Joyce Creiger is an art-world polymath. As a leading art consultant, she’s placed work in all kinds of environments, from commercial spaces and hospitality businesses, to healthcare facilities and government centers. A former gallery owner herself, Joyce currently owns an art-rental business, as well as an art-marketing company that’s teaming up with a huge online retailer (more on this below). As if all of that were not enough, she also produces a local cable TV show in Boston and is an artist herself.

In this Q&A with CHF Editorial Director Sofia Perez, Joyce talks about the changes she’s witnessed over more than four decades in the industry, and describes the process of matching artwork to client.

You have worn many different professional hats in the art world. Give us a brief overview of your current work.

My art-consulting firm, Creiger Group Art Services, was one of the very first (if not the first) art-consulting firms in the country. We’ve been around for more than 45 years, so I’ve been doing this for a long time. A number of years ago, I formed a company called Boston Art Rentals. We own 3,000 works of art that we rent to stagers, corporations, and others.

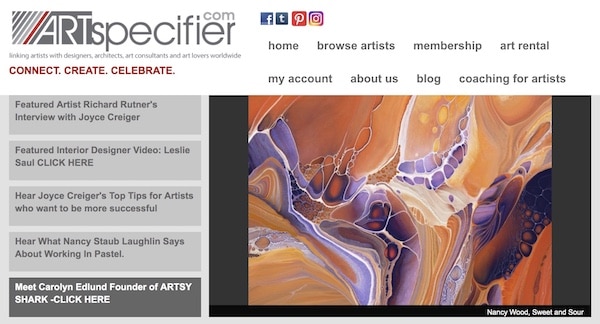

About ten years ago, I started a marketing company called ArtSpecifier, a members-only website that accepts no more than 100 artists at any given time. We help promote their websites, through newsletters (usually two per month), and scrolling images on our site that feature ten different artists each week. We also have a blog and a Facebook page that go along with it.

Most recently, ArtSpecifier has partnered with Wayfair’s high-end division, called Perigold, which is just about a year old. It’s geared toward high-net-worth individuals who have two homes, which are often in areas that don’t have easy access to galleries. The company is hoping these folks will shop online, and we’re going to be providing them with original works from our ArtSpecifier members.

I also run a local cable TV show called Art Link, which features interviews with ArtSpecifier members and others, including architects, designers, and stagers—anybody that’s involved in actually making or using art. Those interviews are featured on the ArtSpecifier website, as well as on our YouTube channel.

Finally, I have my own studio and do a lot of commission work for clients. I’ve been doing that for what seems like a hundred years.

As an art consultant, you’re kind of a matchmaker. Are your clients clear about the kind of art they like, or do you have to help them figure it out?

Let’s take an example. Recently, we were approached by a development company that was taking down an escalator outside, in what was a very prominent space in Boston. They also needed artwork for four of their lobbies, so it involved tackling two different projects.

For the lobby areas, we talked first about buying, but then they decided that they wanted to rent the art, so we gave them many different options. Eventually, they bought artwork for each of the different lobbies, and we helped them develop their budget, sourced the individual pieces, and installed them. Then we had to make recommendations for the exterior piece, which ended up being a metal sculpture by Shelley Perriott, who’s an ArtSpecifier member. She developed an amazing piece that will sit on a pedestal in a plaza, lit from below. The client didn’t have a huge budget—it was around $25,000, including the lighting.

We’ve worked on projects as far away as Saudi Arabia, where we did a hospital. We had to work with the Saudi government, which meant dealing with their parameters about what they do and don’t use in artworks. You can’t have anything that is representational, so we had to be very careful. In fact, before we went on the trip, we went to a consultant to learn how I had to work in that country, particularly as a woman.

So, each case is different. It’s a lot of handholding, a lot of giving the client information, and then helping them make decisions.

If a potential client tells you they want a large-scale bronze sculpture, for example, are you going out and looking for new artists, or only pulling from your ArtSpecifier member pool?

The former. In fact, Shelley was not a member when we started working together. I’m always in search of new artists. I’m cruising Facebook, looking at Instagram and Linkedin, and searching out in the world, at galleries. I am looking for new artists every single day. When I found Shelley’s work, I fell in love with it, and we developed a wonderful relationship, so she decided to become a member.

ArtSpecifier is very different than most websites where artists are promoted or where their work is sold. We don’t sell anything on there. That’s why I formed the relationship with Perigold because it gives these artists a platform to sell their work, whereas with ArtSpecifier, we just market their work and coach them. I work with them one on one if they need it. If they want help putting together an RFP for a project, they call me. That’s different from most platforms—like Fine Art America or any of the other websites.

