When Shakespeare’s Juliet asks “What’s in a name?”, she’s talking about the battle between two warring families, but the question could easily be directed at the visual art community.

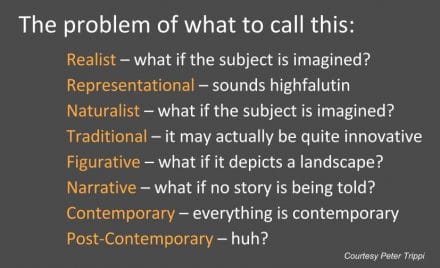

What does it mean to label an artist’s work “modern”? How about “traditional” versus “contemporary”? How should we classify artists whose work evolves from one category to another, or those who dabble in a mix of styles throughout the course of their careers? How do you define the term “fine art”? What’s in THESE names?

Why Do Categories Matter?

Whether it’s art, music, plants, or animals, the human brain is wired to divide things into categories. It’s how we make sense of the world. There’s nothing inherently wrong with doing so. Labels help us to understand and sort information, which also allows us to retrieve it when we need it later. However, when these labels are used haphazardly and pejoratively, they can cause confusion and do a lot of damage.

Look at what happened to my father, Clark Hulings. He mostly painted Europe, yet he was considered a “Western” artist. Although he benefitted from a steadfast following of Western-art collectors who were happy to acquire his scenes of Italian markets and Romanian workers, he struggled to be known in other art markets because of the “Western” label.

Regardless of the art they like, people often lump together work that is in opposition to their preference. So a lover of abstraction might brand as “traditional” anything that fails to fit his/her favored framework, even if there is wide variation among the pieces that are being categorized under that one vague word. “Western” is a label that’s often applied negatively—and assumed to mean “realist”—by those who prefer a more “abstract” aesthetic, when in fact there are many “contemporary” “Western” artists whose work is completely “abstract.”

The same is true of representational art’s most ardent fans, many of whom turn up their noses at works they deem too “modern,” a moniker they use for everything from a video installation to a Giacometti sculpture.

