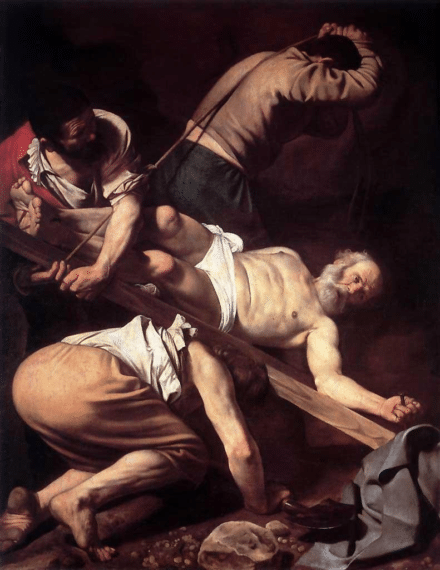

I’ve been thinking about Caravaggio. Actually, he’s been the catalyst for an ongoing discussion with my husband that arose because of a new play he’s been directing that has that artist as its protagonist (see right). Our serial conversation has covered politics, religion, the color red, Thomas Moore and Shakespeare, how to hang a mannequin, Freud, The Knights of St. John, and, of course, ART.

The upshot? Caravaggio’s oeuvre marks a shift in perspective from ideal to real. Therefore, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio = the dawn of Modernism.

An Unimaginative Genius

Caravaggio lived at the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th century. He was a realist, in every sense. He steadfastly examined what was actually in front of his eyes, and it was not often pretty or nice. He painted everyday people and scenarios without cleaning them up, which was completely revolutionary for his time. His contemporaries, on the other hand, used models and idealized the scenes in which they placed them so as to meet the standard code of the day. For his refusal to do this, Caravaggio was labeled “unimaginative.”

The truth, of course, is that he was the one who actually exercised his creativity. Everyone else was following prescribed formulas to create work that would not make anyone too uncomfortable. Caravaggio, on the other hand, showed everything as it truly was—blood, guts, tears and all—and he upset everyone by forcing them not only to acknowledge the world in which they lived, but also to recognize that they might have some responsibility for it. (Luckily, Caravaggio’s technique was so incredible, his work so powerful, and his patrons’ desire to one-up each other so acute, that they overcame their discomfiture and continued to give him commissions.)

From Ideal to Real and Back Again

If you examine the architectural tenets of Modernism, you see it is an inevitable byproduct of Humanism, the ideology that places man- (and woman-!) kind at the center of existence rather than reserve that spot for a divine presence. The roots of Humanism lie in ancient Rome (or, one could even argue, in Classical Greece), but one can point to the Renaissance as the beginning of our current Humanist era, in which we still have one foot firmly planted.

From the Renaissance forward, there has been a slow, consistent progression away from ornamentation and decoration, toward a functional aesthetic that serves our activities. We have made this entire era about us. This can be traced through the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, in every facet of our existence, from the quest for conquest to the quest for human rights. Throughout, art has led the way.

