Janet Culbertson is an award-winning eco artist who has been making art for over five decades. In this conversation with Jennifer Orbom, Janet discusses marketing ‘difficult’ art, her business’ evolution, and what a successful artist looks like.

JO: Tell me about your first big sale.

JC: It was big for me because a gallery typically handled all sales, but I handled this one. Someone came to my open studio and the sale was for $4,000—pretty decent 15 or 20 years ago—and it was one of my favorite pictures. I was doing silverpoint drawings in those days, and the gallery didn’t charge much for works on paper.

That silverpoint show practically sold out. The few that didn’t sell are now in the Telfair Museum.

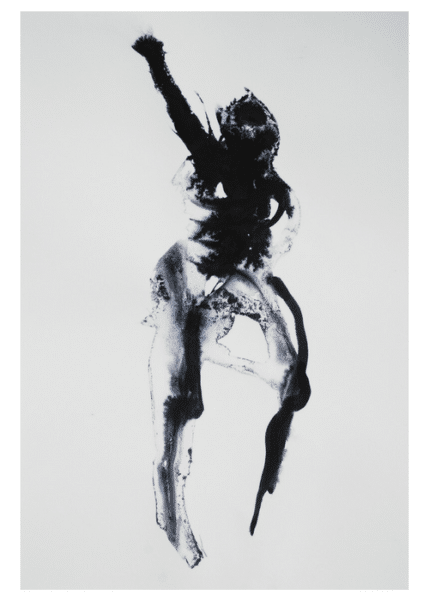

JO: Your silverpoints, inkworks, and paintings are all different styles, it’s one of the first things I noticed.

JC: They’re different because I love to experiment with new techniques. That keeps me fresh. I never went in for the philosophy that you get one look, and do it forever. I like to experiment, and create new media, and that’s part of the fun of it. Although, I always do imagery about nature and the environment.

Once in a while I pound you over the head with a message, but I try to portray the artistry and still have a message. It’s an interesting balance that artists have, but I do think, for me, art has to say something. I don’t connect with decorative art. You might as well hang a nice piece of fabric if the art doesn’t say something.

JO: Do you describe your art as political?

JC: Any art with a message is political. And most people consider trying to save nature political—I consider it essential. I consider what I do to touch on realism. I’m not fabricating anything, this is not fantasy, I depict things that are happening. Some people say, “Well, why don’t you just focus on the positive?” But that doesn’t seem to have enough of an impact for me. I have done a whole series of works that were so-called “beautiful” landscapes, and I enjoyed doing those when I was first starting out back in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Then I traveled and I saw changes taking place.

JO: Can you tell us about marketing your work? Does the political, or radical, element enter into marketing?

JC: Well, it doesn’t make for decoration. The first works that sold out were the silverpoint pieces, followed by the early landscapes depicting islands and beautiful places. Then when you put a message in there, it suddenly goes off in a slightly different direction. So, what I’ve found is that I get appreciation in universities, alternative spaces, some museum shows. A very commercial gallery won’t often take a risk and show political or difficult work. They may if the person’s very well known, like Anselm Kiefer, the German artist. Look him up, he’s incredible, his work deals with all kinds of really difficult issues. But of course, he’s making millions from it.

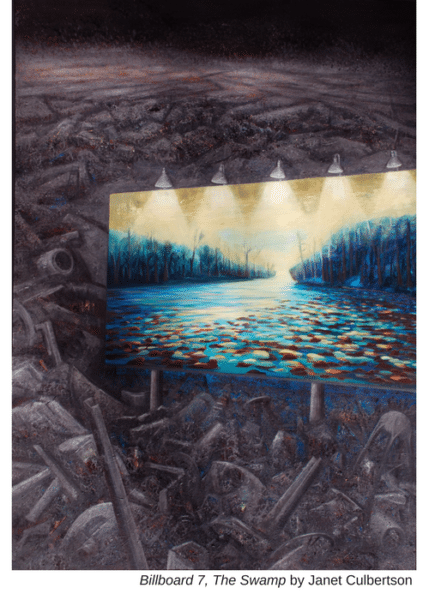

My billboard series was a very important direction for me. I was driving through Elizabeth, New Jersey in the late ’80s and it just looked like a ravaged site, with polluted-looking areas. Off in the distance I could see the Statue of Liberty, and billboards in the foreground. The whole thing coming together was so jarring, and un-beautiful. So, that was the first billboard painting I did: a ravaged site, with a lovely wilderness scene on the billboard as a reminder, “This is what you’ve destroyed.”

