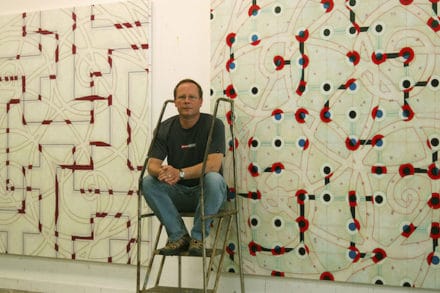

With more than 40 years of experience as an artist and educator, W.C. “Chip” Richardson has seen the art world from many different perspectives. Currently, he is the chairman of the art department at the University of Maryland, which in 2015 established a partnership with the famed Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. He is also a successful painter whose art is held in numerous public and corporate collections, including six commissioned works that are permanently installed at DC’s Reagan National Airport.

In this “Spotlight” interview with CHF Editorial Director Sofia Perez, Richardson discusses changes in the art industry, academia, and our culture at large, including the many ways that artists enrich our communities.

Did you always know that you wanted to teach art?

Actually, I always wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t know exactly what that meant. I grew up in an educated household, but in the Midwest—not New York. Los Angeles, or Chicago, where you might have more access to major art museums and a robust art community.

Actually, I always wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t know exactly what that meant. I grew up in an educated household, but in the Midwest—not New York. Los Angeles, or Chicago, where you might have more access to major art museums and a robust art community.

When I say that I didn’t know what it meant to be an artist, I mean that I was pragmatic, and assumed that I would need a day job. I had a great high school teacher, and I thought, “I’ll do that.” I wanted to go to an art school but my parents said, “We’ll pay for a university, and you can pay for art school.” I went to the University of North Carolina, in Chapel Hill, and entered their BFA program, but I planned to transfer to an art school after I finished my general education. Instead, I found the art program at UNC to be rigorous and challenging—there were a lot of terrific student artists there in the early 70’s—and I also found that I enjoyed academics, particularly philosophy and literature. I never transferred.

I tell my students this all the time: “You can’t know how this is going to end, but if you really want it, you work hard and do everything you can to get there.” When I was in school, my peers were far less aware of both the major and minor successes in the art world. I think our students today have a different view. The Internet passes information around much more fluidly and completely than in the old days, so they see success as more attainable.

For me, it was, “I’ve got to pay my dues.” In general, not a lot happened to you in the art world back then before you were 30. Now, I think there is enough economic incentive for galleries to mine the art schools. It’s more like pop-music culture, where you grab a bunch of talent, throw it against the wall, and hope that something sticks. That has pluses and minuses. It’s good that there are more opportunities for emerging artists, but it also gives you less time to incubate and grow your work to a level of maturity that allows you to handle the economic forces.

When you were getting your BFA and MFA, did those schools ever teach you the business side—how to make your career economically viable?

No, not explicitly. Back then, New York was one of the few places where being an artist was a respected profession—the center of commerce, the press, and many great schools, and that was the proving ground for art—but if you were in school out in the Midwest, or in North Carolina where I was, you were pretty far removed from the economics of art. My teachers told me, “The one place you can control is your studio. Get in there and work.” Whether or not it proved economically viable was not first and foremost on my mind then. Being able to afford paint, being able to afford a studio—those were my goals. Consequently, I thought about the possibility of teaching.

But I am a teacher by nature. When I was little, my first-grade teacher called my mom to say, “I can’t keep Chip in his seat. He finishes his work and then he goes around helping the other kids.” My mom’s response was, “Well, a) you’re not giving him enough work, and b) he loves to draw, so give him art supplies.” That was the beginning.

In graduate school, at Washington University in St. Louis, they had a very pragmatic approach, which was, “You’re probably going to need a day job or a support system. Teaching is arguably the best job that you can have to support your work.” When I graduated in 1977, it was a completely different job market in academia—almost all positions were tenure track. When I began teaching, I was 25 years old, on a one-year renewable full-time contract at Maryland. I found that I enjoyed teaching; it was stimulating, and it didn’t kill my artwork. With growing professional success, I was promoted to a tenure-track position and have stayed at Maryland since then.

There was a more coherent approach to the business of art in graduate school than undergraduate, as there should be; graduate school is the professional degree. Forty years later, we’re more coherent about mentorship. At Maryland, our BA program doesn’t require classes on the business of art, but we do offer them to those students who are the most likely to go on to art professionally. If you’re in a department within a university, rather than an art school, it requires a slightly different approach, which is why we emphasize interdisciplinary double majors. We emphasize the breadth of education, as well as a focus on art. Though there is a slice of our undergraduate population—the top 10%, say—that are similar to art-school students, in terms of their career choices.

