Business is hard. No matter what the business is, it’s the business of our life, and it requires focus, determination, and simultaneous attention to tiny detail and big vision. The only way to escape taking care of business is by falling down on the job—by doing whatever lies in front of us halfway or badly. And that’s not an option, right? We’re all on this planet for specific reasons, and while we might do well to quit jobs that are not helping us accomplish whatever our personal business is, we’ll always wake up the day after leaving those ineffective jobs with the same real one: identify what we’re supposed to be doing and DO IT.

This is not simple or easy for most of us. The hermit meditating in the mountain cave first had to learn how to meditate, then climb all the way up there, and finally has to implement his intention. Before all of that he had to realize that his purpose was to set himself apart from everyone else, and dedicate himself to that solitary path. That’s his business and it’s formidable. I certainly couldn’t sustain it. But then his purpose is not mine.

No Net

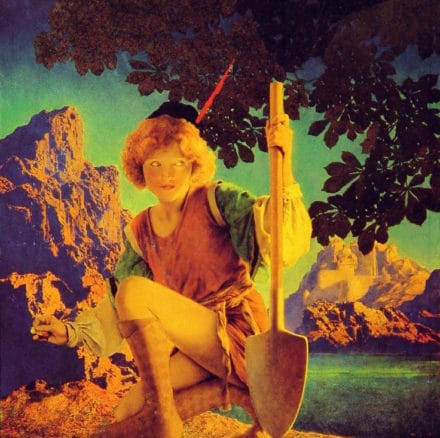

It’s possible that the hermit always knew his calling, and that he just had to move in an orderly fashion down his path, removing obstacles, and working diligently in a straight line up that mountain and into the cave. This was the case with my father, who used to say that he was successful because he was only really good at one thing, so he couldn’t do anything else. He was fantastically fortunate to have done a pastel portrait of his stepmother when he was in first grade. He got a likeness and everyone knew it was her. So from the age of six everyone knew what Clark’s job was. But his father worried about him. He didn’t want him to be a “starving artist.” So he forced him into a completely different career. Eventually my father made his way as a painter anyway, but he had to fight his whole life to be allowed to do the one thing he knew he was good at and meant to do. The end result is masterful, but it wasn’t easy.

Jack of All Trades

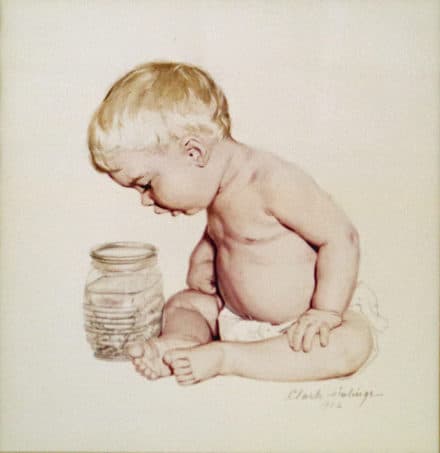

On the other hand, if you only have one option, you have no decisions to make, and you can’t second-guess yourself. Just watch that baby who’s struggling to stand. She’s red-faced and yelling in frustration, but she keeps getting back onto her feet and working to stay on them. Once she masters that, her business will be to sort out how to move those little feet forward one at a time without falling over. That’s the job of a baby, and she can’t not do it. Sometimes it’s easier to have only one option, even though it might not seem like that at the time.

My father always said he felt sorry for people who naturally excelled at many things, because when the going got tough, they could just quit and move on to the next thing. While life may seem easier for multi-talented people, it’s not necessarily rewarding. Not having the option of doing B+ work in a different field forces one to do A+ work in the one area in which they excel. If that lump of coal could roll out of the mine it would, but then it would never become a diamond.

The Scenic Route

Many of us do flit from one thing to another, but in most cases all that flitting around, trying out different things and learning bits and pieces, eventually adds up to something useful. All of those experiments and segments of information and knowledge do get put to use. I have a friend who is brilliant, good-looking, personable, and good at everything. (Exactly the person my father felt sorry for, haha!). This friend started out in marketing, which he ended up hating. So he went to drama school for dramaturgy. He did some acting and playwriting, too. Then he worked at Actor’s Equity, where he had a front-row seat for organizing, advocacy, and the herding of cats. He also got up at 4:00 AM every day for a while to apprentice with a master bread baker. The early mornings worked for him, but all the alone time didn’t.

