I’ve been a business strategist for more than 25 years, and in that role, I’ve helped many different individuals, companies, and organizations rethink their goals and approaches. Some take easily to the process, jumping in head first to evaluate their situations and transform the way they think about and manage their enterprises, but others need longer to understand what I show them.

You see, my job isn’t to hold my clients’ hands and make them feel comfortable. I’m there to help them understand where they really are with their ventures. Often, it is not where they believe themselves to be. If you don’t know where you are, how can you navigate? My job is to point out the elephant in the room, to challenge not only my clients but also the paradigms of the industries in which they work. Instead of guiding them along the same road that many others travel, I ask them to take a step back and really look at the big picture, and then decide where they want to fit into it. Based on that, they might do best to consider a new path, and maybe even a new destination. As you can imagine, this approach is initially much more challenging. It is also infinitely more effective. Differentiation is the key to business success, and it is not found by doing what everyone else always does.

This is as true for artists as it is for startups, nonprofits, boards of directors, and small businesses. In fact, it is more true for artists, because the toll road they’ve been driven onto was built not by their predecessors but by Duveen and co., and it is maintained by dealers and industry experts who are most interested in seeing that the art they support supports them. Furthermore, conditions are changing rapidly, and the road to the soup kitchen is badly lit, rife with potholes, and full of traffic. It is not the route to independence.

Artists must stop paying these tolls, exit that road, and make their own way. But to do so, they must equip themselves with 21st century machetes: business training, digital tools, a willingness to engage directly with potential collectors, and the self-esteem to drive their curiosity and determination. They must stop trying to proceed within the industry’s existing framework, and stop following the rules. Instead, they must ask a different set of questions at every juncture:

- Why does it work this way?

- Who profits from it?

- What are the true costs and true benefits for me, my business, and my career?

- Am I giving away more than I’m getting back?

Suggest Your Own Rules

I grew up around artists, and I know that they’re constantly being asked to do things that are rarely suggested to other business owners. Too often, they go along with these requests, complying with outrageous terms, because they either don’t know their options, or feel they that don’t have any. As the daughter, wife, and cousin of artists, I know the obstacles they face, but as a business strategist, I view them differently. Here are three examples:

- Take the deduction. If you are asked to donate your work to a charitable auction, suggest instead that you donate the proceeds from the sale of the work to the charity. That way the institution can display the work at the event, and promote its sale, and you can deduct the full sale amount, instead of receiving a tax deduction for only the cost of the materials used to create the piece.

- Get it in writing. Always ask for an agreement. If the gallery, dealer, or museum does not have one, send them one yourself. It doesn’t have to be complicated or long—it just needs to spell out what you are each agreeing to do and not do. If the other party refuses to sign anything, you may still decide to work with them because you’ve determined that the risk is worth the reward, but you will both have learned a lot about each other: you will discover whether or not they are to be trusted, and they will understand that you are a professional who will not be easily or unwittingly exploited.

- Track your collectors. Ask for the names and contact information of anyone who purchases your work. If a dealer won’t give these to you, so be it, but again, you will have learned something about that relationship. Look for a new dealer when you can, and make that transparency part of your agreement with that person.

Here is my cardinal rule: Ask a lot of questions. Ask them of yourself, and of everyone you work with. If you can think of a question, ask it. It never hurts to ask, and negotiating usually raises your stock, even if the other party doesn’t compromise in the end. If something doesn’t make sense to you, it probably doesn’t make sense at all, or else it makes a lot of sense for the other person, but won’t benefit you.

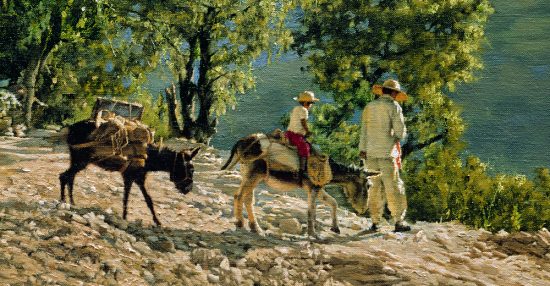

Make Like a Donkey

My father loved donkeys. They were a favorite subject of his to paint, but he also loved everything about them. In particular, he appreciated their stubbornness, which he considered “rare intelligence.” You can back a horse off a cliff; not so a donkey. In business, it’s often wise to emulate the plebeian beast of burden, rather than the aristocratic stallion.

So, don’t make a move until you understand what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and what the short-, medium- and long-term effects will be. The more rushed you feel, the slower you should go. Just because someone else is in a hurry doesn’t mean you need to be. Remember, the objective is to realize your own ambitions, and accomplish your own goals. There are times when you can do that by following in other people’s footsteps, but if you look up and realize that you’re not where you wanted to be—or that you “can’t get there from here”—don’t hesitate to stop, look around, and then strike out on your own.

Great article Elizabeth! I have been approaching most of my artistic career in this fashion especially in the last few years! What I have noticed most is how the artists are getting taken advantage of by museums and art organizations! All of the costs are now becoming the burden of the artist, creating, framing, shipping, etc!! There needs to be more give and take like it was years ago!