How do we create a robust society? How do we produce a dynamic, powerful culture at a time when we are fracturing, polarized, and creative enterprise is an afterthought?

Taking Stock

Let’s remind ourselves of where we are. If you look around, you see political fragility, economic uncertainty, a rollback on civil rights, and general unhappiness. That’s depressing. That’s the point. As a people, we ARE depressed. You don’t look back at 2021, let alone what’s going on now, and say, “it’s a happy time.” We’re not happy and we have to face it. We’ve essentially got a global war, and a recession only partly driven by that war. We’ve got a big economic bubble. We have a politically fractured culture at a global level. Totalitarianism, never the friend of a creative culture, is coming back in vogue. We’re at each other’s throats. We’re not happy.

The beast is slouching toward Bethlehem. The earth is heating up. We’re settling into (if we’re lucky) a mere detente as two nations living in one national entity. Arguably, we began going in that direction in 1945 when we settled into the Cold War—which generated the Korean War, the Vietnam War, El Salvador…We decided to live in a state of permanent animosity, driven by munitions manufacturers, the intelligence apparatus, and the munitions and chemical industries that profit from it. There was a huge amount of money to be made. Those chemical makers clean your baby, make for a sparkling kitchen, but they also deforest Laos.

All of that to say that we’re now in an understandable state of fragility when it comes to the role of creativity in our lives. We have a tenuous relationship with art.

We do not even dream so much anymore. Our dreams are smaller. We don’t dream of a world that flourishes, and we haven’t been given a mechanism to build better dreams. The material on CHF’s website is an insistence that there is another path, and that we’re working to solve that problem in a robust way.

How do we get a flourishing culture in the first place? That question is the entry point to the conversation we are creating. As a culture, we tend to put creatives in a box. And even the goal of showcasing artists as essential workers and ensuring they’re well-paid is not yet dreaming big enough. I think even those dreams are too small. I don’t want to be a useful cog in someone’s wheel. I don’t want to work for somebody because I have the skills. I want to work for somebody because without creative enterprise, we’re not “making it” as a culture.

What Now?

We must move away from the merely theoretical lament, and toward doing something practical and economically powerful. Without that, we don’t build a robust creative culture. We must build a road for artists to thrive, and creativity to flourish, and it has to be done at the economic and investment level.

Anything less creates the same problem we had all through the Cold War, which is the starving artist syndrome. Only 1% of artists can be famous, and only those who know the right people and happen to gain the approval of the tastemakers can make any money. Everybody else is dirt poor and living on their cousins’ sofas.

There are very real challenges involved in making a creative career in this outdated system that takes power out of the hands of individual artists and favors a tiny percentage of creative workers. In a recent report, Art Basel notes that despite hopes that the COVID-era digital revolution would be more equitable, they found that “the digital shift had done little to reduce the market’s hierarchies, and the high end began once again to pull away from the rest of the market, with an even denser concentration on fewer artists and businesses in most sectors.” So, interestingly, not even the advantages of the pandemic era shift are coming to level the playing field—at least not at the high net worth level.

The Bottom Line

This culture of scarcity in the arts is so frustrating when there is so much hard data to support the measurable economic contributions of art and artists. They are a force to be reckoned with. In 2020, arts and culture added $876.7 billion, or 4.2 percent, to national GDP in the United States—and was a larger contributor than transportation, mining, agriculture, or forestry (Source: NEA). In 2020, the US had a $28 billion trade surplus in arts and cultural commodities. (Source: National Assembly of State Arts Agencies). This NASAA report also contains a telling finding: in rural communities, one performing arts center doubles the chance that local businesses will be design-integrated and innovative—and businesses with those qualities are shown to be recession-resistant AND see faster growth in weekly earnings. Business needs art at its very core.

CHF Steps Up

What we’re doing at CHF isn’t sexy in a theoretical way, but it’s actionable and practical. We’re asking people to dig deep into the thought process of how we get a culture that we want to live in. And we are starting from the premise that you don’t get a robust creative culture without a thriving creative economy.

I don’t think we’ve widely connected the dots between these big questions—first, daring to ask them, and then to dream of the ubiquitous, middle-class artist. How do you actually do it? What is the day-to-day? How do you actually implement it? And that’s where we actually do have an answer.

It starts at the level of mindset and knowledge. We foster a conversation around art as a business, and we empower art-entrepreneurs with the kind of business training all other industries require to flourish—tailored to the unique demands of the professional creative process. We connect creative professionals through peer networks. We encourage and nurture pivotal projects that accelerate artists’ careers, regardless of their aesthetic style. We train artists and makers in self-sustaining entrepreneurial practices. And we galvanize—not just artists, but ourselves—into a movement with a pivotal aim which, at the risk of being repetitive, is a culture teeming with creative ingenuity and newly reliant on creative intelligence. All of CHF’s programs, of which there are many, are devoted to these ends.

