working artist moves from 30% economic sustainability to 100%, what burden is lessened, and what contribution is increased, and what is the ultimate impact even with many zeros in front of the decimal point for just one artist?

- Efficient Assembly Line: nothing gets investors upset like bloated production costs or, in the ‘nicer’ terms of traditional non-profits, unnecessary overhead. Perhaps the most profound way a philanthropic investment opportunity can show ROI is in percentage of invested capital going toward programming vs. admin. A competitive investment is going to know what that number is and strive to keep pushing it downward

Final Thoughts

If I’ve made anyone uncomfortable with these observations and suggestions–good! Some discomfort is a precursor to change, or acknowledging that change. I contend that a shakeup is happening that demands tighter accountability, sure, but also a shift in focus for philanthropic providers, because ‘charitable givers’ are becoming philanthropic investors.

The venerable ‘old money’ is a shrinking pie, as blue blood wealth gives way to silicon valley wealth. But also, there’s nothing wrong with a demand for clearer impact and a clearer relationship between the world of social good and the concerns of capital that funds it.

This is going to become more a ‘thing’, because it can. It’s the natural evolution of the market. Non-profits can’t claim market-immunity any more than professional artists can. There is no institution, not even perhaps the Church, that can ignore The Foundationamental expectation that value be provided for value. It’s ethically just, it’s here, and it’s going to require us to stretch to respond, and I would aver that that’s healthy and good for all of us.