“…Beauty does not reserve itself for special elite moments or instances … The grace of hidden beauty becomes our joy and our sanctuary.”

—John O’Donohue, Beauty: The Invisible Embrace

I’ve been thinking again about a column penned just a few months ago by New York Times op-ed columnist David Brooks. In it, he decried the diminished value of beauty in today’s world, and placed the blame largely on artists for abandoning aesthetics in favor of punditry. While I’m grateful that Brooks has called attention to a huge issue, he’s wrong about its nature and source.

Unless they are born into wealth and can otherwise feed themselves, artists must battle to earn a living in a system that is rigged against them. Power rests in the hands of risk-averse gatekeepers who decide what kind of art is worth selling and buying, to the exclusion of everything else. When artists deviate from the orthodoxy of the moment, they are told there is no market for their work, while those who follow the dictates of the cognoscenti face stiff competition from the large numbers of peers who are producing similar kinds of work.

An Uphill Battle

It is already a tough climb for most artists to support themselves through the creation of art that matters to them, and that slope is getting steeper by the day. For starters, there’s the ever-increasing cost of doing business. Visual artists need clean, well-lighted workplaces, too, and many have specific studio needs, including rooms ample enough to accommodate large-scale pieces. As The New York Times reported last August, the cost of these spaces is increasingly out of reach.

Next, there are the other upfront expenses that artists must cover—including materials and the cost of transporting finished works. It’s challenging enough for brick-and-mortar businesses to qualify for financing in the current lending environment; imagine the reaction a sculptor receives when she asks for a loan so that she can erect a 10-foot-high bronze which may or may not find a buyer.

When artists struggle to earn their living on the open market, they are forced to turn to arts funding instead, a source of support that continues to dry up. In 2014, individual artists received less than 5% of the grant dollars awarded by nonprofits or state arts agencies for arts-related work, and most of that support was filtered through fiscal sponsors, creating an additional obstacle and cutting into the total award.

But the biggest challenge artists face—and one that, if met, could help them overcome the others—is the one that gets the least amount of attention: a dearth of business training. Art schools rarely teach strong organizational skills or proffer business knowledge, nor are art students instructed on how to manage risk and reward, but all of these capabilities and resources are crucial if an artist hopes to have a long and successful career.

Scaling the Heights

Beyond honing their techniques and creative vision, artists must also learn how to create budgets, inventory and track their pieces, price their works appropriately, network with key figures in their industry, and promote their work on a shoestring budget—all while navigating a highly predatory environment where most of the “support” they receive comes from middlemen who seek to profit from their lack of business experience.

It has never been more essential to equip artists with the tools and training they need to take the reins of their businesses. The massive changes being wrought by technology—e.g., the rise of online art sales, and the resulting decentralization of the market; the creation of cloud-based promotion tools; the increasingly unmediated relationship between artists and the public, etc.—provide artists with a tremendous opportunity to break out of the boxes constructed around them, and find their customers.

If the notion of the artist as CEO is jarring, think again. We cannot persist in subscribing to the ridiculous belief that they are unable to manage their own affairs. They are exactly as capable as the rest of us. Furthermore, artists are engines of economic growth in our communities, establishing studios in affordable but downtrodden areas, and their presence becomes a magnet for development. When they are later priced out by gentrification and rising rents, they pick themselves up, and go through the entire cycle again, much to our collective benefit, if not to their own.

Contrary to the argument Brooks makes, we do in fact need more artists, but numbers alone won’t do the trick. Our artists must hail from all quarters, and they must be free to work in whatever styles or movements they wish (and even create entirely new ones). In order for that to happen, however, they must learn how to succeed at the business of art. Only then can they have the kind of longevity that allows them to develop and mature as artists. Picasso did not become Picasso on the strength of his first painting.

Beauty Is Everywhere You Choose to Look

But there is one more vital piece of the puzzle: the art-consuming public. While each artwork is the product of an idiosyncratic vision, the market for art is no different than any other market—it is driven by supply and demand. If our culture takes art for granted, the only artists left will be those who can afford to pursue their visions all the way to the poorhouse.

