In this Q&A with CHF Editorial Director Sofia Perez, Seth talks about the Booth’s much-anticipated exhibition, “Warhol and the West” (August 25 – December 31), and the museum’s efforts to serve as a hub for passionate collectors of Western art and the living artists who are broadening the genre.

When we think of Andy Warhol, we don’t often think about Western subjects.

Given that Andy Warhol is the most ubiquitous artist of the 20th century in America, you might think that we need another exhibition, publication, or book about him like we need a hole in the head, but here we are with an exhibition that is going to break new ground. It is based on new scholarship that hasn’t been published yet. There is going to be a 144-page companion book full of material about Andy that has really never been gathered in one place before, and it puts this part of his career in context so it’s really quite amazing.

Give us a few highlights of the exhibition that are surprising—not to you, since you’re a Warhol scholar, but to the rest of us.

Well, in the beginning, it was news to me, too, just like it’s going to be to the people who come to the exhibition or read the book. When Andy passed away in 1987, the Sotheby’s auction-house team that went to empty his estate and house found box after box of things he had collected. He was a hoarding collector—his entire house was full of stuff. He went shopping almost every day and bought something almost every day, and a lot of what he bought was American Indian artifacts, jewelry, pottery, baskets, rugs, and even some Western art pieces. He also had 300 Edward Curtis photographs.

It was an incredible treasure trove of stuff. When Sotheby’s sold the estate, the auction lasted for ten days, and one whole day was dedicated to nothing but Andy’s Indian collection. We’ve gathered together a number of the pieces that were sold at that auction, and they’ll be on view in the exhibition. So that’s one pretty wild thing.

Andy was an artist who said he had no political aspirations, and that social commentary was not what he was doing with his art. He said he was just a mirror held up to America to show them who and what they were. They were Campbell’s Soup. They were Brillo. They were Elvis and Marilyn Monroe. In 1976, the year of our bicentennial, when we’re patting ourselves on the back for 200 years of being a great country, which we are, Andy chose to ask some people, “Who’s the most radical Native-American person alive today?” The answer that came back to him from several people was, “It’s probably Russell Means,” who is one of the leaders of AIM, the American Indian movement. Warhol seeks him out through the Ace Gallery in California and winds up doing a series of drawings and paintings of Russell Means, who he calls the American Indian, and puts those works out in 1976. Is it a coincidence that Andy is drawing our attention to the plight of the Native American in the same year we’re celebrating 200 years of our history? I don’t think so.

That’s fascinating. When you start to think of the whole Americana angle, it makes him a very good fit for the Booth, but was that an easy sell to others, or did you have to convince people?

The Booth owned one of all 14 of the images that were in the Cowboys and Indians suite he did in 1985 and ’86, which was his last major project before he died. So we already had those pieces, but when I came here, they seemed like such an anomaly in the collection. The work was so different from most everything else he did—or that I thought he did—so I wondered why the founder of the museum deemed these important enough to include in the collection, which was generally composed of pretty traditional Western art. When I was going back to school to get my Master’s, I wound up doing my thesis on the Western portion of Andy’s oeuvre because it seemed like such an interesting area of study.

That was 15 years ago. Ever since, I’ve been working slowly and surely toward doing an exhibition someday, so it wasn’t a big sell here because of the history we had with it. The more difficult part, relatively speaking, was finding a couple of other venues that would be like-minded. Of all places, we got the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. Their art is generally pretty traditional, although they have stepped up a bit in the last few years with some interesting exhibitions, including one on Ted [Theodore] Waddell, who is a somewhat contemporary, almost abstract artist. I thought it was very enlightened on their part to want to sign on and partner on the Warhol exhibition.

The third partner is the Tacoma Art Museum, and this show is more up their alley, as they are a general art museum that has a great Western collection, rather than a Western history museum like the National Cowboy Museum.

It has made for an interesting partnership with three very different museums that have somewhat different outlooks. We’ve been able to cobble together what I think is a very good working relationship where all three museums have put in sweat equity—rather than one of the museums acting as the organizer and renting it out to the other two. We have each played to our strengths. The Booth pulled the checklist together, found the artwork, and kind of organized the show. The National Cowboy Museum handled all of the logistics—shipping, insurance, those kinds of things. And the Tacoma Art Museum handled the publication of the companion book, working with the University of California Press. The book will come out when the exhibition opens here at the Booth.

