CHF’s 2017 Business Accelerator has kicked into high gear, and as we get to know our new class of Fellows better, we are learning more about their experiences in the industry and seeing firsthand how those experiences have shaped their professional trajectories. Everything we’ve heard confirms how crucial our work is. To a person, these Fellows are accomplished hardworking artists well into their careers, but they are still desperate for the knowledge and support we are offering, because they have not gotten it elsewhere. In a recent interview, CHF Director Elizabeth Hulings talked to our editorial director, Sofia Perez, about the tangible and intangible impacts of business training.

SP: All entrepreneurs have to overcome certain hurdles when growing their businesses. What are some of the unique challenges artists face?

EH: There are a lot of entrepreneurs who went to liberal arts schools, and then went out into the business world and worked for other people or corporations or in retail before striking out on their own. Some artists have had a path like that.

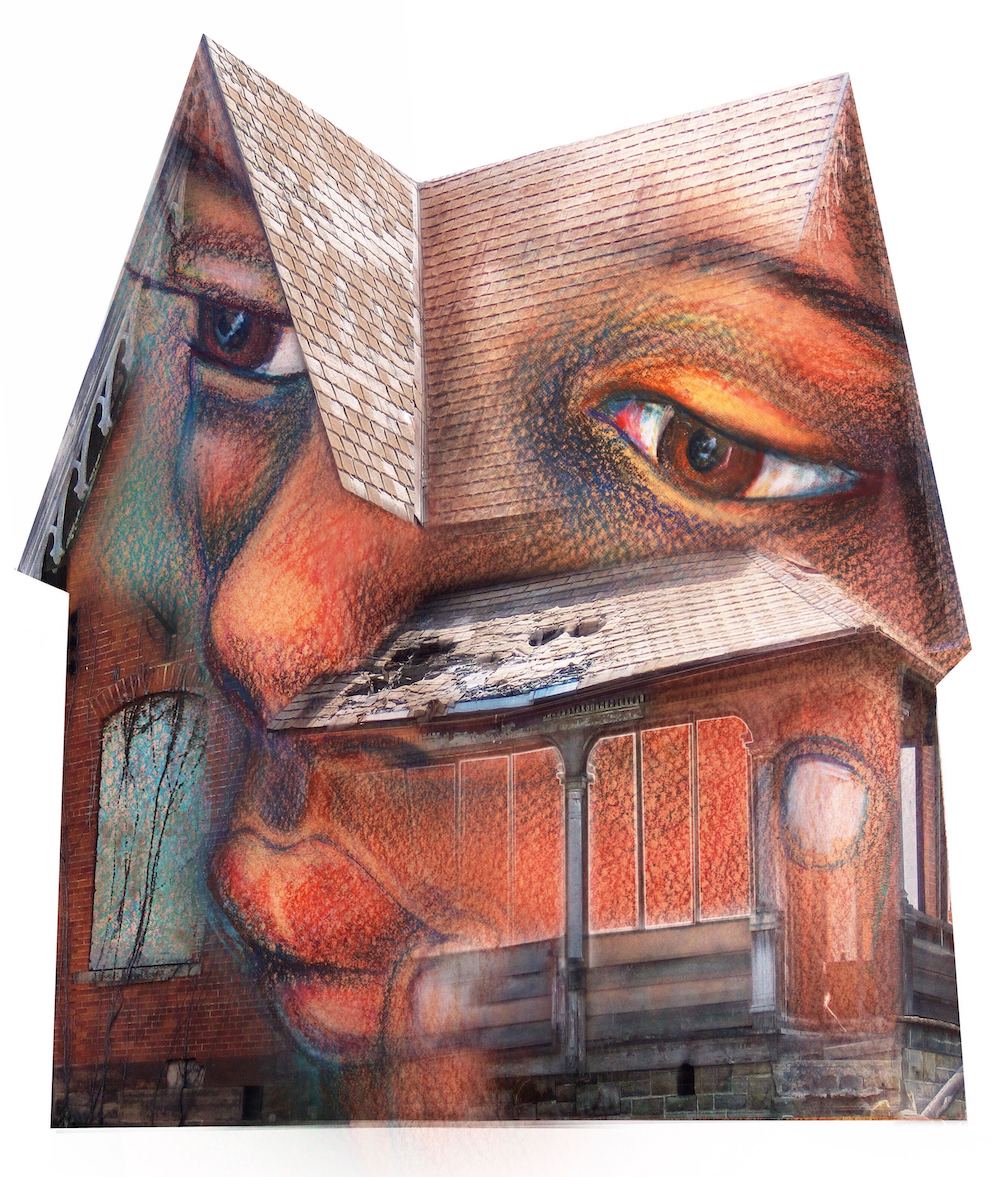

Look at someone like Robert Jackson. He had an entirely different career before becoming an artist–he was an engineer first. There are a lot of people who start out elsewhere and then, interestingly enough, they pivot and say: “I need to work on my art. I need to express what’s inside of me, and this job at XYZ company isn’t allowing me to do that.” So they take the big leap.

These folks have all of that business and corporate experience behind them, and oftentimes they also have some savings, because they’ve been working in a corporation for a while. So they have two things going for them: they have a safety net, and they also have their own personal track record, which they accrued by being in the business world. They know how to speak the language and they know how things get done. And in those cases when they don’t know how to do something, they know they’ll be able to figure it out.

As someone who’s worked in pretty much every kind of business configuration there is, I can tell you that you learn from experience more than anything else. And that experience helps you feel comfortable. The first time you go to a cocktail party, you don’t know what you’re doing. The second time, you think, “Well I’ve been here before, so at least there’s that.” And so, consequently, many artists who have that kind of trajectory go on to be successful. Like Bob Jackson.

SP: Look no further than Clark Hulings, our organization’s namesake.