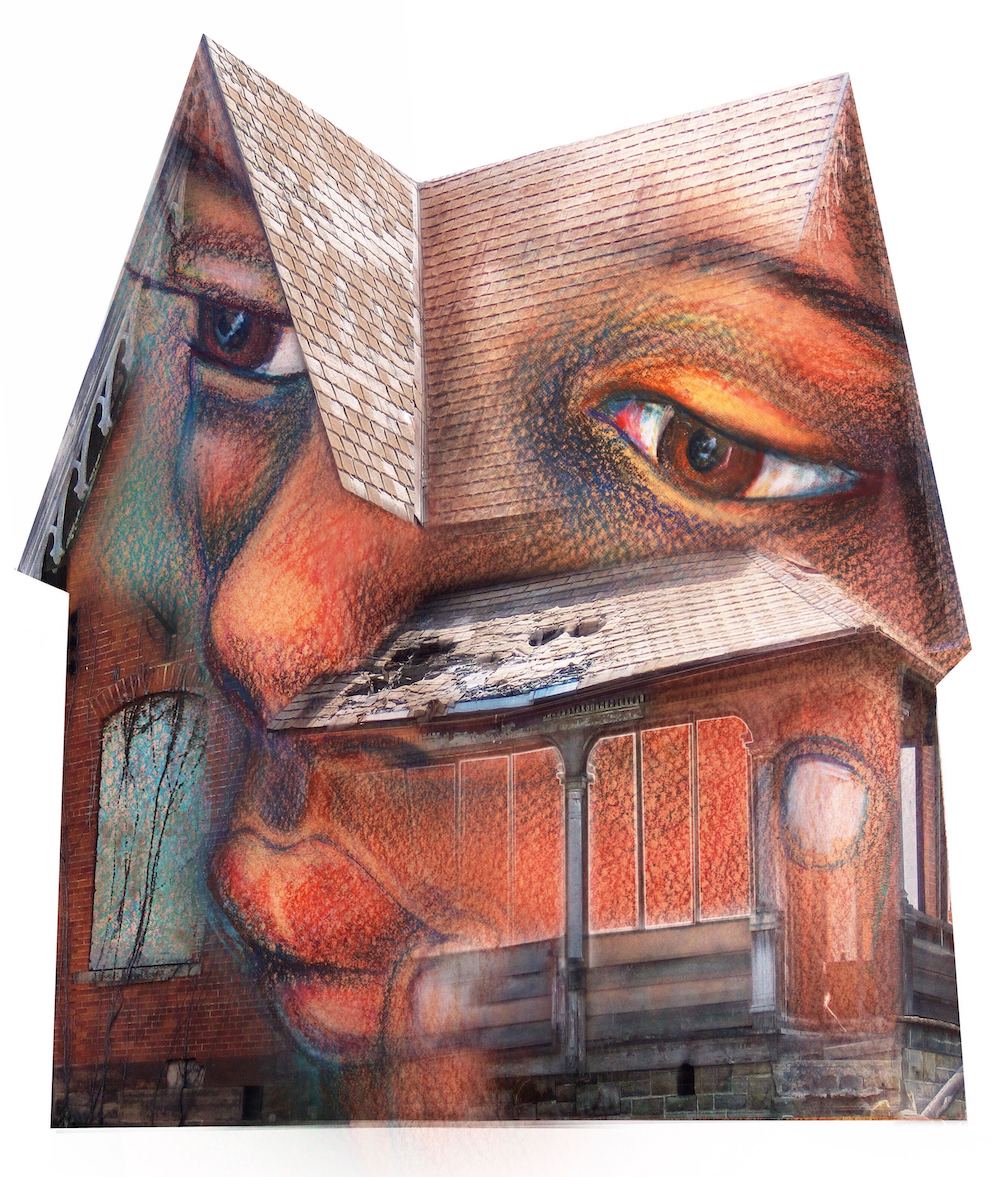

When these labels are applied so indiscriminately, they lose their meaning, but the real problem is that over-categorization facilitates the out-of-hand rejection of those pieces and movements one prefers not to consider. It takes far less imagination to keep the field neat and narrow, rather than confront a new aesthetic or idea. In this respect, the art industry is just like any other: when hotcakes sell, people want to sell more round disks of similar size, color, flavor, and texture.

Sometimes a Rose is Just a Rose

A robust artistic community thrives on lively dialogue, which can produce results as illuminating as they are unexpected. When artists have the chance to grow and follow their own idiosyncratic trajectories, the beauty they create often defies categorization. One terrific example of this is the boundary-crossing portraits that Andy Warhol and Jamie Wyeth did of each other in the early 1970’s.

And even as I write this, New York City’s Museum of Modern Art is featuring the monotypes of Edgar Degas, the first time MoMA has focused a solo show around the work of this Impressionist (yet another label—and one that Degas himself rejected). While Degas’ work may not fit some folks’ preconceived notions of “modernism,” the pieces on display are certainly capable of enriching and rewarding the open-minded viewer.

At CHF, we are stylistically agnostic. How could our organization function effectively otherwise? Where would we draw the arbitrary lines? Categories and labels are useful up to a point, but we shouldn’t be using them to keep artists in creative ghettos. If we truly believe in a free art market, then by definition that market must allow its entrepreneurs the freedom to take risks and create the kind of pieces they want, and offer its buyers the freedom to support the work that moves them, labels be damned.

To receive Elizabeth Hulings’ “Director’s View” column by email each month, please sign up here.

I always wondered about the “Western” artist thing myself. No doubt your dad had some major success in that genre (?), but I remember mostly pictures from Spain. Another interesting thing is that the world won’t see the work of Clark Hulings the photographer in the same way as Clark Hulings the painter. Yet your dad’s artistic vision produced stunning photos as well