So the full exhibition is going to be shown at all three museums in sequence, right?

That’s correct. There’ll be a few minor additions and deletions, depending on some things that get added, elements of local interest, and there are a few items that can’t travel to every venue for one reason or another, but 98% of the show will be at all three locations.

How unusual is that level of partnership among museums of the Booth’s stature?

Generally, it’s more common to have one museum serve as the organizer, and then there are one to four other venues that pay some of the costs. Among Western museums, I think we partner a little more often, because we have an organization called the Museums West Consortium, which includes 14 of the most important and largest Western collecting institutions. We get together once or twice a year to talk about these kinds of things, so these sweat-equity partnerships kind of bubble up a bit more because we have that familiarity. You do see quite a few of these partnerships in our world, though I would still say that it’s not the majority. The majority are more along the lines of the “build it up and rent it to other people” model.

The Booth has always had a broader view of what constitutes Western art, but what’s been the conception of it in the larger art universe?

I think it’s going to be interesting to see the reception to this exhibition here, but even more so in Oklahoma, where we’re talking about a fairly traditional museum of Western history. For the last several weeks, I’ve been joking that I hope they have their lightning insurance paid up because it might strike when they start installing the exhibition next winter. There are probably some people spinning in their graves because Andy Warhol’s work is going to be shown at the National Cowboy Museum.

For an artist of his stature and fame, with as broad and far-reaching an oeuvre as his, to have done a series on Western art as the last major thing that he did before he passed—and all of the things that preceded it that were Western, that make up the context for this kind of capstone project within his Western works—I think you’d be very shortsighted to not see an opportunity to bring in a groundbreaking exhibition that’s going to attract a more diverse audience, a wider range of ages than you would get for any traditional Western art show.

A show like this seems important for the world of Western art—to be able to say that someone who was known for a totally different genre or style found this subject matter fascinating.