Do you commission works, or are you looking for pieces that are completed and that you’ve already seen (in person or through social media)?

All of the above. If an artist has an available piece that works for a particular space, I would definitely go there first. If they don’t, and there’s a specific area where we’re looking for a piece and we can’t find an existing one, then we might commission it.

Recently, I worked on a hotel, and almost everything in it is commissioned because it’s very unique to the specific location, and they want artists from a specific area. I’m also doing a senior-living project, which has some commissioned art, and a lot of the work that I’m sourcing is from what’s already available.

We did the Luxor in Las Vegas. When they came to us, they said, “We need artwork that looks like it just got dug up from King Tut’s tomb.” We had to do research with an Egyptologist, but we created 40 objects that were specific to what was dug up in King Tut’s tomb.

That’s probably what’s kept me in this business for 45 years. Each project is new and exciting, and it gives me a chance to be creative and come up with solutions that I didn’t have to create for a prior project. It’s constant stimulation and the enjoyment of putting together something unique.

When a client is commissioning something, it sounds like communication is a big priority.

To ensure that there’s never a problem, we always do in-progress photographs. That way the end-user gets to see things as they progress. If the work is different from what they had anticipated, we can catch that early on. Everything is spelled out in the contract—the size of the piece, the colors, where it’s going to go, what kind of lighting there is, what the base is going to look like—and the client approves it every step of the way. I have never done a project where anybody has ever been unhappy because I pay a lot of attention to detail. That’s critical.

As someone in the position of finding new work, you really get an overhead view of the market. What are some of the big trends you’re seeing?

To answer that question, I have to give you a little history. I’ve always thought of myself as a bit of a visionary. I’m not the perfect middleperson—I’m a great starter and a terrific ender, which is why I’ve always had assistants that I’ve trained who work with me on the middle piece of it. I like the excitement of finding the client, of bringing them the artist, and I love to seal it up.

“The biggest mistake artists make is trying to be all things to all people.”

I’ve come up with things that have failed in the past. Back in 1985, I started the first interactive laser-video-disk art catalog. This was before the Internet. I took Sony’s hardware—which was used to train fighter pilots to fly planes on a computer—and married it with the Library of Congress’ software. We developed a way of finding information on a disk, and there were 12 galleries across the country that used our standalone system. Artists could put their images on the disk, and people could go on the computer and say, “I want to find a painting of an ocean in California under $10,000.” Which is what you can do today in a few keystrokes online.

Ultimately, the business failed because it was done with analog technology before digital technology moved to the forefront, and my investor pulled out. Although it failed, it was a big learning experience for me. In 1990, I did the first digital show in my gallery on Newbury Street, where I was highly criticized by all of my colleagues because I was showing work that was created on a computer. People thought that was a travesty. “How could you have a gallery on Newbury Street, and not show paintings and sculpture and original works of art?” But I had people in the show like Jonathan Borofsky and David Hockney. They were experimenting with the computer and digital images. The show ran for two months, and we showed 40 different artists.

Today, I’m getting calls from people who want to recreate that show because it was so pivotal. What I’m saying is that when Perigold came to me, I had colleagues who said, “Are you out of your mind? You are going to go to a company that advertises on TV and sells furniture, and you’re going to put original art there?” My response? Wake up! The Internet is where hundreds of millions of dollars worth of art is being sold.

So to answer your question, I believe that the Internet is going to be the game-changer for artists. They have an opportunity. They can have their own website and do their own marketing to bring their work to the forefront—gathering their own audience and their own collectors. An artist who doesn’t have a massive online presence today and is just waiting for their gallery to make a living is crazy.

Artists need more than one way to earn money from their art.

Yes, I urge every artist to develop multiple streams of income. I’ve never believed in counting on one source. If you lose that one client, you’re screwed. You have to think about how to generate money from sales of your artwork, from licensing, from selling other things on your website, and on and on. Maybe you’re promoting other artists—whatever it is. It’s nice when I get a check from ArtSpecifier, and another check from the Creiger Group, and a third check from the rental business. All of that helps to support me and support what I do.