To be clear, I’m speaking mostly about fine arts, because that was my background. In the old days, graphic design was criticized for training students rather than educating—it was viewed as job-related and task-oriented. “You’re going to be working for clients.” That was sniffed at by fine-arts people for a long time.

Now, at universities (and this is particularly true here at Maryland), we realize that there needs to be a discussion about career development and job placement. Students are more aware of this, and it’s a positive thing in the end. They shouldn’t be expected to pay this amount of money to go to school with no hope of earning an income. Although I will say that art students don’t have as much of a need for closure as other students; they’re better able to handle a DIY, gig-oriented economy.

They’re innovative in their thinking.

Yes, exactly. I think it’s become increasingly evident to the rest of the university that this department is a valuable point in the constellation of education we offer. We do open critiques. We knock around ideas in public. We don’t work in isolation and then put a product out there. We work in group situations. The term “design thinking” has become ubiquitous in business. We have this fluidity—and a lot of students do a double major that includes art.

Do your students ask about connecting with galleries and other practical business matters?

Our MFA program is the flagship of our department, and some of the students have exhibited widely before they come here. Studio space is very expensive, and if they can get a full ride for this program, they have a studio for three years, along with all sorts of incredible facilities. Universities are able to maintain currency and stay up with technological movements in digital media pretty well. So there are artists who use the university as an instrument. The technology and access to ideas that you find at the university are really important to their practices. That’s true at art schools, too, but we have a wider range of sciences and technologies to interact with.

Our graduate students come here with a sense of career trajectory. It’s really rare that we get someone who’s right out of an undergraduate program. Typically, they’ve been out in the world for a few years. They show work. They develop studios. We have a number of students who have come here after residencies, particularly in sculpture, because we’ve got a pipeline from major residencies, such as the Salem Art Works in New York and the Franconia Sculpture Park in Minnesota.

We have 12 graduate students and 12 full-time faculty, so our students work closely with us. There are many conversations, artist to artist, and that’s the mentorship piece of the puzzle. We also make sure that our graduate director is one of our younger faculty members, because his or her experiences are closer to those that our graduate students have had. I can’t give them as much advice about approaching academia, for example, because I got my job so long ago. We also offer travel support to our graduate students for conferences and things like that.

Right now, we’ve got a first-year graduate student from Iowa who just had a solo show at a gallery that emphasizes emerging artists in Washington, DC, and another who finished his undergraduate degree five years ago, and who’s had four solo shows and been included in 13 group exhibitions.

By its very nature, a university is an interdisciplinary community. Tell us a little about how that plays out for you and the art department.

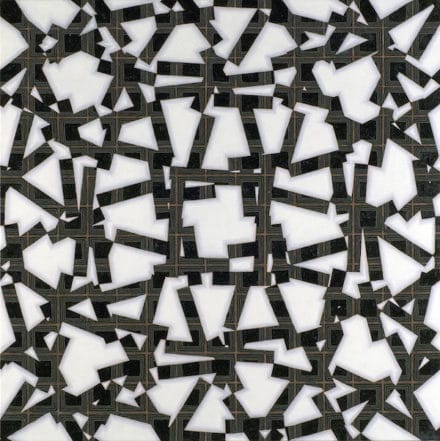

As an individual artist, I have a very narrow practice. I’ve painted on almost nothing but squares for 30 years. My artwork is not isolated, but it is narrow and singular, shall we say. But as a scholar and a thinker and a human being in the world, I’m an omnivore. I know about a lot of things, and I’m constantly making connections between them. Somehow, it is all distilled and compressed into my work. People have always seen scientific or mathematical references in my work, although it is adamantly abstract, and I’m not illustrating scientific principles.

As a university, interdisciplinarity is a value that is highly regarded and part of our strategic plan. There are support systems that encourage faculty to work with other faculty. We have a digital artist who works in projection and installation, as well as with physicists, and a sculptor who works with electronics and sensors, and collaborates with geology professors. The graphic designers here help with data visualization in multiple areas. The folks at the computer-interaction lab have had a relationship with two of our graphic designers for a good six-year period because the former didn’t know how to make their data visible, and our designers were able to help them do that.

So there’s this constant looping and connecting, and we find it to be true among our students, as well. At an art school, everybody’s focused on art and what it can be, but I’ve sat on the panel here that reviews the top students—the ones who are going to get the full-ride scholarships. They’re primarily in the STEM disciplines, but it’s incredible how talented these kids are. They come in with music, dance, visual arts. These students find us for electives, and some of them get hypnotized and become art majors.