“…you have to be willing to stand up and say, ‘I am a fully functioning person using both sides of my brain, and I am capable of making decisions about all of this’…”

EH: That’s right; my father is another great example. Here’s somebody who was forced into a career that he hated, in physics, and by his own account, he wasn’t any good at it. But he worked at a laboratory and grew to understand how that world functioned. Then, later on, he became a commercial illustrator. Although he was working in publishing for art directors who often took gross advantage of independent artists, he was still within a corporate framework, so he learned how to deal with the 401(k), submit expenses, deal with the marketing manager, and handle the many other people and things that you encounter if you’re inside a company. Even if you’re freelance, you’re still interacting on a daily basis with a lot of different business entities and business people.

When my father eventually struck out on his own, he had acquired the confidence that came with learning how to do all of that stuff, so of course he could go into a gallery, which is just a different kind of business, and have the necessary conversations. If he could deal with art directors and publishing companies, then surely he could deal with that gallery guy. And he could sign that contract–or not sign it–because a contract is a contract. You have business contracts with lots of people, and they are going to try to swing them to their advantage, but at least you know the lay of the land, and you’re not nervous about it.

SP: And what about artists who’ve had a different trajectory?

EH: Many artists start out knowing that art is what they’re destined to do. While it’s great that they have such certainty, they don’t have the other advantages I just mentioned. And nowhere along their path is it easy to acquire them. Art schools don’t teach these things, and business schools aren’t geared toward artists. Many artists who start out directly pursuing art careers end up teaching, which puts them in another universe altogether.

Academia is entirely different. Although a lot of academicians face similar challenges. They realize mid-career that they’ve had enough of that world and want to do something else. What they often hear is, “You’re a professor. You don’t know how to do business.”

So every silo protects itself from interlopers. It happens across the board. In the end, it’s all about building up a range of experiences that enable you to feel confident in whatever environment you choose.

SP: And that confidence is crucial, but it’s often beaten out of artists for calculated reasons.