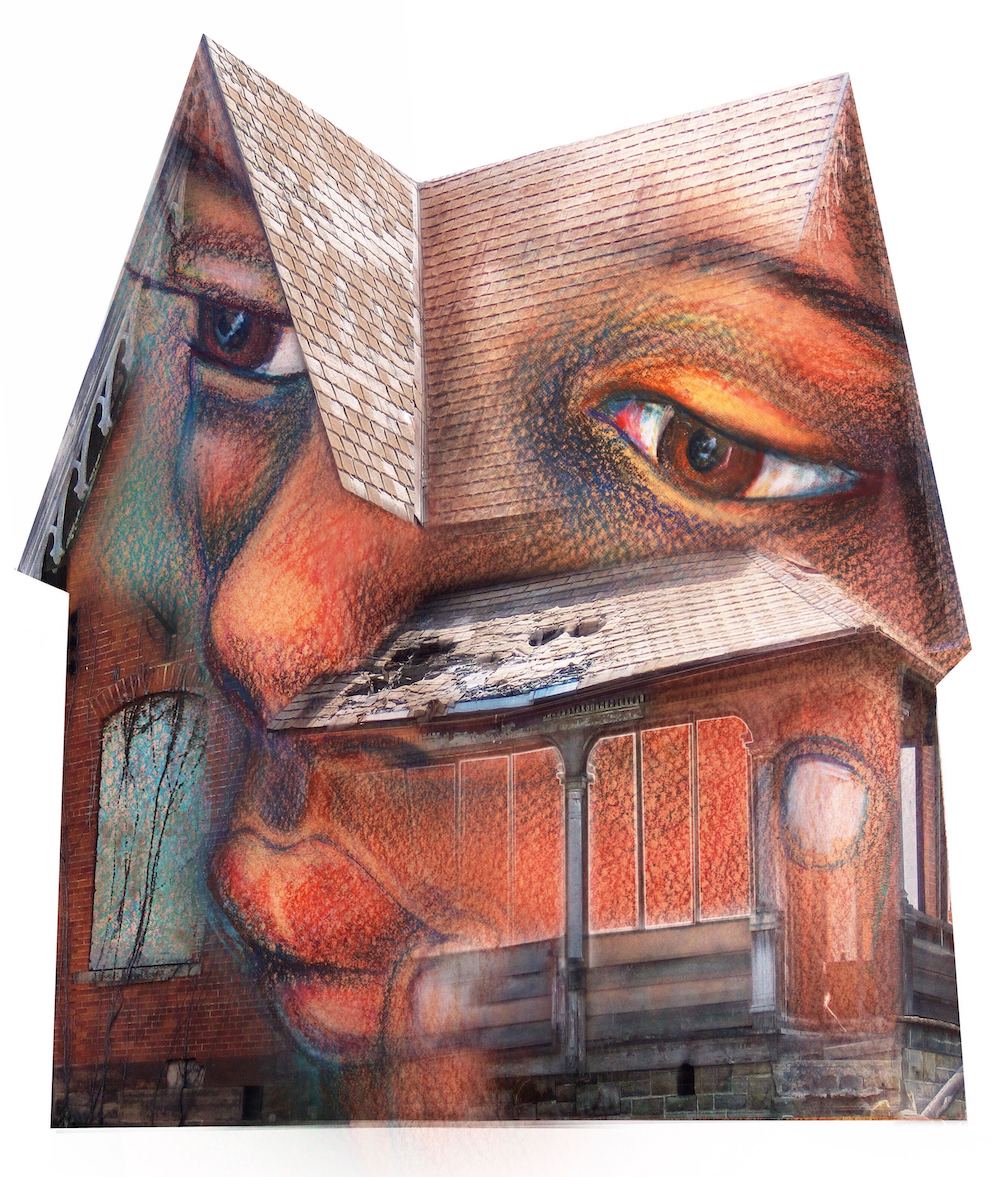

By the time we reach the 20th century, human beings reside squarely at the center of everything, and are striving to create ideally functional surroundings for us. Philosophers and artists are exploring internal landscapes more and more, as we struggle to aestheticize hard science. This culminates with Bauhaus—form + function. It leads to Dalí, Magritte, Miró, and so many others producing internal/external landscapes, and brings us ultimately to the extreme, absolute abstraction that we see everywhere today.

Postmodernism struggles to synthesize all of this. On the one hand, human beings should strive to create perfect functionality in their surroundings, their tools, their lives. On the other hand, we should celebrate the beauty all around us, and strive to respect, preserve, and add to it. This has led to two main aesthetic formulas:

- Aesthetics for aesthetics’ sake: create beauty. This often devolves into formulaic commercial expression. Instead of the Madonna and child, we have those gas-lamp-lit twilights, and sections of works by old masters displayed on designer handbags.

- Art that accomplishes something, that serves a function or comes with a statement

That’s right, these are FORMULAS. We have come full circle and are now avoiding reality, postmodern-style.

Joe and Jane: Lost at the Center of it All

Actual, individual human beings are not represented in the output of these formulas any more than they were when Caravaggio broke the rules. Once again, Average Joe and Average Jane are overlooked in favor of today’s Ideal Joe and Ideal Jane, whose lives are improved through Efficient Design, whose opinions are expressed through Artistic Statement, and whose surroundings and persons are beautified by the Artist and Designer. Average Joe and Average Jane do not get to choose what they like, or what works for them as unique individuals. By failing to support a plurality of voices, opinions, and aesthetics, whether functional or not, we have deprived them (ourselves) of free will.

We make this sacrifice because we still don’t want to face what’s really there in front of us. It makes us uncomfortable and demands our attention and action. Reality cannot be commodified. It just is what it is, and we either have to meet it on its own terms or avoid it altogether by dictating what is acceptable–what is “art.”

Allowing Joe and Jane to exert their personal, singular taste would lead us down a very slippery slope toward noticing what is really there, which would then force us to acknowledge that not everything in our world is ideal or functional or pretty. We’d have to face the fact that we are not at the center of our world, and that we are destroying it with our erroneous sense of entitlement.

This is exactly the message Caravaggio delivered 400 years ago. He faced the truth and captured it in paint, warts and all. Our job as human beings remains the same today: meet reality on its own terms and make our own choices, preferably for the greater good.

Clearly, this job is incredibly difficult because we are still doing everything we can to avoid it. That’s the sane thing to do, right? Caravaggio stared reality in the face, and it killed him at the age of 36 because he couldn’t manage to stare back while living a balanced life. And so we keep that back foot stubbornly planted in Humanism. We (almost universally) acknowledge that the Earth is round and revolves around the sun, but many of us still struggle to accept global warming let alone the strong likelihood that life exists on other planets. Our forward foot is reaching into an unknown ideology where we are but one piece of a gigantic universe—exhilarating, but also terrifying. Much easier to invent whole structures and ways of living with which to mask the truth.