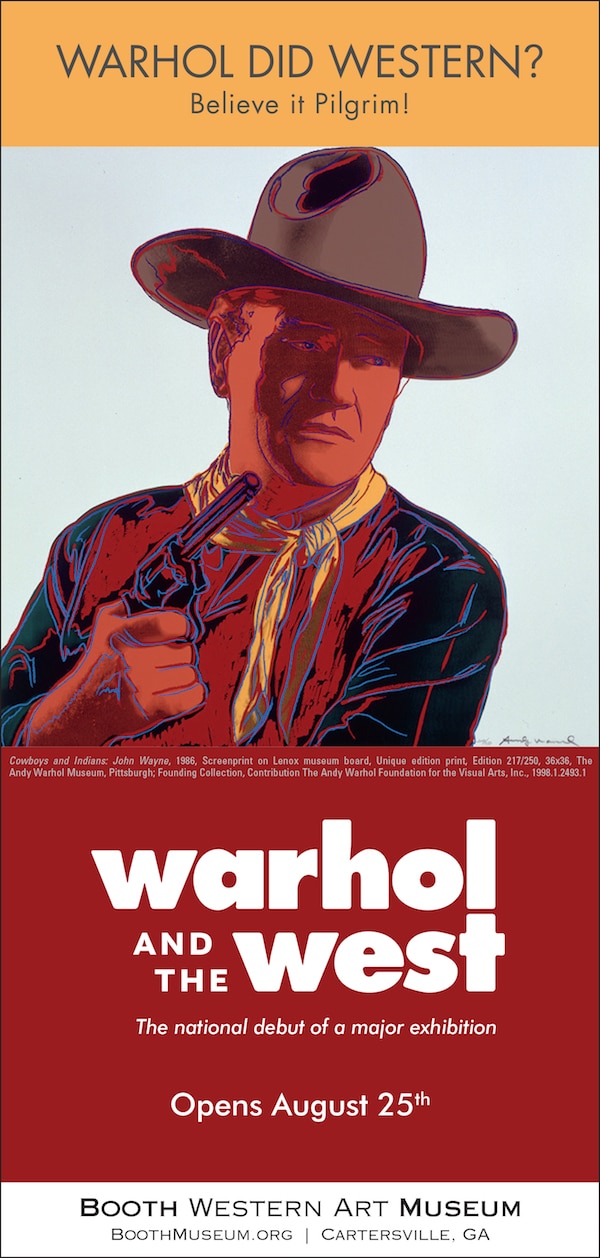

Right. Everybody I talk to says, “Huh, I didn’t know Warhol didn’t any Western art,” so the advertising campaign that we’ll be executing for the exhibition comes from that very line. It says, “Warhol did Western art?” and we will run that alongside his images of John Wayne and the words, “Believe it, pilgrim.” Or Annie Oakley, who says, “Sure shooting.” Custer says, “No fooling,” and Geronimo says, “Geronimo!!”

We really wanted to break out of the mold with our promotion. Normally, we do things that are very elegant and somewhat subdued. We really try to put Western art on an equal footing with American art and say, “Come see it for art’s sake, not just for the nostalgia of Westerns, or for the opportunity to be transported out West vicariously, or for whatever reasons you might want to come to the museum or to a particular exhibition.” But we’re trying to bust out of that with this one and say, “Let’s be funky and have some bright colors. Let’s have some fun, be irreverent, and really embrace portions of Warhol’s persona and his oeuvre.”

Of course there’s a side of him that we don’t necessarily want to embrace, the things that went on in the studio and in some of his films. But for the Western art world, I think it is important to know what he did and to take that a step further. One of the essays in the companion book is about his influence on the current generation of contemporary Western artists.

How would you assess that influence?

Well, I think there are a number of artists who have at least a little bit of a Warholian approach in their work. Probably chief among them would be Billy Schenck. Last year, I had the opportunity to go speak at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio when they mounted an exhibition of Warhol and Schenck side by side, with about 20 pieces from each. It was pretty interesting to see that comparison being made.

Artists like Tom Gilleon—who’s known for doing kind of a Tic-Tac-Toe board, nine images on a grid—certainly derived some of that from Warhol. And many other contemporary artists, be it Ed Mell, Kim Wiggins, Donna Howell Sickles, or Tom Ross, take at least some small piece of Warhol, in terms of his work allowing them to do what they do, to pave the way a little bit for them.

Then there are a number of Native-American artists who have worked in appropriation—Frank Buffalo Hide, for instance, and David Bradley—who have taken American commercial brands and transformed them into pieces that feature a pretty biting social commentary but that are based on iconic American ideas. David Bradley did a couple of pieces, one of which was called Land O Fakes, which is based on Land O’ Lakes butter. It shows fake Indian artifacts on the wrapper. He also did one that was a takeoff on the famous painting American Gothic, which featured a Native-American couple. He also had one with Lone Ranger and Tonto in those same positions. It really brings into question whose American dream is represented in American Gothic, who’s entitled to have that American dream, and where the Indians are in that story.

Those are all provocative questions for a museum of Western art to be asking. The Booth has also put on other shows that were outside the box of traditional Western art. Were those conscious attempts to expand the definition, allowing the genre to be seen as something more?

Yes. We think the tent for Western art can be much bigger than it’s been perceived to be in the past, and that any piece of art that comments on or depicts something that happened in the West could be Western art. Now, of course, you could get carried away with that, and pretty soon you’d look at some things and ask, “What’s Western about that?” If you don’t have a good answer to that question, I’m not sure that it belongs, but there are also some pretty innovative ways to answer that question.

We recently had a show featuring six Navajo master artists, two of whom are completely abstract. There may be allusions to real things in their works, but they are truly abstract paintings. They come from the spiritual and experiential nature of those artists, and they are an expression of their feelings and faith. When they’re Native American, and they’re commenting on or depicting things in their world and in their culture, how can you tell them that that’s not Western art just because it’s abstract?

You know, a lot of Jackson Pollock’s work has been compared to Western art. He was a true Westerner, and his drip method may have been based on Indian sand painting. Harry Jackson, the Western sculptor who was friends with Pollock, said that when you look at a Pollock painting, you’re seeing what it probably felt like to be in a stampede.

