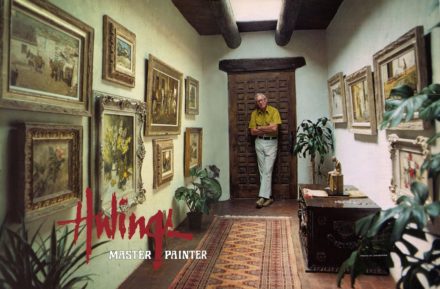

Clark Hulings wanted to do specific things with his visual art. To succeed, he knew he had to be commercially successful, but that he couldn’t let others determine the shape of his career. It was on him to make his own blueprint for what he wanted.

Career Blueprint

Hulings would never settle when it came to his own career vision.

Rejecting the myth that it’s always one or the other–follow your muse and make art on your own terms or be successful commercially–Hulings set out to do both, and succeeded in becoming a seminal American artist.

Hulings resolutely rejected dependency, never ceding control of his own career. Case in point: he operated 23 years without a gallery, because he didn’t know he could sell the work without giving a cut. He hired people to help, and he formed specific relationships with exhibitors (for groups shows, etc) to increase his exposure. He built his career on his own terms and, when working with a gallery did make sense as the next logical step, he did that on his own terms as well.

Of course, Hulings did not always have the leverage or power he achieved later in his career, and certainly most visual artists won’t have it from the get-go. However, the mindset and confidence Clark Hulings exhibited had to be there all the way through, because that’s what enables any artist to reach the level He did.

Likewise, while there’s no template for artistic vision, Hulings defined one for art entrepreneurship. Hulings took seriously a core set of practice areas that continues to guide working artists in becoming self-sustaining entrepreneurs.

Sales and Selling

Hulings embraced sales and selling, even if reluctantly.

Hulings hated the duty of going to parties and the business of hobnobbing. He actually wanted to be left alone in the studio to paint, but he understood the value of hand-to-hand combat—of in-person relationship selling. He would go out to lunch four days a week, and he and his wife Mary would host up to three dinner parties a week. He would get dressed and drag himself to a party and, an hour or two later, his family would be ready to leave but couldn’t find him. Invariably, he was in the middle of a crowd, occupying the limelight, and they’d have to drag him home, where he would complain about so much time wasted not painting!

Hulings allowed himself to be interviewed by society pages, because knew he had to have a public persona, but it was always exactly who he was. He didn’t really want to “sell” and manage his brand, but he was willing to do the work and secretly enjoyed being social. He would knock off of work and do all that social stuff, because knew it was essential and he was good at it. Hulings understood the need to embrace society instead of working in a vacuum, and to let society embrace him as well. And they did.

Likewise, Hulings updated his business model repeatedly to stay ahead of the curve. He carefully observed the market shifting and took advantage. He saw art auctions as the next big thing. That was revolutionary in the 1990s. He forged direct, early relationships with various auction houses, and was one of the first artists to put his own art up for auction.

Financial and Market Strategy

Hulings made the most of his market and maximized sales negotiations or future profitability.

Hulings created ancillary products. If he knew someone was interested in a large piece, he’d create a smaller version of it after the fact and get them to buy both! He called the smaller versions “models” since they were not done to help him work out the details for the major work. Of course, sometimes he did create “working models” or “sketches,” and he would market those the same way.

He negotiated with dealers, wheeling and dealing not just on the commission or whether they held a show of his work every year, but also on the amount of time they’d commit in writing to display the work on their walls—e.g., they might not be allowed to sell the work until it had been displayed for thirty days, etc. They couldn’t keep it in the back bin, either. Hulings wanted visibility and exposure. He was willing to pay collaboratively for advertising, catalogs, etc. If someone wanted an exclusive, he’d insist they make it worth his while. Otherwise (of course), he was going to work with other people and sell things at auction.

In the 1990s, when Clark Hulings decided to go after more exposure, he finally established a new gallery relationship. For Hulings, it made strategic sense as a promotional step. Rather than buy his own advertisements or hire his own publicist, he would extend the functionality of his business through outsourcing. He partnered with a gallery that had those functions built-in. That move wasn’t made out of desperation to get sales, but precisely because he was so successful, so he had the leverage to do it on his own terms.

The financials made sense, too. He cut a deal for 80/20 in his favor (the average is 50/50), and he agreed to split advertising costs. Built into the agreement was a minimum required amount of advertising and promotional activities to be undertaken by the gallery. The shift to galleries was strategic and maintained Hulings, as the artist, at the center of the relationship.

Hulings treated his business like a business. He kept detailed sales logs going back to 1960 and a ledger with columns containing a code for gallery, venue or method of sale, title of painting, dimensions, date delivered to venue, date sold, gross price, and net dollar value to the artist. This included paintings, drawings, book covers, among other things (like music-album covers). He also kept detailed contact sheets (before the Rolodex or CRM) for ongoing account management around all his correspondence.

Brand Story

Hulings understood his own brand story, even on occasions when his audience didn’t.

Hulings deliberately targeted the Western art market. He wanted collectors to go to the National Academy of Western Art and buy a painting of France, without seeing any contradiction (perhaps without even thinking about it). He intentionally relied on our cognitive dissonance and suspension of disbelief. He wanted multiple markets and was always aware of his target audience. Like Liberace, he knew how to “give the people what they want.” He would let the customer say what they believed, and the emphasis and theme in Hulings’ narrative shifted, depending on the particular customer to whom he was responding.