EH: Take the analogy of buying a car. There’s no set price, so when you enter a dealership, their entire goal is to throw you off-kilter, to put you in an insecure psychological state so that they can gain the advantage. Oftentimes, the result is that you don’t push for the right price, and you end up paying more than you should.

We also saw it with the mortgage situation prior to 2008. A lot of people were buying homes and applying for interest-only mortgages. Many of those first-time buyers were preyed upon, and they were not equipped to sort through those agreements. Why? Well, that’s a much larger question about our educational system, but the fact is, there was a deficit of knowledge and experience there, and the lender was willing to exploit it. Similar things happen in the art world.

Artists don’t tend to come in with a strong business background or the confidence that comes from that kind of experience. Right from the beginning, they’re at a disadvantage, and there are people in the industry who exploit that.

Also, historically, artists have been easier prey than others. Beyond the reasons I mentioned, there’s this additional weapon that gets used against them: the right-brain-left-brain conundrum, the idea that artists only use their right brains. And people also apply a version of it to scientists: “They only use their left brain.” All of that is garbage. I mean some people use their brains better than others, but everybody uses both sides, at least a little bit.

SP: It’s insulting all around, a) because it implies that people who aren’t artists are not creative, and b) because it becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy for artists. Their lack of confidence forces them to rely more on others, which digs them into an ever-deeper hole.

EH: Exactly. I live in a co-op building in New York City, and we were discussing what to do about our lobby, which needed renovating. The board established a decorating committee that included a human resources professional. One day, he announced to the rest of the group that two of the other committee members–a photographer and a stage director–shouldn’t be involved in the vetting of the designer we’d be hiring because these folks were “just creatives,” and creatives don’t know how to manage things. Which of course is ridiculous. This human resources guy was a middleman at a big company. Beyond a few subordinates and department heads for whom he has to find staff, he’s not managing ANYBODY. Meanwhile, the photographer has to contend simultaneously with editors, journalists, and subjects; that’s managing up, down and lateral simultaneously. And the stage director routinely vets and manages designers, and that’s on top of corralling 75 people who are all moving around in the theater at once and telling him that he can’t do what he’s doing because the conductor is in charge, or because the soprano can’t work that way, or the elephant is on break. That’s a massive management operation. But he’s a “creative.”

In this society, we’ve moved from using “artist” as a dirty word to the label of “creative,” and it’s applied more broadly to undercut an even bigger group of professionals. It creates a stigma and implies that we should applaud you, the creative person, just for finding your way to the meeting, for tying your shoes and not tripping over yourself, and for getting yourself dressed and fed, because the only thing you’re good at is staying in your studio and creating something in a vacuum. Naturally, this is followed by a pat on the head. “Don’t worry about the legalities of this contract, or the commission percentage, or how things are going to get shipped and moved, or who’s buying your work. That’s MY job.” What that does is take ALL of the power away from the artist, and put it in the hands of the other person. It’s a recipe for exploitation.

SP: And sometimes they even try to dictate the artist’s actual output. Artists are told what kind of art they should and should not create, because “XYZ won’t sell.”

“…If I’ve been able to figure out how to apply 3D-printing technology to my sculpture practice, then I can probably figure out how to use Instagram…”

EH: It’s like the car-buying example I gave earlier. “You don’t want the soft top on that Jeep because it isn’t any good in inclement weather. Oh, but you really like it? Hmm, so maybe you’re going to have to get both.” It’s an upsell. In that moment, the person isn’t quite sure, so you take advantage of that uncertainty.

It happens with regard to genre, subject matter, style, size, etc. The art dealer, the advisor–they want to seize control of that dialogue, just like the guy who is selling you the car. It’s not like HE made the car. He didn’t have anything to do with that. He’s just trying to exploit the situation and get a bigger commission.