You basically built the Booth Museum in conjunction with the owners, growing it from the original idea in 2000, which was slated to be 30,000 square feet, to the opening of the first building in 2003 (80,000 square feet) and the expansion to its current 120,000 square feet in 2009. Now, it’s affiliated with the Smithsonian. How has Western art changed in those intervening years, and what role do you think the Booth played in that?

I think for us to claim much of anything in the way of credit for having changed the field would be a bit pretentious. We want to stay humble, but we do think that some of the things we’ve done, both in our collecting and our exhibitions, have helped to do what we were just talking about, which is to nudge the edges of the tent a bit further out and bring in some artists who might not have been considered core Western artists. At the same time, however, if you go back and read books and publications about Western art from the 1980s, they were predicting that the more contemporary side of Western art would be taking over and that some of those artists I’ve mentioned were going to be the new stars.

That’s happened to a small extent, but the traditional artists are still getting the bulk of the money and attention in the field. People are still predicting that the more contemporary side is going to take over at some point, but it hasn’t happened in the last 35 years. We try to keep our focus on collecting the best of the traditional Western artists that are out there, as well as the best practitioners from the more contemporary side. We’re trying to ride two avenues at the same time. On the contemporary side, I think we have established ourselves as a leader, if not THE leader, in collecting that material. The Eiteljorg is certainly doing a good job of that, too, as are others.

The Briscoe Museum recently came calling, and we loaned them 40 pieces from the contemporary half of our collection. At the same time, we also took some pieces out of our contemporary galleries to be part of a temporary exhibition called “Treasures From The Vault: 15 Years of Collecting at the Booth.” Even though we had to replace those roughly 45 pieces, it still looked like a decent showing in those galleries, so I am pretty proud of that.

When you’re expanding that tent, are you considering the fact that your collector base is getting older? Are you trying to ensure that the museum stays relevant to a changing art community?

That certainly is a concern among all of the Western museums, as well as the artists and galleries. We are losing collectors faster than they’re being replaced. The typical Western art collector is 65 to 70-plus years old. They grew up watching Western movies and TV shows, and came to collecting from that experience.

People who are 50 or 45 and younger didn’t grow up with that, so they don’t have those experiences. The dude-ranching industry, which was another way that people found their way to Western art, is also shrinking, and not popular with younger people today. That doesn’t mean they’re not going to love the West and the idea of the West, but they’re just going to be exposed to it somewhere else–maybe traveling to the national parks.

As those older collectors pass away, with kids who are not that interested in Western art, we’ll see a lot of it dumped into the market over the next ten to 15 years. I think prices can’t help but go down, particularly for material that’s mid-level and below. The truly blue-chip stuff will find a home and hold most of its value, but the next few years will potentially be a buyer’s market as big collections get broken up and the collector pool shrinks. Shrinking demand and increasing supply is not generally a good economic model, so living artists are going to have to work harder and smarter, and collaborate with us, with galleries and museums, to grow the pie instead of slicing it into smaller and smaller pieces.

So how are we going to turn younger people onto the Western art? How are they going to encounter it, and what is their response going to be? In theory, they’re going to be attracted to the more contemporary side, the imagery that is a little more cutting edge and modernistic. They’ve been saying that since the early 1980s and it hasn’t happened yet, although it seems clearer that it will happen going forward. As one of my colleagues says, “It’s nothing a great Western movie wouldn’t fix.”

The Booth also has a collection of Presidential letters and artifacts from the American Civil War, so it’s smart to position Western art as the story of America.

We are fighting an uphill battle. Western art is not the most popular thing in the South, and we know that, but when people get exposed to it, they tend to like it. They come here and say, “Wow, I didn’t realize it was going to be all of this,” referring to the magnitude of the facility and the collection, as well as the quality and variety of the work. I challenge anybody who’s an art lover to enter this building and not find something they can love. The Civil War and Presidential collections are smaller but still important and help provide context for the core Western collections.

We do get some snobby art folks who say, “Oh, Western art. That’s calendars or postcard stuff,” or whatever dismissive term they want to use. I defy them to come here and look at a great piece that has Impressionism or Cubism or Fauvism in it, and tell me that it’s not the equal of anything else that was going on in American art at the same time.

