Your writing sucks. Your sales pitch is bland. And your speech, presentation, or workshop is underwhelming.

Got your attention? My work in all of these categories has suffered the same fate at times. Quite often, it’s simply because I started in the wrong place. The art of performance is passion in life, but I’ve flubbed it more times than I can count, and I KNOW when it doesn’t work. What has been helpful to me is having TOOLS to understand why, and to know what I can do about it.

Take writing as the entry point. Amateur writers write from the beginning. Authors write from the middle. I say this because I’ve spent most of my life as an amateur writer looking at authors who, on the surface, seem to have a grasp of unattainable mysteries. They do not. Writing powerfully, like Stephen King and Dean Koonz do, is a craft, and it can be learned.

If I’m writing about the world under an antichrist’s reign, my inclination as an amateur is to start from the beginning—the “before” time—and write forward, showing the rise. An author writes from the middle, fast-forwarding to the point where the antichrist already has full sway, and writing from there. He might hold back a smidgen of that sway so that there is somewhere to go with the story—because both good and evil take time to develop.

“It was an ordinary day in an ordinary year on an ordinary street, and I went to the corner for a cigarette, as men of my generation and social class were wont to do on brutally hot afternoons in New York in August. Bill was there, and Tommy, and the two Ernesto brothers, whose wives and girlfriends drove them varying degrees of crazy, until they fled for the pool halls or the corner of 198th and Valentine…”

“I got Tommy’s call at 4pm on a Tuesday. “Get your gear. It’s time.” We met up with Bill and the Ernesto brothers at our usual corner–198th and Valentine. Tommy showed up late. “Got the C-4 in the van. It’s behind the bodega on Bainbridge. Locked up tight.” I had my father’s Colt in my waistband, and the other men were strapped with whatever they had. Whatever happened when the neighborhood buttoned up at nightfall…”

It’s the same when we write sales, marketing, business writing, or editorial pieces, or even in verbal conversations like a sales pitch or a teaching presentation. Starting from the beginning, which is probably how we were trained in school, is almost always less compelling than if we fast forward our idea to the really good part—the part we thought we would build to—and start from there.

An amateur thinks that if he does that, there’s nowhere to go; the piece will be brief and over too soon. An amateur frets about length. An author knows that there are always ways to make things worse—to go deeper and increase the pain, the jeopardy, the stakes—so that the glory of the resolution is that much more profound. An author thinks of the reader first. He goes for the gut, knowing that the head will follow.

“We are providing a new service to keep your car spotless at all times. It’s rolling out in NYC and Chicago first, with an app and a website for easy access from any device. The gist is that you pay one low annual fee and provide a window of time when your car is not in use. Our team of bonded professionals picks up your vehicle, has it washed, vacuumed, and micro-detailed, and returns it without any interaction required by you. You never even notice it is gone. It just looks and smells fresh all the time…”

You’ve got a business meeting, or you’re picking up your parents from the airport. The pigeons and the neighbor’s sweetgum tree have smothered your car all night long, dropping bombs on it until it’s a sticky mess. Also, you left that Popeye’s bag under the seat, and it has ripened in the sweltering August heat. Damn, right? Well, that’s one reaction. The other is that little gremlins—our gremlins—detailed your ride before your alarm clock went off, and your Lexus now looks like it’s owned by someone who never eats fried chicken on the BQE…”

Don’t Linger Over Business as Usual

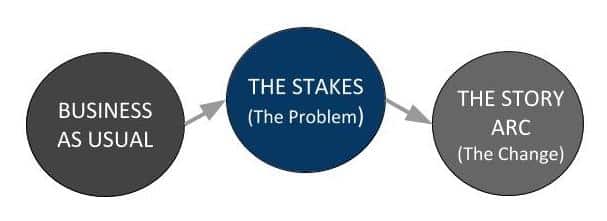

Whether looking at a press pitch or an artist statement, I need to be able to examine the inherent story structure, so I distill it down to the most simplified map of the universal story arc that, to my knowledge, anyone’s ever made. It’s just three parts:

But Business as Usual (BAU) should not be understood as starting all the way at the beginning of the idea. It’s actually the shortest part of the story arc, just a way of introducing the stakes. The stakes are the reason we read stories at all. It’s the problem—the disruption—that engages our feelings, activates our intellects, and ennervates our will to consume content.

Whereas 19th-century storytellers started with the past (“Giles was three years old, growing up in West Baltimore as the son of an accountant and a church pianist, Cedrick and Amanda Peterson…”), 20th- and 21st-century content creators insist on getting to the present as quickly as possible. “A shot rang out in the dark. Giles ran across the street, but it was too late. A sedan sped away, and blood pooled around the head of Amanda Peterson…”

There is a BAU component, and it often comes at the beginning of the story (though it doesn’t have to), but we don’t linger over it for long. Or if we’re going to give it some length, we start with some sign of the stakes, using a technique called “the hook.” We capture the reader’s interest with a taste of the jeopardy inherent in those stakes:

There I was, minding my own business, having a second beer in the corner bar, like I do every Tuesday, when in walks a giant sloth strapped with dynamite. There’d been one or two of these in the news, but never in Ronson, Ohio. So no one said anything at first. He just walked slowly—very slowly—up to the bartender and said…

The story does not start with my first memory from the crib and spend several paragraphs or pages getting us to now. The story starts in the middle, in which a terrorist group of giant sloths is committing a series of atrocities across the US. We also don’t start with how the Slow-footed Underground came to be. We’ll insert a chapter about what went wrong in the evil mastermind’s head later on in the story, but first we want to get the audience to lean forward in their chairs, and that means we introduce the stakes as soon as possible.

A Tale as Old as Time

Story is the universal language. When Noam Chomsky posited his Transformational Grammar in the field of linguistics, insisting there are universal components to communication, he opened the door for us to think about language not just in terms of its particular idiom or didactic content, but also as the total microcosm inherent in the act of all individual communications. When man gathered around the fire at the mouth of the cave, it was not just the light and the community that warded off the dangerous creatures of the dark, it was story itself that produced the salvific warmth we needed to maintain our resolve.

The old-wives’ and hunters’ tales (“big fish stories”) from which the original fairytales came were often dark and full of jeopardy, risk, and caution. We roll our eyes now, but they were the repository of communal wisdom. Far from being irrelevant today, they demonstrate that story taps into our fundamental relationships to other people, our possible place in the world at large, and our core sense of self. Even when we know a story is bullshit, the bar goes hush, the party pulls in close, and we lean forward in the pews as the ritual ingredients of storytelling are invoked.

“I know a guy who says he saw Bigfoot…”

“My sister came home and found her front door open…”

“There was a man who climbed onto his roof during a flood…”

The best communicators—amateurs or authors—are storytellers, even if they’re giving a lecture on the mineral components of soil on Mars. (“The third Mars Rover stopped communicating 20 seconds after landing…”) So when someone asks me to look at a piece of content and give feedback, the very first question in my mind is “Where’s the story?” Where are the stakes in that story, how amplified are they, and how soon do you plug us into those stakes, that disruption, to the problem you propose to solve, or the dilemma you want to illuminate or get me to solve?

Got your attention? Stay tuned. There’s more about storytelling to come. I once knew an artist who said, “I’m not sure I’m trying to do anything important with my art.” To which I said, “If that were true, you wouldn’t get out of bed and put in those long, often thankless hours while everyone you love questions your career choices.” Tell me there’s no powerful story with real stakes, and I won’t believe you.