To be clear, I’m not saying all dealers are like this, and I’m not saying all advisors are either. I’m just saying that the industry has been established in such a way that makes it easy for opportunists to take advantage of artists, because it’s the only edge they’ve got.

They’re not creating the product; all they can do is try to control it, from its actual creation all the way through to the sale and resale. It’s a transactional business. The more they control, the more money they’re going to make, and the more prestige they’re going to have for themselves. If you’re an individual who gets a percentage from each transaction, transactions are what you’re going to pursue.

SP: Where do things stand in today’s art industry? Is the balance of power shifting?

EH: Everything on our planet is shifting. We’ve created all kinds of new technologies and ways of doing things that are causing major shifts in this industry. The Internet has changed everything for everybody. Look at publishing. Look at music. You download your music now. You don’t buy whole albums–you download song by song. And who’s in charge of that? That’s a whole other can of worms. With regard to visual art, it is still possible to control the original product, which you can’t do as easily in music. But it’s still a question of who has control.

Because of all the technological shifts, artists have an opportunity to better control their own product; it’s easier than ever before for them to affect these transactions directly. But they have to seize the day NOW. They have to say to that dealer, “I want to know who bought my work. I want that person’s contact information, and I am going to keep track of them myself.” That’s a huge statement of empowerment, and dealers won’t want to hear that. They don’t want to give that up, because if the artist goes directly to the client, they don’t make any money.

However, along with the opportunity comes the challenge of having to deal with copyright and intellectual property, and that cuts across every sector of our society and every artistic industry. It’s very tricky, and you have to be willing to stand up and say, “I am a fully functioning person using both sides of my brain, and I am capable of making decisions about all of this. I’m going to let people put low-res images of my work all over Pinterest, and share it there because that’s free marketing for me. But I’m going to make sure that nobody posts high-res images anywhere.” You want to prevent them from printing it life-size and hanging it on a wall or whatever. It’s about empowering yourself and saying, “I’m capable of figuring this stuff out. I’m capable of managing it myself–or managing the person I hire to do it.”

SP: It’s an enormous opportunity, but artists have to have the tools and knowledge to seize it.

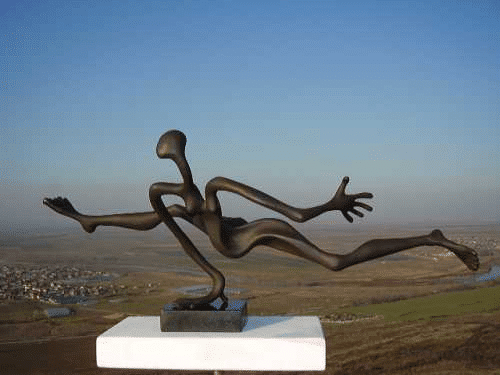

EH: Right. The irony in all of this is that artists are better equipped to seize this opportunity than many other people who’ve just learned how to do specific jobs. Artists look at the world and take advantage of everything they encounter, and they use it to express themselves. There’s no issue with retraining or learning all kinds of new stuff because artists do that all the time anyway. It’s just a matter of getting them to realize it. “If I’ve been able to figure out how to apply 3D-printing technology to my sculpture practice, then I can probably figure out how to use Instagram.”

SP: So, in the end, it comes back to building their confidence.

“…You don’t have to do everything yourself, but you need to be directing it, because only you know why you created that thing…”

EH: The biggest thing to remember is that the people who have traditionally managed an artist’s career–the ones who dealt with sales and marketing so that those poor little things didn’t have to tax their left brains–THOSE folks don’t know how to deal with these technological shifts either. It’s ALL new for everyone. So when someone says, “You shouldn’t be doing that. You should be in your studio creating, and I’ll manage all of this for you,” at the very least, the artist should ask, “Why? Have you done it before? What’s your expertise?” Nine times out of ten, that person doesn’t know what they’re doing either.