You do a lot of work with collectors of Western art, especially in the South, to empower them to keep buying that art and trusting their tastes to grow their collections.

Absolutely. We have become kind of the gathering place for people in the Southeast who love the West and Western art. They come here to our events, gala, symposiums, and exhibit openings, and get their fix without having to go all the way to Santa Fe or Jackson Hole. They still do that regularly as well, but in between, they can come here, and they really enjoy getting to know other people who have similar interests, because a lot of them think they’re the only crazy person in the South who likes this stuff—just as our founder probably thought when he was putting his collection together.

In many cases, we find people who live in the same subdivision, right around the corner from each other, and even know each other socially, but never knew that the other person collected the same things they did. We love putting together dinners or home tours with our members and going to see each other’s stuff. Pretty soon, these folks are meeting for dinner and going out West together, and they become emboldened, as you say.

We also provide them with the resources of the museum—our research library, access to curators, access to the artists when they come into town. On average, we have a major artist here every four to six weeks to do something, whether it’s teaching a workshop, giving a lecture, participating in exhibition opening, or just making an appearance. Getting to know the artists is a big part of it. We really place an emphasis on that.

It sounds like you’re helping these folks build their network.

Yes, and we’re not just doing that here in Atlanta. We’ve got little subgroups going in South Georgia, North Florida, and Tennessee (in Chattanooga and Nashville), and we’ve been working with a group in Dallas over the last two years. Since the death of Bill Burford, who owned the Texas Art Gallery, there’s not a museum or major gallery there that is offering the opportunity for people who are interested in this material to come together in a social setting and to provide programming for them. We kind of fell into it after three or four collectors said, “We love what you’re doing out in Atlanta. How can we do something like that in Dallas?”

We’ve been doing at least one quarterly event in Dallas, where we’ve now got 40 members that participate whenever we have a program with an artist, we bring an artist to someone’s home, or go to a gallery or a corporate office building to look at some Western art, and it’s been quite surprising. I was in Houston two weeks ago, and we may start doing the same thing there. People who collect this material really love it, but they don’t know many other people who do, and they want to have a social infrastructure and access to resources.

When you were asked to build the Booth, you were actually working as a television executive, having started as a journalist and writer, so you went back to graduate school to get your art degree. You applied your creativity in new ways. Do you ever feel a kinship with the artists that you highlight?

I certainly do feel a kinship with artists who started later in life since I started this career as my second tour of duty, so to speak. People like John Coleman, who was in commercial real-estate, a builder of buildings and seller of manufactured housing, for the first 20 years out of school, but was always thinking about art and came into sculpting when he was in his 40s. And Mark Yale Harris who’s a sculptor friend of mine. I don’t think he started until he was in his late 60s.

The bottom line is that the coolest people in this country make and collect Western art. They get tired of hearing me say this at the museum, but it’s true. In 19 years of doing this, I’ve met five jerks. And I challenge every person I meet by saying, “You tell me what business has that kind of numbers.” I haven’t had anybody come up with one yet. The other thing I always say is that Western art’s the only business I know where the customer buys dinner.

Given the climate we described—about a genre that does not always get its due—it takes a certain kind of individual to say, “You know what? I like it, and that’s what matters.”

That’s what makes them cool people. They’re generally entrepreneurial. They’re humble. If they’ve done great things, you have to pry it out of them. They don’t generally come out and tell you all about it. They’re not braggadocious people. They also have strong opinions, having usually built their own businesses by the sweat of their brow and their ingenuity. They don’t need art advisors to tell them what they like.

The artists are the same way. They’re also incredibly humble and surprised that they can make a living doing what they love to do and that people want to buy what they do. They’re very appreciative of the collectors. The artists, by definition, are also entrepreneurs, and the collectors get excited knowing that they’re putting food on the artist’s table, putting an artist’s kids or grandkids through college, and helping support them in what they do and the way of life that they have. It’s an incredible symbiotic and beneficial relationship, and I’m really proud to be part of it.

To hear more from Seth Hopkins, listen to his appearance on our Thriving ArtistTM podcast, when he talked to host Daniel DiGriz about how artists can collaborate with museums like the Booth.

Awesome article – and so in line with my experience.

Great article – and excellent interview