The Impossible, Essential Balancing Act

The life and early death of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio perfectly represents the artist’s conundrum: how to maintain unwavering commitment to your vision and purpose while caring properly for yourself. If you compromise on the vision, or fail to communicate it, you lose your reason for being. If you focus on the vision to the exclusion of everything else, you risk ceasing to exist before articulating it fully, failing to be listened to because you lack empathy, or being misunderstood because your delivery makes your message inaccessible. It’s all a balancing act, one at which this greatest of painters did not excel.

Guess what? This quandary is not reserved for artists. It’s universal. Butchers, bakers, candlestick makers, and every single one of us are up on life’s high wire, whether we want to admit it or not.

A well done, and well thought out essay. Thank you for sharing.

To my mind, most people reject the concept of thinking for themselves. In art, as in life, conforming to rules and conventions makes most people comfortable. Thankfully, there are always a few who dare trust their own minds and instincts.

Thanks so much, Bart, I really appreciate it.

Elizabeth,

Thank you for this timely, powerful article. I am reminded of Frank Stella’s interesting book “Working Space” which also sees Caravaggio as an artistic beacon for our era. Much to think about after reading your thoughts.

Thanks Gregg! You guys are giving me a lot to think about these days, too!

That was beautifully written Elizabeth. And timely as I sit in my shop injured and unable to lift a power tool (so I focus on the writing instead). How to balance the urgency to create it all right now but not burn your body out too soon – I feel a kinship to those who passed so soon.

I specifically appreciate how you worded this – “we should celebrate the beauty all around us, and strive to respect, preserve, and add to it”. That’s what I’ve been wanting to say, but this is much more concise.

These are powerful observations, and if we as a whole embodied that, then our world would be a different place. The results of our actions would have different results for our future as a species.

Thank you for your insights.

Wow. I imagine I will be thinking about this powerful essay for quite a while. ‘The impossible, essential balancing act.’ The idea is both inspiring and daunting at the same time. (And now I want to see your husband’s play, too.)

The timing of your article is charming… Pat is guiding me through my IGP, where the question keeps coming up – what is modernism and post-modernism, and why are these passages of time and/or philosophies central to your proposal? Now I know it’s on his mind too!

It’s a well rounded take you have, looking at the progression towards a functional esthetic. I’m wondering if you distilled your essay by looking at the definitions of modernism and post-modernism according to philosophy or art?

I always use 1890 as a nice (over simplified) benchmark for the beginning of Modern art. You could say both psychology and sociology were “invented” around then… the idea that we have a mind and a place in society brought incredible paradigm shifts. Manet’s bar-maid is exactly that, and the timing was also in alignment. The viewer is forced to ask the question, “is she happy? does she want to be there?”. The answer is clearly not. Despite her place in society as prostitute and servant, the man in the top-hat asking her fee (you, the viewer) asks for the first time ever, these questions about her situation, and not selfishly his own. Until then everyone had their place in society and it was fixed. God kicked the pope, the pope kicked the priest, the priest kicked the husband, husband kicked the wife, wife kicked the child. This power structure was taken for granted. Never questioned.

With modern thinking, modern humanism, our culture planted the seeds to become truly compassionate. This spurred on feminism, multiculturalism, etc… until we became so aware of ourselves in relation to others, we could no longer quantify our progress – looking at other cultures broke down the concept of a linear path of evolution.

Caravaggio was beyond his time, painting and pushing along a philosophical evolution.

There are a million ways to look at these movements. Thank you for this interesting and wonderful angle!

Thanks Willy. My training is in history and social science, so my perspective on this was historical. I know I’ve mashed together different views on Modernism and etc. Was trying to back up and see the gigantic, multi-century arc that began in the 15th Century and which I am arguing is ever so slowly drawing to a close.

It’s a fascinating topic, and yes it is drawing to a close. I’m currently reading Kuspit’s “The End of Art”. He would say the arc of esthetics, beauty and even art as first-hand experience is coming to an end. He’s not a pessimist, but he doesn’t paint a pretty picture.

I personally see the possibility of regenerative growth, like a forest fire clearing out brush for new growth. I wouldn’t want to be too much of an optimist either though.

Your article is balanced.

Hi Elizabeth,

I was especially engaged by the last chapter….all of it. Staying true to my vision is so essential, consuming and rewarding . Each painting is a further liberation from conformity and hopefully closer to what’s universal which can be experienced by anyone or none. I am very grateful to have come this far and your article helps me down that path even more. Thanks for writing it! Peter S.

BTW I forgot to mention when I was fortunate to spend my junior year in Rome I would often go into the twin churches in the Piazza del Popolo where Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of St. Peter and the Conversion of St Paul were hung. So fortunate to have felt their power. My aim has always been to achieve that power in abstract expressionism…..or another ideal is Van Gogh’s emotional power!! Thanks again for the article Elizabeth.