How do you develop a story about your artwork, and communicate that story to the public? CHF’s Marketing Director Daniel DiGriz shares storytelling tools that will strengthen your brand and, in turn, help frame your art as relatable and necessary. (This is part two of a three-part series. Read part one here.)

When talking about art fairs, you tell us to get out of the booth and get the audience involved, but I may not know which specific activities are going to support my brand story. Are these activities gimmicks to get attention and be memorable, or do they serve another purpose?

Gimmicks are memorable, but they actually distract from your brand story. They are short-lived. So the choice of activities goes beyond simply telling. Stories are not just told, they’re demonstrated. Stories are immersive and interactive. The growth of virtual reality and 3D film shows the prevalence of multimedia. These days, we’re all talking to our audio devices—Google Home and Alexa—-which suggests that people have a desire for storytelling that reaches out and touches them, in a more immersive and involved way.

What you’re asking is: “How do I figure out what I should be doing? Is it a gimmick?” No, it’s not a gimmick. When people walk away from your immersive storytelling, which goes beyond just the telling, you want the story to actually stick, instead of just the fact that you did this cool gimmick that’s associated with your name. There is no one-size-fits-all.

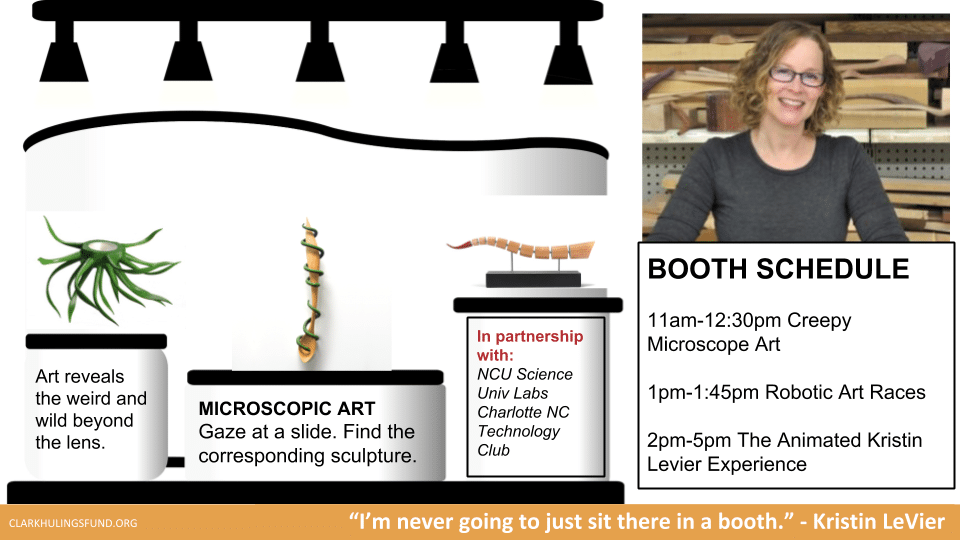

A good example is CHF Business Accelerator Fellow Kristin LeVier. In response to her art, Kristin, who is a university-trained microbiologist, hears “We’re not all microbiologists.” Her work shows us the wild realm that’s too small for us to see. How is Kristin going to tell her brand story when the focus is magnifying what’s under the microscope? Her art is the answer, but if she simply shows us a snaky, spider-looking creature, we don’t know what that’s telling us. We don’t know the story. All we know is that there are spider-looking creatures. What does that mean?

It doesn’t matter if we race them down the aisle at the art show with no other narrative, or if we just show pictures of the specimens or the art itself, because the art is never a substitute for the story. The portfolio is not the answer. Photography is so 1993! Simply offering a photograph-only portfolio of your art, or inviting people to exhibits so that they can see the originals denies the human need to be immersed in the story.

Gimmicks are memorable, but they actually distract from your brand story.

So what we’re saying to Kristin is, “Don’t just have a gimmicky event, at which you’re racing robotic spiders down the aisle. Instead, pair that with microscopes and a narrative, or pair it with an animated video about the characters that your art embodies.” Because each one of those living things that she makes into art are living forms—they’re characters. So Kristin can combine immersive experiences with a narrative that plugs us in, that connects the dots for us.

A Fictional Example

The Audience Demands Immersion

As for figuring out what the story is? There’s no substitute for taking a deep dive and asking, “Why does anybody care?” I think there’s a built-in assumption in visual art that we should all care about art just because it’s art. We should care about art because it’s inherently good. We should care about opera and ballet, too. Well, that myth needs to be exploded. We don’t automatically care about these things. Very often, these things are stuck in a storytelling method that’s from the 16th century, and that’s not the way we tell stories anymore. We don’t have the patience, and we demand immersion.

You’ve mentioned that the story has to solve a problem—how do I know what problem resonates with my audience?

While it’s correct to say, “Storytelling has to solve a problem,” it’s more accurate to say that, “All stories do solve problems.” It’s not a story unless you’re solving a problem. So for instance, at the beginning of every story there’s a contract made with the audience—that you’re going to introduce a problem, and it’s going to pay off with a solution, even if the solution is a tragedy. For example, “This guy was a drunk and a womanizer, and he needs to overcome that in order to be heroic and save the world from the Nazis.” I’m thinking of Casablanca.

The question I suggest visual artists ask themselves is, “What is the basis for the connection you’re trying to establish with other people?”

Right up until the end, we don’t know if Rick is going to change or not, but we do know something is going to happen. The problem might be resolved because he doesn’t change, and therefore the resistance has to fight harder, and the Nazis may not be overcome. So the solution we’re given is: “Stop hoping for heroes.” Another solution is that he does change his mind. He tells Ilsa to get on the plane, goes against his motto, and sticks his neck out for everybody, and becomes a hero in the end. That solves the problem, in that sometimes you have to set aside your personal desires and be a hero, even if you’re just an ordinary man.

It Starts With Your Why

So, how do I identify the problem that my art solves? I would say that there is no substitute for asking yourself why you get up in the morning and do what you do. Many people provide placeholders answers. “I don’t know—I just feel it.” Or, “I just want to make something that represents the world I want to live in.” That isn’t a dead end or a non-answer; it’s a placeholder. In order to be effective at creating a brand around the art, the duty of the artist is to go deeper than that and say, “All right, but WHY do I feel this? Why do I want to make this?” They succeed when it’s no longer just about them, but when it’s about other people.

The number one premise I hear (which is a dead end) is, “I don’t make art for anybody else, I just make it for myself.” The reason we know that that’s not true is because you are trying to sell it. You are making it with the knowledge that you’re going to sell it, and you want it to hang in a gallery or a museum. You do hope for collectors. You don’t make the art and leave it all in your living room until you have 300 pieces and nowhere to feed your cat anymore. Instead, you make art to get it out into the world. If you’re unwilling to do the hard work of figuring out what’s in it for the other guy, it will feel like a dead end.

Find Where You Plug In

You need to figure out what other people get out of your art, and what connection you want to make with them. The question I suggest that visual artists ask themselves is, “What is the basis for the connection you’re trying to establish with other people?”

The only time I’ve seen an artist utterly fail at this is when the person is terrified of discovering the answer to that question, afraid of finding out what connection they want to have with other people. Usually, that comes up because the artist has created a barrier of fear, depersonalization, or something along those lines. Most artists believe that human connection is possible, and we want to connect with other people around something deeper, the things that we as human beings all share.

I am 14 paintings into a portrait series and find I can make the painting better when I know what emotion I’m trying to show in the portrait. That parallels your final question as to “What is the basis for the connection ….”

Wonderful and meaningful insight. I look forward to diving deeper into my story telling.