My work fits within political-social issues, the environmental and nature. I have large drawings of animals, some endangered, and I’ve sold prints of those. These are large: eight or nine feet. I’ve been able to sell some very nice, but smaller, archival prints. They’re better for somebody’s living room, and then I still have the original for exhibits or for whatever shows might come up.

JO: Do you consider art to be your career?

JC: It’s the focus of my life. I don’t have children. I didn’t feel I could handle all that, and fortunately it worked out okay.

JO: You never had to do art on the side while working a day job?

JC: I did, actually! When I first came to New York from college, I came with, like, $50. It seems unbelievable. We slept on a friend’s couch until I found a job with Display Company on Fifth Avenue and got a rent-controlled apartment. I scraped along for a few years and decided I better take courses so I could teach art at a decent college. I took my masters at NYU, attending evenings and weekends until I finished.

I got a job at Pace College, so I had more time to paint. Teaching was demanding, but it was also inspiring. When you’re teaching, you’re working with art all the time, and with people that are interested in hearing about it.

JO: How did your business develop?

JC: I managed it myself. The Women’s Movement was helpful. We had a group in the city called Women in the Arts, which helped women see that you had to be your own PR person, you couldn’t be modest and defer and always stand back. You had to say, “Please look at my work,” take it around, find shows, put your name on things. That group had some pretty smart women. Alice Neel was one I admired; she would show with anybody because she wanted to get her work out there. She eventually got a show in the Whitney. She brought my husband and I home to her studio to give us her book about the retrospective and offered to paint us for only $3000. I wish we could have done it! She was an incredible person.

With business, you start to learn. I carry cards or postcards. When I meet new people that are interested in art, we talk about seeing each other’s websites. You have to do a lot for yourself if you don’t have the means, and by this I mean the money to hire a PR person or to pay for your own gallery shows, which some people do. It’s one way to get your work out there, but people usually prefer not to do that because it seems less, shall we say, appropriate. I do what I can. Right now, I’m trying to find help with my computer because exhibitions require computer skills. Everybody my age has got thousands of slides, and they’re passé. Nobody will look at a slide anymore!

JO: Actually, Elizabeth [Hulings] has discussed handling her father’s estate, and going through drawers and drawers full of slides.

JC: Do you know what’s amusing? I went to a wonderful museum in Mexico City, where one artist had taken all of his or her slides, thrown them in a heap on a big platform, sprayed them with something, and that was their artwork. I thought, “Well, that’s one way to handle it.”

A lot of people have used debris. I’ve used some in my work. I’ve used little skeletons of animals I found on the beach and put them in my panel work, as a reminder of what happens to creatures. If I find something that has an interesting history, I will incorporate it.

JO: Is your legacy something you think about, or take steps to preserve?

JC: It would be nice if I had a reliable person who loved my work to take it over when I’m gone. It’s a situation a lot of artists have to think about. I have work in over a dozen museums, which doesn’t mean I’m safe forever, but it does mean that some of my work has found its way into a reasonably safe place.

Artists need assistance with this stuff. I have a storage shed filled with work and I need help every so often. I hired people to help me pack and ship a show. It takes a lot of energy—that’s part of the art. You don’t go into the studio every day and paint a wonderful picture. You have to make some phone calls, take photographs, get frames. There’s a lot of housekeeping with art.

JO: How would you define a successful artist? Do you think of yourself as a success?

JC: I think of myself as endlessly emerging. By that I mean: I don’t know what fame is. In the world today, fame seems to be a lot of money. And there are artists that make a lot of money, big-name artists. Of course, once they achieve a certain level, then that has to be maintained and the gallery has to maintain it. The gallery has to keep their name and their prices up, as would their collectors. So, in that sense, I am not a successful artist. I feel good about the work that I’ve done and the message that I’ve worked with, and the fact that some of my environmental pieces have affected and enlightened people. I feel very good about that.

Wonderful interview! Kudos to Janet Culbertson and Jennifer Orbom.