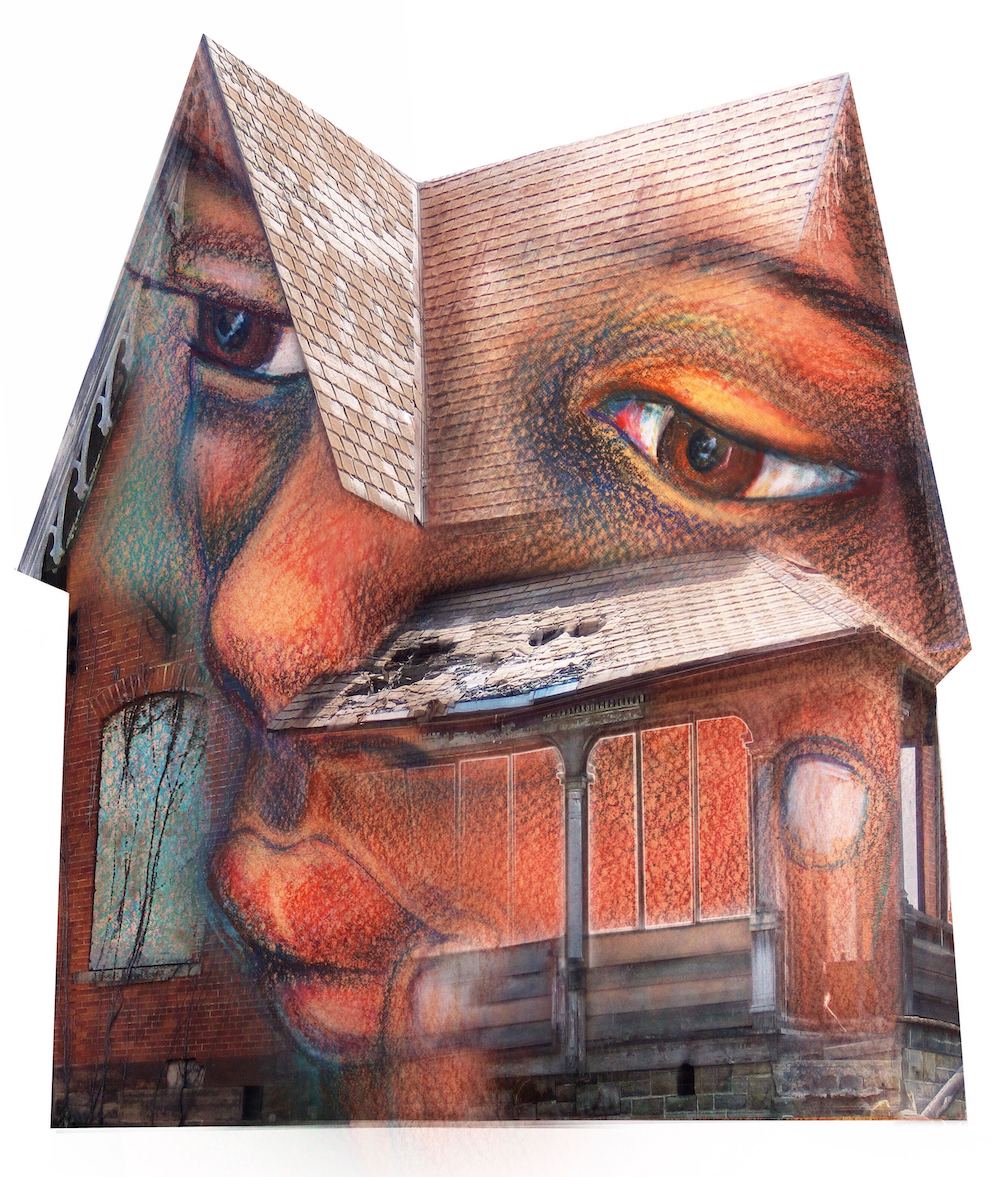

If, as Brooks complains, we no longer bump into the kind of art we enjoy as we walk down the street, we must go in search of it. While the visual artists who create it may not be as immediately visible as folks like Jeff Koons, they are out there just the same. They need clients who appreciate art in all of its transformative power, and who are willing to back its creation. And art aficionados need to trust their own judgment, and invest in the type of art that moves them.

Not everyone can afford to take part in a Sotheby’s auction, but we can all avail ourselves of the many tools at our disposal to find and support artists whose work we enjoy, and who enrich our lives in ways large and small.

To receive Elizabeth Hulings’ “Director’s View” column by email each month, please sign up here.

Well Said!

Thank you, Elizabeth, I remember the Brooks editorial you’re referring to. I think you’re response is informed and spot-on. Thank you and keep up the good work you’re doing.