Hulings was both pragmatic and creative. He was always clear on how far he’d go to meet the customer and what line he wouldn’t cross. When the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum started (as The Cowboy Hall of Fame and Museum) with a group show, he very deliberately thought about what he could paint, not being a “Western” artist. He decided to do the Grand Canyon, a common setting, but added figures—which was not the norm. It was extremely rare to see any Hulings work without a figure, because his entire brand was humanity on the planet. There was always a protagonist, and the protagonist is us. He would force the viewer to experience reality vicariously. Also, he painted the canyon covered in snow because that would showcase his particular abilities. Almost nobody did that, because it was too hard, but Hulings challenged himself to differentiate himself.

Hulings was in constant negotiation with Dean Krakel, who ran the Cowboy Hall, about what works he’d show. Hulings got Krakel to include in the museum’s purview the 17 states West of the Mississippi, including Louisiana. Following that, his argument was then simply a slippery slope: Don’t you have to acknowledge that many of those states used to be Mexico, so why not include Mexico? Mexico was what he wanted to paint. That eventually led to including Central America.

Networks and Collaboration

Hulings leveraged a network of peers to advance the business of art.

Hulings was an organizer who participated in peer networks and collaborated with other artists to collectively determine their market and advocate to keep artists at the center.

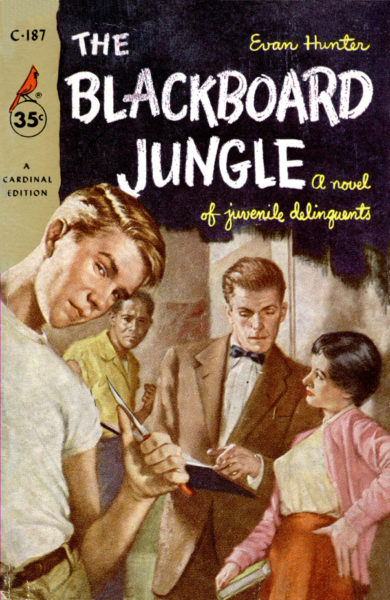

One of the publishing houses hired a toxic marketing director. The illustrators didn’t really work for her—in most cases, they worked for the art director—but this person would inject needless and counterproductive demands into the process. So Hulings rallied the illustrators, who banded together to oust her. They wrote to the art director and demanded that they have nothing more to do with her or they’d all quit. The artists won, and the publisher moved the interloper to a different part of the company.

Hulings was also one of many who got together and collectively advocated to change the tax laws. At the time, inheritance tax on art was at full market value rather than the value of materials used or a percentage of market value. This was particularly onerous if the artist donated the work, because the corresponding allowable tax deduction was only for the cost of materials used to create it.

Under current tax law, artists making charitable donations of their work are allowed a deduction equal only to the cost of the materials used. Art collectors, however, may take a deduction equal to the fair market value of any piece donated. Exacerbating this inequitable situation is the fact that an artist’s estate is taxed on the fair market value, rather than material cost, of a network still in his possession at the time of his death. – Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol 37, Issue 3 (1987), Article by Douglas J. Bell

Artists with terminal diseases would actually burn their art to avoid bankrupting their estates. Combatting this was a huge undertaking in the 1970s by thousands of artists all over the United States, writing letters, calling congresspeople, and lobbying to get the tax laws changed. Hulings was instrumental—encouraging every artist he knew to get involved.

A Technical Toolset

Hulings utilized every relevant or useful technology to increase his productivity.

Hulings made use of photography at the beginning of his career but constantly experimented with other technologies for his “recipe-method” of constructing scenes. When Photoshop emerged, he jumped on it for the efficiency. The business person in Hulings said to the artist, “You can turn out more work, faster, more efficiently, without negatively impacting the product.” This is one reason CHF Excecutive Fellow Blake Conroy turned to laser-cutting. “If I could get the same precision by hand with the same efficiency, I would. The technology lets me get exactly what I want, and does it faster.”

The CHF Mission and Model

The Clark Hulings Foundation is the product of Hulings’ own leadership and example in artist entrepreneurship. CHF’s educational programs utilize the very practice areas that were key to Hulings’ own success, including: Sales Strategy, Financial Competence, Marketing from the Brand Narrative, Technology, and Peer Networks. Fellows in CHF’s Business Accelerator Program acquire these skill sets, as well as legal and logistics learning, and create a pivotal project to advance their careers according to their own unique Career Blueprint.

Clark Hulings was an art entrepreneur par excellence. His art continues to inspire generations of artists, figurative and otherwise. His entrepreneurship shows not only what is possible, but how it can be achieved. This is why The Clark Hulings Foundation for Visual Artists exists. It is not merely a tribute to Hulings’ legacy, but the ongoing practical vehicle for ensuring generations of working artists become thriving artists.

To take advantage of CHF’s programs—its Digital Learning Portal, Business Accelerator Fellowship, Art Business Summit events, and The Artist Federation network of professional artists, visit the menu at the top of the CHF website [clarkhulingsfoundation.org] and decide on your next steps for taking powerful charge of your career.