And artists shouldn’t be afraid to do giclée prints and hand-embellished giclées. You can do an original piece that’s beautiful, and sell it at top-of-the-line prices, but also have an ancillary product line where you can make additional money. A lot of my artists say to me, “I don’t want to do digital prints because it’s going to devalue my work.” No, it’s not. It’s going to increase the value of your original work. And it’s going to give you additional income, from being able to sell something at a little bit lower price so that you have a wider audience appreciating your work.

What does an artist need to know before approaching an art consultant like you?

I think the biggest mistake artists make is trying to be all things to all people. It’s very hard to do that. You’ve got to run a business like others do. No one does every aspect of it. They farm things out, use interns, hire assistants. There’s no reason an artist has to spend time priming a canvas. Anybody can do that. You get people to help you so that you can maximize your time and your talent.

If they want to run a business, they have to run it like a business. Get an accountant or a bookkeeper. Have a system for keeping track of the artwork. And the single most important thing they need to do is sign their work. Do you know how many times I’ve gotten a phone call from an auction house asking me, “Can you look at this painting and tell me who did it?” There’s no signature on the front or the back, so how would you know?

When you’re creating your website, please put your phone number on there. Nothing is more frustrating for an art consultant or designer than having to fill out a form and wait for a response. They’re working on a project, and want an answer instantly. If they can’t call the artist and reach them, they get frustrated, and they often don’t bother to pursue it. It’s that one on one that matters. That designer has got a deadline. She’s got four projects going, and she’s got to meet her client tonight. She wants an answer. And if she can’t reach the artist, she’ll move on to the next one.

When you started ArtSpecifier, it was the first online platform to link artists with designers and consultants. How has that work evolved?

Right now, there are so many platforms that flood the market. I keep it really small. I can manage 100 artists, not 10,000. With the latter number, you’d have to just throw them up there and see what sticks. Artists need to be focused on what they want to accomplish and go for a platform that can help them achieve that.

I partnered with Perigold because I felt that the artists on my site needed more. We were marketing their work, but they needed the ability to sell it, too. We were driving business to their website but they didn’t necessarily know where that business was coming from, because there was no direct link. We just put their name and image out there, and anybody could find them through Google. As a member of ArtSpecifier, they now sign a contract with us, provide us with a certificate of insurance so that there’s a liability policy, and then they can be added to Perigold, where I can track their sales. Everything gets shipped to me so that I can make sure it’s in good shape, and then Perigold picks up the artwork from me and ships it to the client.

On ArtSpecifier, you not only connect people, but you also present exhibitions and projects. Tell us about how you foster a creative community.

I will often meet with ArtSpecifier members, and we’ll bounce off different ideas. I had lunch with one of my artist friends a couple of days ago, and I’ve kind of nurtured him. He’s a photographer, and he’s also been doing video and portraits. When we talked, he told me that what he really wants is for his fine-art photography to be recognized. He wants to be in a gallery and get more recognition for his work, rather than just doing a one-off project.

I suggested that he drop some of the other things and really focus on the fine-art photography. Right now, he feels so much better about his career than he has in the past. He feels more satisfaction and sees more progress. He’s been getting accepted into exhibitions. So it’s that one-on-one consultation with them, feeling out what they want in their gut and trying to help them achieve that.

Ultimately, it’s all about listening. If you sit down and ask a question, and you listen to the answer without injecting your thoughts or directing the conversation, you get to hear what’s really on someone’s mind. And when you can mirror that back and tell them what they’ve just said, all of a sudden it’s an “a-ha moment.”

Tell us about your art-rental business. Are you renting out reproductions, originals, or both?

All of the above. I’ve been buying art since I was 16, and when I had my gallery, I always bought one or two pieces from every show. That was my commitment to the artist. So the 3,000 works I rent out are a combination of pieces that I’ve bought and work that I’ve traded for. Sometimes an ArtSpecifier member will say to me, “Look, I want to be on your site so badly, but I don’t have the money,” so I offer to trade. “Let me pick a piece of art and whatever the value is, I’ll give you that many years as a member.”

“You shouldn’t hold yourself up as so exclusive that you’ll only show your art in a major gallery, because galleries aren’t doing very much business anymore.”

I also work with companies who have artwork and want new art, but they don’t know what to do with the art they already have, so I say, “Give that to me, and I’ll credit you X amount of dollars towards the new work.” I’ve amassed this huge inventory of everything from sculpture and drawings, to prints and giclées. Other people who were going out of business have called me up to say, “You know I have 25 pieces. I’ll give them to you for $500,” and I’d buy them.