That interdisciplinarity has increasingly become a value that is respected and desired by the university, by the College of Arts and Humanities, and by all of us internally. We start with the disciplines of the hand and traditions, but we blend seamlessly into the use of new technologies. You could argue that oil paint was a new technology at one point, because painters wanted to move away from frescoes and be able to transport religious paintings to churches in the hinterlands. Our department has been a first adapter of many things. I think we got a 3D printer before, or simultaneously with, the engineering department.

There are many interconnections there. We’ve had students help with murals in the community—sometimes as volunteers, and sometimes on a paid basis. We reach out to the community more than we ever have before, and art is a great vehicle for the university.

Is that thinking what led to the partnership with the Phillips Collection in DC?

The art gallery here is small, and Wallace Loh, the university’s president, recognized that we were the only major school in the big 10 that did not have an art museum. Originally, he formed a task force to consider a partnership with the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Corcoran School of Art. That partnership did not pan out, but the same task force (which I was on) did support pursuing a partnership with the Phillips Collection. It’s a wonderful smaller museum that doesn’t have a school attached to it, but it’s got an educational component and some really great people. Plus, it gives us a footprint in DC.

In the three years since the partnership began, the two institutions have worked on a number of joint programs. The art department is specifically partnered with the “Conversations with Artists” program, which presents events at the University of Maryland Center for Art and Knowledge at the Phillips Collection. We join the Phillips’ curatorial staff to set the loose thematic structure for the year’s program, make suggestions, and select artists.

They bring in three visiting artists per semester, which has provided us with six artists per year. Our students go down to the museum to hear each presentation, and then the artist comes out here the next day to do critiques with our MFA students and have lunch. The curators have been wonderful and engaging. Last spring, they reached out to us and said, “Hey, we’d love to come out and see your graduate students’ work.” They joined us for studio visits and a potluck cookout at semester’s end. From our perspective, this part of the partnership has been wonderful, and a great boost for our program.

So much has changed over the past 40 years, and there are now many paths to success beyond gallery representation. How you do you counsel your students about navigating all of it?

When it comes to getting your work out there, it’s so much more varied now. I tell them to be selective. Don’t kiss the first person who compliments your hat.

Not all venues are equal. If your goal is to make it to the big leagues, there are certain paths that have proven more successful than others. We try to guide them gently towards those paths, but we also recognize that there’s going to be that kid in the back of the class who figures things out in unexpected ways. The world has changed. There is an entrepreneurial spirit out there that is enabled by the Internet, and by communication and social media. The students make huge use of it all.

In 2000, I moved from an older, more established gallery in DC with very little web presence, to Fusebox, a new gallery in town. The owner was younger, and she was very smart about the Internet and social media. This was a natural shift at that time because social media was just blowing up. I was fascinated by the new approach to marketing art and artists. It was also interesting because I had been one of the youngest artists at my previous gallery and was now one of the oldest. I have definitely had different positions in the mentoring chain.

Along those lines, how has the reality of being an artist in this culture changed relative to what you thought it would be when you started?

My approach hasn’t really changed much over the years: I’m communicating to the world my interior, whatever that might be. I am making something that I hope other people will look at and respond to—that it will engage them in a kind of quest for consciousness, for lack of a better term.

However, I do think that being an artist in contemporary society has changed. With the communication and dissemination power of the Internet, art now has a decidedly more international feel, and that is good. I also think that socially and politically engaged art is stronger now than ever. The same is true of identity-focused work. And audiences are more engaged with this content as well.

I know that the best audience for my work, the audience I care most about, is other painters—not just other artists, but specifically other painters—but I also love it when a plumber who has come my house sees a painting on the wall and starts asking me about it. There’s the personal exchange that occurs, what the great philosopher Kant referred to as a triangle. He was talking about poetry, but you can translate it to paintings. It’s a triangle that’s composed of the maker, the thing itself, and the viewer.

Marcel Duchamp said, “I send it, you catch it.” Our work is completed by the viewer. Whenever I visit New York, I spend 15 minutes looking at a Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie in the MoMA, to charge my batteries. Mondrian wasn’t speaking directly to me, but there is this connection that is what he sent and what I caught, and in combination, that’s the work.

What about the role that artists play in transforming communities?

Artists have always been the shock troops of renovation. I’ve seen that in every city I’ve lived in—St. Louis, Cincinnati, Chapel Hill, Baltimore, here. You saw it in New York’s SoHo in 1970. It was all artists. TriBeCa, too. There’s a lot to bemoan there, because eventually the artists who really get it off the ground get squeezed out economically.

