A member of CHF’s Advisory Board and a judge for our grant-review panel, Watie White is a painter and printmaker based in Omaha, Nebraska. In addition to his pieces that have appeared in museums and galleries, he has created many public works, particularly in underserved communities, collaborating with local people and reflecting their stories in his art. He is also on the board of directors of the Omaha Creative Institute, and is actively involved with that organization’s Artist INC program, which supports the professional development of local artists.

A member of CHF’s Advisory Board and a judge for our grant-review panel, Watie White is a painter and printmaker based in Omaha, Nebraska. In addition to his pieces that have appeared in museums and galleries, he has created many public works, particularly in underserved communities, collaborating with local people and reflecting their stories in his art. He is also on the board of directors of the Omaha Creative Institute, and is actively involved with that organization’s Artist INC program, which supports the professional development of local artists.

In a recent interview with CHF Editorial Director Sofia Perez, Watie discussed the value of building a strong artistic community—a holistic “art ecosystem” as he dubbed it—and the need for artists be as inventive in the way they manage their businesses as they are when creating their art.

SP: Tell us about your work with Artist INC, which shares some of the same goals as CHF’s Business Accelerator Program.

“…the things I want to do have to benefit everyone involved, and that includes me.”

WW: Participating artists go through an eight-week course where they learn about things like marketing and business planning. In addition to being part of a larger group that attends lectures, they also work in smaller groups, which are led by a mentor—someone who has some additional knowledge—and [the Omaha Creative Institute] asked me to take on that role. But those of us who serve as mentors are not so distant from where the artists in the program currently find themselves.

SP: Why is mentoring important to you, and what have you learned from it?

WW: To be honest, I am a little bit uncomfortable talking about the role I play where I have some sort of assumed authority. I seek people out because I want to be around good art. I mentor people because I want them to be better than me, because I want someone to show me some great things.

Similarly, when I work in communities that are economically depressed or socially isolated, I’m doing it for selfish reasons. I do projects in these communities because those are the great stories. They’re ordinary stories, but they’re very powerful, and they selfishly allow me to get to make art that I would never be able to make otherwise. Although it’s also true that I want everyone to leave their interactions with me feeling like they got more than they gave.

It took me a long time to come around to the idea that the things I want to do have to benefit everyone involved, and that includes me. I have a few public projects coming up this summer, and I’m actively fundraising for them—applying for grants, etc. In working through that process, I know that I’m going to do the project anyway, and I know I’m going to get paid last, but I also know that if I don’t get paid, I will not be able to do another project again. If I can’t find a way to make it sustainable, it won’t last, and it won’t be replicated. It’s good when a one-off project happens, but it won’t have nearly the impact you want, unless you can program it well, return to it, and build off it for the next one. Then you start a larger conversation that connects more people to it.

SP: So the way you manage the business side can impact the art you produce?

WW: Exactly. I used to serve as the director of a family foundation, and I’ve been on a lot of boards, overseeing grants. I’ve also applied for a lot of grants as an individual artist. The application process is often full of bureaucratic questions that appear dumb or irrelevant, and it’s annoying to fill out the forms, but when I actually consider the questions, more often than not I realize they’re there for a reason.

By taking the questions seriously, and answering what they’re asking you in the most thoughtful way possible, not only do you wind up making your application much stronger, but you also make your own project much stronger. I was often asked questions that I wasn’t asking of myself in the same way. By considering those questions, it caused me to change my kind of engagement—to change the ways I defined who the project was for. All of that helped me figure out how to do a better job of communicating about it, rather than assuming everyone would get what I was doing.

SP: Visual artists can be incredibly creative in their work, but many struggle with applying that same creativity to their career planning. Why do you think that is?

WW: There is something very powerful about the “art star” role—the idea that you are going to be discovered by someone who will sell your work, that you’ll become famous, and your genius will be unearthed. It feeds into the rampant ego of all artists, as well as the irrational hope that someone will take care of the money part for you.

When I was starting out in my mid-20s, there were three paths I saw. One was the gallery star. Two was the academic route, where you get your MFA, teach for 50 hours a week, and wind up not making any work, so then you get fired because you’re not showing enough work. And path number three is going on the craft-fair circuit, where you make bad art that you can sell cheaply, and you work really hard on that for nine months, so that you can have three months to do the stuff that’s meaningful to you—but at least you’re working for yourself.

When I mentor people, I tell them they shouldn’t have all their eggs in one basket; they should have multiple income streams. A lot of my public work grew out of not having other local ways of making work that didn’t involve me becoming overly commercial. But with a different, messier path, it can be hard to know what it is. Maybe it’s teach a little bit, show a little bit, apply for public art projects a lot, apply for grants, and keep your eyes open. I’m not an expert in any of these realms, so this approach pairs well with my skill set and interests—and with my bootstrapping-entrepreneur mentality.

SP: You’ve been able to forge a career out of many separate pieces.

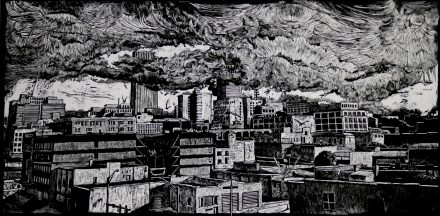

WW: I work in multiple media, but the ideas are often connected in my head at least, even if it’s not immediately apparent to everyone else. If someone who is interested in my public work comes to my studio, and purchases a large woodcut, that purchase is supporting my public work. These things aren’t separated. If you support the production of my studio, you’re supporting all of the production of my studio. If there are some things that work better than others for you, I’m just glad it’s working for you. So it’s a very holistic thing.

Which is something that comes up with Artist INC a lot. You’ve just spent an hour talking about accounting or something, and you wind up having conversations about their personal life—about what’s going in their world that is helping or inhibiting them. It’s easy to feel that those things are not relevant to the overall work, or to what’s going to make you better as an artist or as a business owner. But you have to take seriously all the random things that are in someone’s life, and read those things for clues. If someone can’t stop talking about meaningless stuff, then that’s what you have to address in order to get to the point where they can deal with their finances or other matters. We rely on the collective wisdom of our peers.

SP: When you were interviewed on CHF’s Thriving Artists Podcast last year, you said that art is an expression of who you believe yourself to be, as well as a way of discovering that. Let’s shift that a bit: What have you discovered about yourself as the result of how you handle your art business?

WW: I’m someone who is old enough to be considered an adult but can’t believe people are taking me seriously as an adult. I don’t know the answers to a lot of things, but I will give as much effort as I can. The biggest challenge has been to accept that there aren’t real answers—life isn’t simple like that. If you work at it, and keep coming back to it, you get good at things. I still feel like I’m 25, but in talking with other artists or community members, I find that I’m faking it less and less.

I’ve been working full time as an artist for about 20 years now, and for the vast majority of it, I was trying to get better as quickly as I could. Mostly, I focused on things that I wasn’t doing well or that hadn’t worked out, and tried to weave some kind of lesson from that, and not do that thing again. Now there’s been a shift, and I get less and less out of that process. I have started to let myself be driven by more positive things, by doing things that feel good to me, and that I can tell feel good to other people as well.

It took a long time to let go of wanting to be impressive or respected in a certain way, and to realize that people were going to form their opinions of me regardless of what I did. My wanting it so badly was keeping me from accessing the rich storytelling function that would make my work better. It was about getting out of my own way. And taking yes for an answer every once in a while.

CHF provides a platform for artists and industry leaders to share knowledge and expertise. Help us continue to provide this valuable resource by supporting our work.