They’re not Duveen. He was an absolute opportunist, but let’s face it, he was brilliant at it. So as an artist, you get the commission and then you turn the other way because you don’t want to know what he’s actually done, but you know there’s a reason for putting that guy in charge of selling your art. But these days, you look around and think, “What’s that guy really going to do for me? Does he really understand my work, my collectors, and my market? And does he really know how to go out and find them? Or is he just going to hire an intern who’s going to post the same stupid tweet every day that does nothing for my business?”

SP: Who better to advocate for you than you? Who else is going to have a better handle on your work, where it comes from, and how to express it most sincerely?

EH: That’s exactly right. You don’t have to do everything yourself, but you need to be directing it, because only you know why you created that thing. So if you turn that over, not only are you letting go of that as an opportunity, but you’re also augmenting the role of the middleman by asking him to interpret the value and purpose of your work. And that’s how we’ve gotten to a place where the cognoscenti decide what is good art and what is not. You’ve ceded that by not explaining it yourself.

SP: Buying art is a very personal thing, and many collectors value that direct connection to the artists.

EH: Yes, although it’s tricky, because artists want to do what they do. They don’t want to spend all of their time selling or managing the other stuff. Some people love doing that, and some people don’t, so I’m not suggesting that artists have to do it all themselves.

I think we might actually be emerging from a weird moment in which technology and the web made it possible for you to do everything yourself. I mean everybody can write a blog, everybody can make a webpage, and everybody can do all of these things. That doesn’t mean we SHOULD, because we’re not all good at everything. It is still entirely appropriate to figure out what you’re good at and what you want to do yourself, and then hire other people to do those bits and pieces you hate or don’t do well. All I’m saying is that you shouldn’t give up your right to manage the whole thing.

If you hire somebody to mow your lawn, it’s because you don’t like to do it, or you don’t have the time. It doesn’t mean you’re not going to inspect the lawn when the person you hire is done. You’re still going to use both sides of your brain to assess the work and decide if it was worth the cost. And if that person did a lousy job, you’re going to get somebody else to do it next time.

SP: So given all of these shifts, are you hopeful about the future?

According to a February 2017 Gallup survey, 43% of US employees now work remotely at least part of the time.

EH: Well, we’re moving in this direction regardless. The numbers of people who are starting their own businesses or undertaking all kinds of fascinating projects is growing exponentially every day. The old model–the worker bee toiling away in a large corporation–is fading. More and more people work on a 1099 basis. They’re being hired by more than one company. People change jobs, they change careers, and they change businesses. The entire workforce is doing this.

I think that’s a good thing for artists because it normalizes the ways they’ve always worked. Ozzie and Harriet thought it was outrageous to work from your home. It’s 9pm, and you’re still working? Or it’s 10 o’clock in the morning, and you’re playing tennis? On a weekday? As a culture, we’re now normalizing the idea that you can set your own schedule and that different people are going to do different things, sleep at different times, and work at different times. That is a very good thing for artists because then they’re no longer seen as odd. [laughs]

SP: Well, no more than the rest of us.

EH: I’m odd. I admit it. And when I look at my other consulting clients and the other groups and people that I work with, it’s the same. It’s just a heterodox way of thinking–that there might be more than one way to do something. That’s perfectly okay. In fact, it’s more efficient and productive.

SP: Even if you’re someone who clings to the old ways, you’re not going to have much of a choice. Things are changing, so you’d do well to adapt.

EH: Exactly, or you’re not going to have the same opportunities you did before, because now there are other ways for people to get things done. They don’t have to go through you. If you want to buy that car, you can Google the blue-book value yourself. You can do a little research at home first, and arm yourself for your meeting with the car dealer.

And that does two things for you. First, it gives you information with which to negotiate; you’re not going in cold, so you have the opportunity to get a better deal for yourself. And secondly, it gives you the confidence to negotiate.

SP: And that brings us full circle.

EH: Knowledge and experience beget confidence, and the combination of all three gives you the best possible chance at success.