I have lived in this area since 1978. I’m in University Park, which is on the Route 1 corridor here, and I love it. It was named an arts district 20 years ago. That designation had no impact for a while. They set up housing and work-live studio spaces, but there was a structural problem: If your income was low enough for you to qualify for these places, then your economic stability was weak. There ought to be multiple tiers so that more established artists who don’t fit the low-income profile can move in and bring what they bring to these communities.

These were neighborhoods that were undervalued inside the Beltway, near Washington, and a lot of artists moved in because we couldn’t afford anything else, so there’s a density of artists. There are murals everywhere, and there’s this real sense of community. There’s something going on. Pyramid Atlantic, which is a great print studio, is open to the public. There are many community-facing arts organizations and galleries. There’s activity and energy, and that becomes an attractor for people because their lifestyle is enriched by the arts. Everybody understands that. It’s valuable and viable.

Under the presidency of Wallace Loh, the university has figured this out as well. They recognize that they’re a major partner with these communities. The University of Pennsylvania is another great example. They were a community with a moat around it inside a pretty sketchy part of Philadelphia, and there was a real disconnect. But instead of building higher walls, or having more electronic surveillance, they bought properties and developed the community. They set up grant structures. Maryland has done that as well. There is a premium value placed on community-facing projects. These partnerships only make things better and stronger for everybody. The sense of community on campus has increased exactly as the sense of community off-campus has increased.

Our arts corridor had David Driskell behind it. (He’s one of the leading African-American artists and scholars in the country. When the White House bought its first African-American work, they consulted with him.) He was on the board initially, and made pragmatic and sensible aesthetic recommendations relating to community development. “Get rid of these used-car lots. All those silly flags and things.” That sounds trivial, but it means having somebody who is visually aware of architectural integrity and planning. And the architecture and city-planning component of the architecture school here has also been very engaged. The Ivory Tower is less of a tower than it used to be, and I think that’s good.

It sounds like there’s more respect for the role of the artist, and a drive to integrate them into planning processes. It’s the innovative thinking you mentioned before, that comfort with open-endedness.

Absolutely. I think you hit the nail on the head. If you go back 40 years, performance and installation were still radical. Now, installation is the most common expression in our graduate program. These days, the variety of art impulses is so much greater than it used to be, even if you just look at painting, which is pretty stodgy. Painting technology hasn’t changed in 35,000 years—it’s colored mud and a hairy stick—but it has broadened greatly compared to when I was in school.

A lot of it has to do with technology, and a lot of it has to do with context. Where do the paintings go? People now expect that art is going to be integrated with architecture more than it was before. It’s the 1% rule [Ed. note: first implemented in Stockholm and later adopted elsewhere, stipulating that one percent of the total cost of built projects will be allocated to publicly accessible artwork].

That translated into putting businesses and artists together. Once they began communicating with artists, they realized that value goes far beyond producing a bubble to hang on the wall. There’s creative thinking there, and sensitivity and awareness of our visual world. You hear of artists working as consultants in a variety of situations—but as artists.

Dario Robleto was a visiting artist at the Phillips, and he has made his living as an artist over his entire career. He’s figured out different kinds of support, and he’s been very successful. At one of the museum’s events, he talked about being part of a scientific team—I think it was in oceanography—and about how the team brought him on as an artist. “They’re not interested in me doing their science.” he said. “They want to bounce their ideas off a different kind of wall.” I think that speaks to his ability to communicate—he’s a brilliant guy—but it also speaks to the openness of the scientific team. One of our faculty members just came back from seven days in the Arctic Circle, and another is going in mid-summer; both are working as artists in a scientific context.

If scientists are studying volcanoes or rock formations in Iceland, say, they may be looking at the issue through one lens, but having a different lens might help them see things differently. We in the arts are wide open to that, because we’ve been using the sciences and other fields to flips our lenses for a long time. That’s what artists do. We pull in all these different signals from the world and compress them. Art is a compression of life. When the right consciousness unfolds and unpacks it, that’s the art experience right there.

Sofhia Perez, thank-you for another insight filled article; a great look at the contemporary visual art field.

W.C. “Chip” Richardson I enjoyed your stories and experiences- especially how the artist is your best intended audience! I am just finishing a great book that you may like too “Exploring the Invisible” by Lynn Gamwell. She draws the parallels between science and technology with the development of the visual arts. It may give your students a great new way of understanding art history. Thank you.