Professionalism is one of those concepts, like success, that eludes clear definition. An army of consultants, bloggers, and business magazines WILL define it, but we sense they’re being disingenuous, because they will also laud the maverick, outlier, and disruptor who doesn’t fit any such mold. It’s as though “professional” is a tall-poppy concept—encouraging most of us to color between the lines while the gifted people get to tear up the page.

I don’t buy it. And I think not buying it is key to having lives and careers we love. It’s not merely a semantic issue—the word “professional” is placeholder symbolism for demoting ourselves to a measurable good that never amounts to great.

It’s also about other people, and specifically a few other people who prefer to shape our vocational destinies so they can feel assured of a steady stream of reliably compliant labor, even if that’s as outdated as coal furnaces. The industrial period construed the professional, in all but a few cases, as a set of hands, where now what we need at every stage of industry is minds. Professionalism is a continually resurrected vestige that’s past any contemporary relevance to how value is created.

“The era of empty professionalism is dead.”

Dissect the concept of “professionalism,” the way it’s widely construed, and it’s really about fit. Fit is a buzzword issue in hiring departments now. The number of job interviews, for even menial jobs, doubles and triples. “We’re looking for people who are a fit,” they say. The kinds of invasive and presumptuous questions one gets, the psychological profile tests, the inquests into people’s financial data—it all implies a desperate wish for interchangeable workers, “professionals” who are more like the drone army of the Star Wars saga than the diverse, weird, sometimes wooly members of the rebel resistance.

The abomination—the outright heresy against the self—is when we take those desires for sanitized human implements of production and apply them to our lives as independent professionals, as creative people, as breakout talents. There IS something to break out of, and it’s the culture of fit. When a drone dies, we have a moment of silence. When a breakout talent dies, there’s a line down the street in the rain, in the mud. The mourning disrupts the mechanisms of production. Remember the Kennedys? Bow the head for Elvis, the King. Leave the factory levers for MLK.

Yet we do succumb. We’re prone to wonder whenever we talk about our work, “Should I wear the tie?” The originals don’t wonder (Hell no, said Steve Jobs. My collars don’t have a place for ties). We think of a myriad of minute social norms from the corporate assembly line, like an e-mail reply saying “OK, thanks.” despite that forcing another unnecessary task on the other person who dutifully composes, “You’re welcome”. We think, “I’d better do x—it’s professional.” So we hit Reply and write, “Any time.” The professionalism of drones is rooted in the fear of not looking good, because keeping up appearances is the surest form of social control where substantive originality is its antidote.

Professionalism is about superficially meeting an already superficial standard. It’s about the little silk pocket square that is non-absorbent and useless as a hankie and ridiculous as a puddle cover. It’s about the trappings of our belief in a social hierarchy without the hope of a meritocracy.

And yet, that which has no substance cannot hold. We see it in the news out of DC every day. That which is a shell crumples again and again, no matter how often it momentarily inflates, like a pufferfish trying to project ferocity and gravitas. Play-Doh is Play-Doh. It only stands up when we prop it up.

Substance is the real disruptor. A subway ad from Oscar or Spotify or Seamless isn’t “professional”. They swear. They use risqué scenes (like a man staring into his underpants in an Oscar ad). They use political humor (like Spotify teasing Sean Spicer). They outrageously slam people who aren’t their current audience (like the Seamless posters in NYC making fun of Jersey and Westchester). They’re at once aspirational and real-world authentic, which is why those brands are yanking business away from the entrenched captains of industries that are normally sanitary, sexless, and uncontroversial – i.e. “professional”. A podcast that starts out in a garage studio now trounces print media and network TV, even though the host isn’t wearing a suit or studio makeup. An artist in a purple scarf with an earring and a neck tattoo bumps into a Wall Street banker on the subway, because they both live on the same block. The era of empty professionalism is dead.

So is there still meaning in the word itself? Maybe. Personally I couldn’t care less. Words are expendable; truth is not. Words often need to be hacked to keep up with the truth. For example, Steven Pressfield says. “A professional is someone who shows up”—for his life, his commitments, and his goals. A professional puts in the energy, doesn’t relent, and doesn’t quit when it’s hard. I’ve made an empirical study of businesses that “make it”—meaning they achieve the goals they set out when they started versus those that fail. The ones that made it didn’t quit. At some point, they didn’t throw in the towel when any rational person would have. I think the rest, the ones that relented, will never know what they almost achieved.

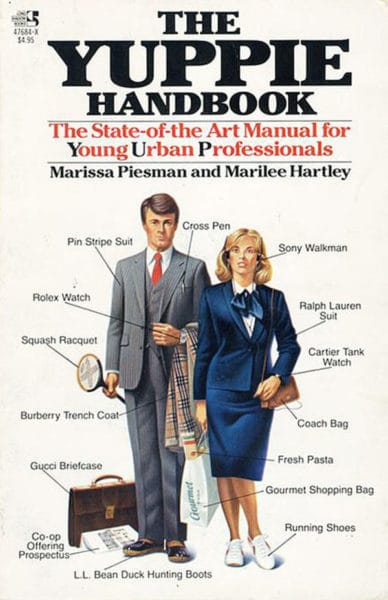

Remember the old Yuppie poster from the 1980s? It was from the cover of The Yuppie Handbook and listed the ingredients of a Yuppie: squash racket, Cross pen… There was one for nerds, too—pocket protector, tape on the glasses—courtesy of National Lampoon. Professionalism isn’t like either of those. It’s not a list of ingredients for fit. You can’t dress for it or go in disguise.

When someone delivers value consistently, at a high level, focusing on objectives and outcomes, I think that’s a professional—whether it’s for their own business or someone else’s.

But isn’t that just a list of other ingredients? No, because you can’t get a generic version of that stuff. Anyone with the cash can buy a power suit; anyone can avoid racy words and edgy branding. So often that type of “professionalism” is a list of don’ts. But kicking ass is always specific. It’s always the way YOU kick ass. It’s irreplaceable, non-interchangeable, and cannot be measured on some J. Evans Pritchard scale of professionalism. The professionalism that disrupts is always our own unique recipe.

Which would you rather be? The David Bowie, Ernest Hemingway, or Winston Churchill of your profession? Or the buttoned up, clean-pressed… wait… we can’t think of any names. That’s right. No one remembers “professionals” built according to the factory model, with its cattle call for generic, processed types. Most of us would rather meet originals.

Thought provoking, Daniel. It’s about what people do, day in and day out, and when no one is looking, that also matters. People can look the part and say the right things when the spotlight is on…but what do they do? What value are they adding? What do they deliver?