Since I’ve acquired all of this art, it’s just easy for me to rent it. A client will call—a stager, for example—and say, “Can you come on Thursday? I’m staging a house, and I need about 20 pieces for it.” I charge them $35 a month for each piece that’s smaller than 40 inches. If it’s larger, the price runs anywhere from $50 to $100, depending on how big it is. For me, it’s not so much about the value of the work as it is about how easy it is to handle it and get it where it needs to go. If I have to include a big piece, that means I have to rent a van so it’s going to cost them more money.

Because I only charge $35, I only use work I own. (If I were to split that with an artist, it wouldn’t be worth it for either of us.) But if an artist wants to rent their own artwork, they can use that same formula.

There are also companies that do rentals and that will put up a little plaque for the artist, to give them some play. For artists, the advantage of renting might be that they could ultimately get a sale from it. We do often sell work from our rental program to homeowners if, for example, they are buying the home. They walk in and see how beautiful the piece looks, and they’ll call up to say, “You had artwork in here, and now it’s gone, but we loved the pieces that were in the living room and bedroom. Can we buy them?” Of course, the answer is always yes. Why not?

An artist might even get a new commission from the exposure of having their art in that space.

It certainly can’t hurt. I’m a firm believer in putting art where people will see it. I did a show of my own artwork in Chico’s—you know, the store in the mall. I sold work from that. I believe in getting it out there wherever you can. If a restaurant wants you to put up your artwork, you can make a sale. You never know.

Most recently, I was in a little coffee shop, and there was artwork on display that I really liked. I asked the owner whose artwork it was. His reply? “It’s my husband’s.” So I called up the husband and after 20 minutes of conversation, I ended up renting him my studio because I was leaving that space to move to a new studio. He never thought he needed a studio—he was working out of his bedroom—and now he is the happiest guy, because he has his own workspace. And why? Because he hung his artwork up in his husband’s coffee shop. You shouldn’t hold yourself up as so exclusive that you’ll only show your art in a major gallery, because galleries aren’t doing very much business anymore.

So much of your work is curation. How do you differentiate what you do from the stream of art content on Twitter and Instagram?

When I first started ArtSpecifier, I turned away at least 30% of the artists who applied because I held it to a very high standard. There needed to be a lot of third-party validation, and I wanted to make sure that their resumes were really good. I was looking at credentials more than I was really looking at the art—and I can tell you now that I was wrong.

It was my assistant Cathy who called me on it. “You’re making a mistake,” she said. When I asked her what she meant, she replied, “That piece of art is really pretty, and people would love to buy it. Why are you not including it?” My response was that there’s nothing unique about it; the artist hasn’t done anything different than anybody else. “Yes, but what she’s done has been done really well. It’s really beautiful and people will want that in their home.” So I relented.

Little by little, I found myself being less critical, and trying to open myself up more to what the public might want, as opposed to what an art historian might feel was acceptable. That was hard for me, because I come from the background of being a curator, where I want to see a unique use of the medium, and am looking for art that I would’ve shown in my gallery. But with the Internet, and a buying public as vast as it is, I realized that I needed to appeal to a broader audience, so I found myself accepting more artists on ArtSpecifier. I felt that I had a responsibility to show a broader spectrum of work, so I went a bit more commercial.

Sounds like you’re letting the market decide. If someone wants to buy it, why not?

Exactly. And now with the partnership with Perigold, I’m happy I did that, because they’re going to be looking for all kinds of work. I still have people on ArtSpecifier who are doing very unique things—we have one couple that’s doing amazing videos that belong in the Venice Biennale—and next to it you might find a person who does still lifes that the Bienniale would never take, but it might end up in a museum somewhere because it’s beautifully done.

How does being an artist yourself—and one who’s run a gallery—shape what you’re doing today?

When you run a gallery, your obligation is to your group of artists. You have to find them work, and you’re responsible for their income. They’ve signed an exclusive with you, so you have to make sure they make a living. If you’re an art consultant, it’s very different. Your client—the buyer—is your responsibility. It’s the client that hires you and expects you to bring them the best of what’s out there to meets their needs, both artistically and budget-wise. Your responsibility is very different in each case.

In running ArtSpecifier, I feel like I have two responsibilities: 1) to bring the best artists I can to the people who are coming to our site looking for them, and 2) to feature the artists and give them the best possible promotion.

I’ve always advocated for artists, whether I was running a gallery, negotiating for a big-box store, or putting their work on ArtSpecifier, because I’m an artist at heart. I understand where they’re coming from.