Eventually, my friend found his way to yoga and dove into that head first. Now he runs his own yoga practice, leading large classes according to curriculum he devises, managing the administrative aspects, handling the marketing, etc. It’s a little performance, a little writing, some cat-herding…in fact, all of his previous experience is brought to bear on this yoga career, and he is thrilled to be doing what he is meant to do.

It used to be that people would wait until they retired to sort out their business. Sometimes that meant never doing it. First they would work for “the man,” and then they would not work at all. That has changed, though. Today’s average American has seven careers, and very few ever retire. Some of this is because of financial constraints, but most of it is because we are no longer willing to complete our lives without accomplishing our own business. So we search for work that meets our own goals and needs, and it’s not obvious what that work is. For some, the work is in figuring out the work.

That Thing with Feathers

I have spent many years making it my business to help others figure out how to accomplish theirs. I am lucky in that I am not good for much else. That said, my path has not been straight-forward or clear. It took a long time for me to figure out the right venue in which to do this work. I still have a lot of my own details and vision to think about, and I struggle just as much as everyone else does with both of them. I become exhausted by paperwork, lose sight of my goals, and collapse into bed completely demoralized. Then I wake up the next day with a little more energy and concentrative abilities, and with renewed hope that the vision is once again clear. Often I don’t and it isn’t. So I do what I can, just like that baby girl, because I have no alternative. The desire to accomplish something always outweighs the desire to avoid struggle, drudgery, and frustration.

One thing I have discovered that helps me keep going is that I must periodically take stock. I must stop wherever I am, turn around and look back at where I’ve been, and acknowledge that I have made progress. If I stare only and always at the impossibly long, hard, obstacle-ridden path in front of me, I will fall into despair, lose momentum, and flail around needlessly. Unless I force myself to see what I have accomplished, my imagination will run amok, and that is not helpful. (If my dentist tells me I need a root canal, my instinct is to schedule that procedure as quickly as possible, the minute I get out of the chair and back to the reception area. That’s because I know thoughts of dread will preoccupy me until it’s over. I will imagine the worst-case scenario—almost always a horror that does not come to pass. So the less time I have to imagine, the better.)

I have been thinking about that this month as I’ve been reviewing the CHF Fellows’ proposals and they have been working on field reports. I have been seeing the tremendous progress they’ve been making; they have been juxtaposing what they declared they would do against what they’ve actually been able to do, which for many of them has not been one and the same.

Always Declare Victory

One of our Fellows did do what she set out to do, but the results were not what she had anticipated, so she felt her report was about failure. Of course that’s not true. Life is nothing but one experiment after another. With each experiment we learn something—if we take the time to take stock. That means tracking things, reviewing what we’ve done, and launching a new experiment accordingly. If we don’t track what we do, we’ll have no perspective, and (in my case) we’ll imagine the worst, instead of acknowledging all the hard work and celebrating what has been accomplished. The only real failure is the failure to try. Our business is to try.

That said, field reports are the definition of drudgery, even when everything has gone swimmingly. Unless you’re a particular kind of personality, they are not something to look forward to, and they often make us want to yell and scream. But once we’ve done them, they help us see that we are succeeding, no matter the outcome. Without them, we are bound to lose sight of our progress. We usually create reports for others, but I believe the most important audience for my progress report is me. Just as reality never measures up to our plans, so it is never as awful as we imagine it to be if we fail to document the truth. By celebrating the accomplishment of having done the work, we maintain the energy to keep trying, and the momentum we have already built.

Only Zeus had things spring fully-formed from his head (and his relationship to them was fraught). The rest of us have to put in the work, and we have to accept that what we imagine in our heads will never be reality. We may be yelling and frustrated sometimes, but we’ll be even more so if we stop. Stopping is not an option.