How are sales impacted by anti-establishment content? Kirsten Stolle is a visual artist whose work examines themes of corporate propaganda, greenwashing, environmental politics and surveillance. Her ongoing project Genetically Commodified includes drawing, installation and sound to probe the consequences of GMOs in the food supply. In this interview with CHF, Kirsten explains the business side of her art practice and touches on a perennial issue for working artists—how to operate so the work comes first.

Is your goal to make a living from your art?

For me, it’s essential to build a sustainable art practice, one that supports my work and offers stability in my day-to-day living. Depending on the time of year and exhibition schedule, the majority of my income may come from art sales. At other times, sales from artwork become less prominent and more of my income is generated from a mix of artist grants, residencies, lecture fees, commissions, artist honorariums and institutional support. Balancing my time, energy and resources is paramount in creating a thriving studio environment and a healthy life. This is not to say, as a working studio artist, there have not been difficult and challenging times. But if I have created a strong infrastructure to support my practice, the downtimes are less impactful.

With art that has a so-called challenging theme, how is it marketed? Does this add another component to the sales process?

The word ‘challenging’ can be viewed through so many different lenses, so I can only speak about my own work. In regards to the themes I explore (corporate greenwashing and propaganda, environmental politics, and industrial food production), I seek out organizations that embrace innovative and conceptually rigorous work. I have partnered with regional contemporary art museums and non-profit spaces, as well as forward-thinking commercial galleries that have a particular focus on creating meaningful exchanges through art.

As sales are not generally part of a museum’s mission, marketing is geared toward promoting the artist’s work on display, garnering critical press, and ultimately adding to artist’s career development. On the commercial gallery front, dealers reach out to curators, collectors, and press that may have an interest in the work based on subject matter or curatorial concerns.

As sales are not generally part of a museum’s mission, marketing is geared toward promoting the artist’s work on display, garnering critical press, and ultimately adding to artist’s career development. On the commercial gallery front, dealers reach out to curators, collectors, and press that may have an interest in the work based on subject matter or curatorial concerns.

What changes have you seen in the way your art is marketed and sold?

With the socio-political nature of my work, I have found a broadening of both the scope and reach of many of my projects. This translates into more opportunities to show in alternative and international venues, as well as having my work connect to a wider, sometimes non-traditional audience.

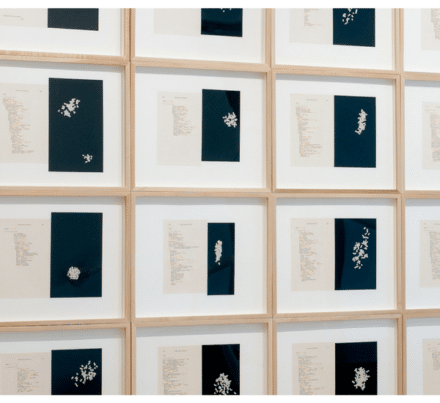

For example, in 2016, The Cambridge School of Weston, an alternative high school, featured my work on surveillance (de-identified) in a group exhibition exploring dystopic societies. My Monsanto Intervention collages are currently included in Evidentiary Realism, a timely exhibition in Berlin examining disinformation and truth-telling. And my recent exhibition at Tracey Morgan Gallery, What Goes on Here, showcases three bodies of work highlighting the historical legacy of chemical companies on our food supply.

It sounds like you work on a project basis, after significant research—how does an artist who moves from project to project approach funding?

The work comes first, and I seek out opportunities that will enable me to push the work forward. (Granted, I don’t work in cost-prohibitive materials like bronze or develop public art projects, where initial capital outlay can be quite daunting). In my studio, I have a notebook where I record ideas, research notes, and sketches for potential projects and future areas of research. Generally, when I embark on a new project, I focus on the research and development of the work, followed by a broad list of venues and thoughts on how to secure funding to realize an exhibition. It is important to find the best fit for the project, whether it be a gallery, museum or unconventional space. If I want to develop a project that requires additional resources or significant upfront investment, I will pursue granting organizations or institutions that offer larger funding opportunities.

What does a working artist need to succeed?

Each working artist approaches their practice in an individual way—no two artists have the same demands, responsibilities, time constraints, financial apparatus or aspirations. It’s really about determining how you work best and most creatively. Are you a morning person? Do you like to block out an entire weekend or work every day in the studio? Do you work in the studio at night, to allow for a day job? Each studio practice is a very focused, individualized ecosystem, one that is tailored to the specific needs of the artist.

If I am shooting high, I would secure funding to hire an administrative person to deal with all the tedious, but necessary parts of my business (inventory, emailing, website maintenance, artwork documentation, contact database, letter writing and tax prep). That would free up energy to spend uninterrupted time working in the studio, experimenting, researching, and developing new work.

All images from are from the What Goes On Here exhibit at Tracey Morgan Gallery. Source: http://kirstenstolle.com/what-goes-on-here/