More Is Less…

Can we really say this is not important? Are we willing to call it a pipe dream? If we settle for that, we get more of what we’ve already got—more of what we’ve gotten over the past 70-plus years. And really, that kind of more is less. Much less.

But What If More Is More?

In the midst of this, cranky old white guys like me think most contemporary music sucks and art is mostly garbage. Some of us have tastes that don’t go beyond 1984. Even if you don’t agree and you dig music from 2022, how do we get more—of what any of us want—in our culture? We get more by encouraging more of everything. By generating a robust dialogue, a conversation among artists who are actively thriving, economically empowered, and independent of a small cadre of tastemakers. Regardless of what taste that is.

The most common answer I’ve heard is to sit and wait for government funding. “The government needs to do more to save us. They need to bail us out. They need to have more programs.” Of course, any elected official could stand up there and say, “We’ve got to create a thriving, creative economy.” But that just gets one person elected. Then we go back to business as usual. There’s no systemic change.

Our fundamental divisions make the political sphere the least likely source of answers. We don’t actually need to wait on a better Congress, a more interested President, a different Governor, or a more just Supreme Court. And we can’t afford to only advocate for that. We need to be in action at the grassroots level.

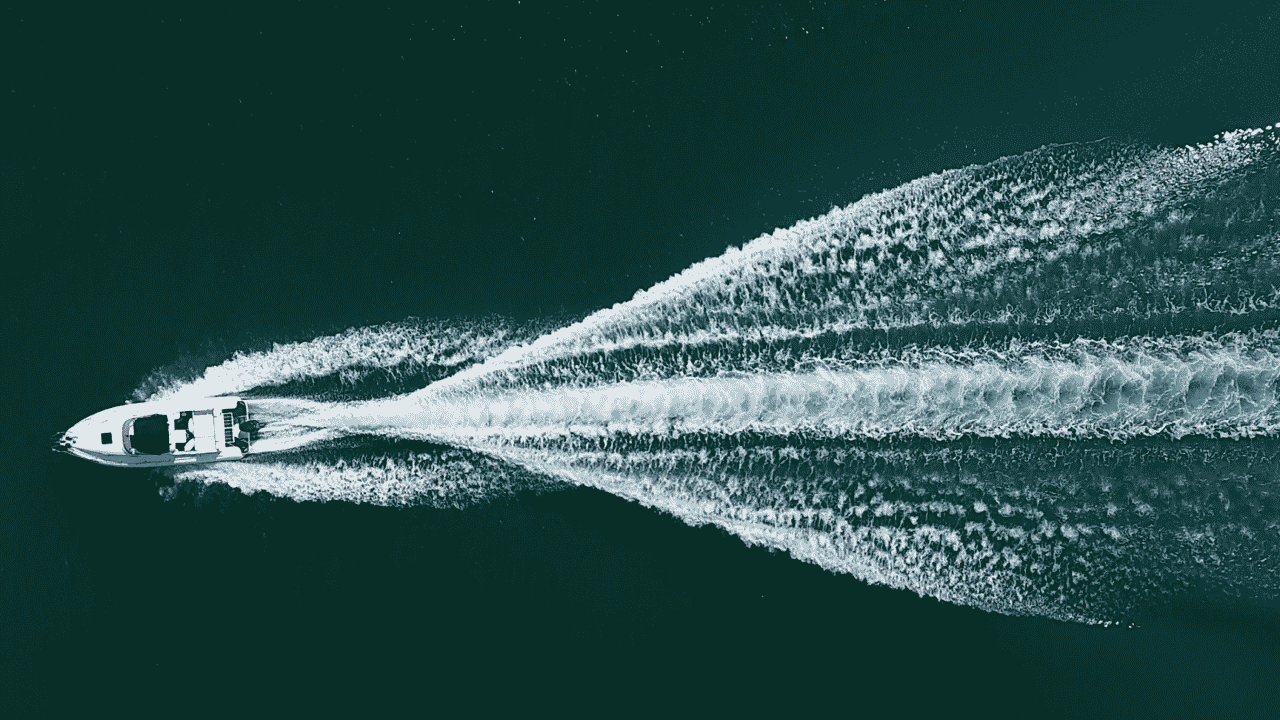

No one’s coming for us. We’re on an island and the search has been called off. There are no planes or boats coming now, so what do we do? Either we build our own boat—ideally, a speedboat, and not just an ark for preserving the bare minimum for the survival of the species—or we’re stuck here.

That’s where we are. And we can build it. We have the architecture for building that boat. So let’s do that.