“If you would be reasonably satisfied doing something else for a living, then do that and paint on the weekends.” —Clark Hulings

Primary-Care Perspective

When my father was in his eighties and preparing for what would be his final solo show, he went in for an annual check-up with his physician. During the visit, the doctor asked him about his own son, who wanted to be a photographer. He told my father that his son wanted to go to art school, but that he (the doctor) was concerned that the young man would never make a living as an artist, so he was trying to persuade him to go to college and study computer science instead, with a minor in art. Apparently, the son was quite good at computer science and “kind of liked it.”

“Does he ‘kind of like’ photography, too?” asked my father.

“Oh, no, he loves photography; it’s his passion,” replied the doctor.

“THEN THE WORST THING YOU CAN DO IS PUSH HIM TO DO SOMETHING ELSE!” responded my father, so vehemently that the physician had to toss out the results of the just-concluded blood-pressure test and re-apply the sleeve to my father’s arm. “If your son can imagine being satisfied with his life as a computer scientist, then you are right to persuade him to study that subject,” he said, explaining his outburst. “If, however, he would simply be doing it to placate a father who’s worried about his son’s financial security (which is completely understandable—I’m a father, too), then he must throw himself into his photography and make a career of it.”

Woodworker, Farmer, CEO

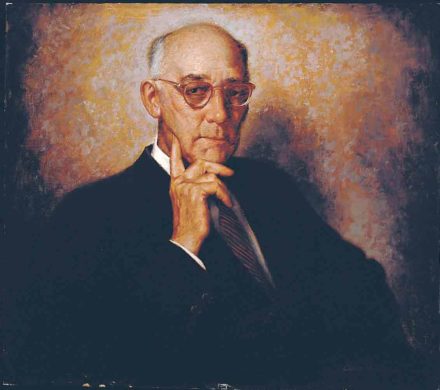

At the age of six, my father drew a pastel portrait of his stepmother that deftly captured her likeness, and he brought it home from school. When his father saw it, he said, “Looks like we’re in trouble. We have a budding artist on our hands.” My grandfather, Courtland Hulings, loved art and collected it—he was himself a woodworker, and my mother and I still have many lovely pieces of furniture made entirely by his hands, using wood that he’d chopped down himself—but it never occurred to him that one could earn a living from art.

Courtland was very driven, a true force to be reckoned with. After fighting in France during World War I and rising to the rank of colonel, he returned to the US determined to achieve his goal of becoming a farmer. After the war, he and a friend bought land in Brewster, Florida, with the idea of growing oranges. A trained chemical engineer, Courtland had planned to apply that expertise to raising resilient crops.

His dream fell apart, however, when his wife, my father’s mother, contracted tuberculosis. She passed away when my father was a baby, and my grandfather took the most lucrative job he could find so that he could afford to raise his children as a single parent. He left my father and his older sister in the care of their mother’s family and went to Valencia, Spain, to apply his cutting-edge fumigation techniques to their orange groves instead of his own. For the next 30 years, he stayed firmly on a business track and went on to serve as the CEO of Copolymer Corporation, a joint partnership of seven US rubber and tire companies that joined forces in 1943 to develop a process for manufacturing synthetic rubber (because our country’s supply of natural rubber was being threatened by the Japanese during World War II). Eventually, old age arrived, and Courtland retired to a small ranch to enjoy horseback riding and gardening, but he never did realize his dream of becoming an orange farmer.

Don’t Try to Ignore the Muse

In the middle of the Great Depression, Courtland’s 12-year old son began using a cheap paint set he’d gotten for Christmas—making copies of The Calmady Children by Sir Thomas Lawrence, and the works of the Ashcan School artists that were on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art—and waxing on and on about Sargent and Eakins and, and, and…. until Courtland finally gave in and sent the boy for lessons with a Russian portrait painter who happened to live down the block. By the time Clark graduated from high school, the TB that he’d inherited from his mother at birth had reared its ugly head, requiring extended rest and delaying college. As a result, Courtland let him go into New York City to study drawing at the Art Students League, as long as Clark agreed to spend every morning in bed.

By the following year, Clark was stronger and finally ready to head off to college. He begged to be allowed to forego university in favor of full-time art school, but his father rejected that idea out of hand. To Courtland’s mind, art school would never prepare his son to support himself economically, and it was imperative that Clark contribute to the war effort. Since the TB meant that he was 4F, my father was forced to attend Haverford College instead, where he majored in physics and hated every minute of it.

Needless to say, college did not vanquish the muse. After the war, my father began painting portraits, which immediately brought him acclaim. Governors, debutantes, and businessmen alike demanded to sit for him. In 1948, Courtland once again gave in to his son, and supported Clark while he returned to the Art Students League to study full time, which finally allowed my father to get the training he wanted and needed.

In 1952, he launched a career in illustration, working like a dog and saving every penny. Six years later, he took a line of credit, pulled up stakes, and went to Europe to “turn himself into an easel painter.” In 1966, Grand Central Galleries gave him his first solo show, and he never looked back. Eventually he repaid every cent that his father had invested in his art training at the league. The Artist bested the Colonel, with the muse getting her way in the end.

The Danger Of Safety Nets

“Had I been allowed to go directly to art school, I would be a great artist.” —Clark Hulings

“You have to let your son follow his passion,” my father told his doctor that day. “If he has something else to fall back on, it will make it harder for him to keep striving as a photographer. Safety nets strangle you. Also, the younger you start, the better. Now is the time for him to learn, acquire skills, and shape his talent. Had I gone to art school directly after high school, I know that I would have developed much greater technical proficiency. Your son can always study computer science later if he washes out—which he won’t if he really goes for it in a pragmatic way now.”

My father knew this from experience. The professional artist is driven to create art and show it to the world. Everything else takes a back seat. So the only rational way to approach life as a professional artist is to:

- Never Stop Learning. Get all the training you possibly can, as early as possible, and then supplement it continually. Waiting until your finances are stable or the kids are off to college is a ruse because you will have spent much of your life NOT following your vocation—not doing the job you were put on the planet to do—AND you won’t be able to learn as well as you would have when you were young. Hand-eye coordination must be honed in youth. We don’t tell budding tennis players or gymnasts to get a law degree first, practice for a couple of decades, and THEN start doing back flips or serving up 120 mph aces.

- Commit to Being an Artist. View “artist” as your professional title; anything else you do to earn money while your artist income lags is a sidebar. Figure out what you can do to support yourself so that you can continue to focus like a laser on your art. If you devise an income-earning activity that relates directly to it, great, but don’t fall into the trap of working in an art-related business and then fooling yourself that you are still a professional artist. Professional artists make art and display that art to the world. Professional lawyers are paid to practice law. (While politicians use their law degrees as credentials for a different occupation, most people would rather hire a professional lawyer—not a career politician—to defend them in court.)

A Tough-Love Prescription

While I was visiting my mother a few months ago, I accompanied her to the doctor—the same primary-care physician who’d been on the receiving end of my father’s impassioned plea on behalf of his son all those years ago. As his patients checked their watches and bothered the receptionist, the doctor related the story of that earlier visit.

He said that it was one of the seminal moments in his own life. He told his son that he would not allow him to do anything else until he had truly pursued photography AS A CAREER, because he knew that the young man would succeed. And the son did succeed—because of his father’s faith in him, but also because his father had held his feet to the fire. He had compelled him to be professional about his passion. Thanks to that father, the rest of us get to appreciate the son’s work, and the world is richer for it.

If you’re NOT sure about pursuing art as a career, or if there is something else you can imagine yourself doing that will keep you reasonably fulfilled, then don’t try to be a professional artist. However, if you know in your heart that it is what you’re meant to do, then do it. No hiding. Be clear-eyed and honest with yourself. Look at the reality of it and tell it like it is. Not an easy thing to do, but then who said the job of an artist was easy?